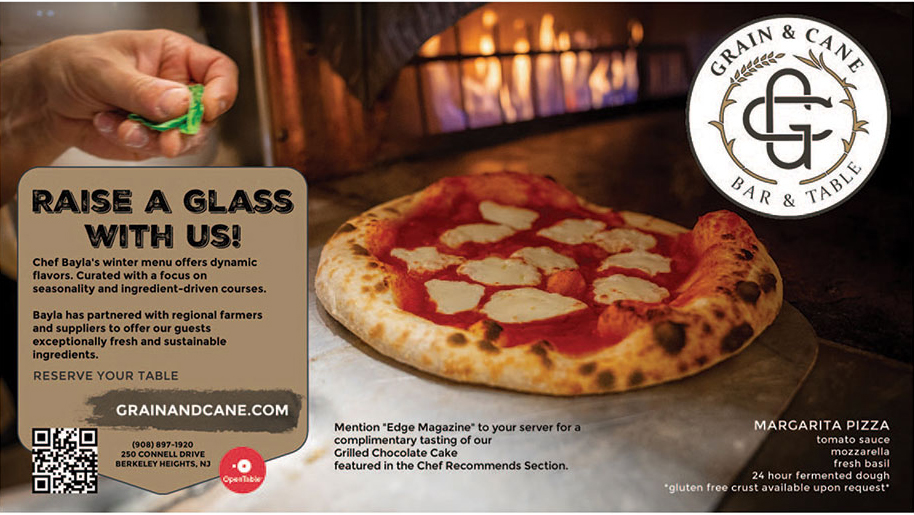

Grain & Cane Bar and Table • Grilled Chocolate Cake

Grain & Cane Bar and Table • Grilled Chocolate Cake

250 Connell Drive • BERKELEY HEIGHTS

(908) 897-1920 • grainandcane.com

A chocolate lovers dream – our Grilled Chocolate Cake is made with moist devils food cake, layered with chocolate fudge and iced with chocolate buttercream. Grilled to order, this process creates a crunchy caramelization that adds a unique texture to this crowd favorite.

The Thirsty Turtle • Pork Tenderloin Special

1-7 South Avenue W. • CRANFORD

(908) 324-4140 • thirstyturtle.com

Our food specials amaze! I work tirelessly to bring you the best weekly meat, fish and pasta specials. Follow us on social media to get all of the most current updates!

The Famished Frog • Mango Guac

The Famished Frog • Mango Guac

18 Washington Street • MORRISTOWN

(973) 540-9601 • famishedfrog.com

Our refreshing Mango Guac is sure to bring the taste of the Southwest to Morristown. — Chef Ken Raymond

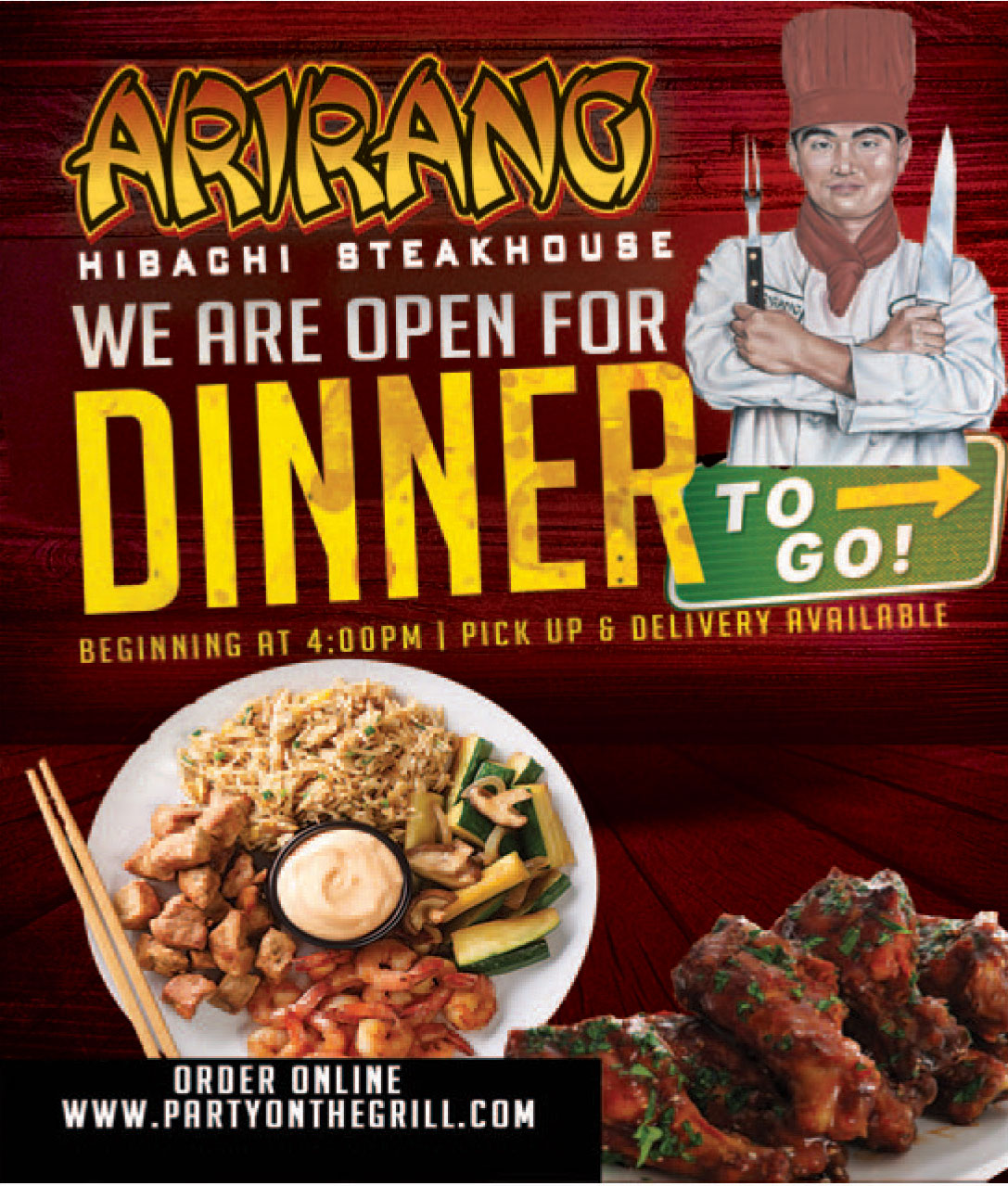

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Wasabi Crusted Filet Mignon

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Wasabi Crusted Filet Mignon

1230 Route 22 West • MOUNTAINSIDE

(908) 518-9733 • partyonthegrill.com

8 oz. filet mignon served with gingered spinach, shitake mushrooms and tempura onion ring.

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Japanese Tacos

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Japanese Tacos

986 Route 9 South • PARLIN

(732) 525-3551 • partyonthegrill.com

Crispy wonton taco shell, Asian slaw, topped with spicy mayo, togarashi and our famous teriyaki sauce.

PAR440 • Chilean Sea Bass

PAR440 • Chilean Sea Bass

440 Parsonage Hill Road • SHORT HILLS

(973) 467-8882 • par440.com

It’s pan seared and served over corn, black beans, peppers, celery, pineapple, with a corn coulis sauce.

Ursino Steakhouse & Tavern • House Carved 16oz New York Strip Steak

Ursino Steakhouse & Tavern • House Carved 16oz New York Strip Steak

1075 Morris Avenue • UNION

(908) 977-9699 • ursinosteakhouse.com

Be it a sizzling filet in the steakhouse or our signature burger in the tavern upstairs, Ursino is sure to please the most selective palates. Our carefully composed menus feature fresh, seasonal ingredients and reflect the passion we put into each and every meal we serve.

Welcome Back!

The restaurants featured in this section are open for business and are serving customers in compliance with state regulations. Many created special items ideal for take-out and delivery and have kept them on the menu—we encourage you to visit them online.

Do you have a story about a favorite restaurant going the extra mile during the pandemic? Post it on our Facebook page and we’ll make sure to share it with our readers!

EDGE is not responsible for any typos, misprints or information in regard to these listings. All information was supplied by the restaurants that participated and any questions or concerns should be directed to them.

Pope Julius II and Renaissance sculptor Michelangelo were at odds, but the Pope insisted he paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. No painter, I, the artist balked. Nonetheless, it took him four years, mostly lying supine on scaffolding.

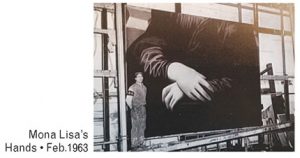

Under the auspices of the O’Mealia Outdoor Advertising Company, Jersey City-born artist Louis N. Riccio eagerly agreed to paint a 15′ by 25′ billboard in Secaucus to laud the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition in 1963. It took him four days, eight hours per day, to paint an incredible likeness of da Vinci’s most celebrated work. At the time, Riccio was 29. His career continued to make history.

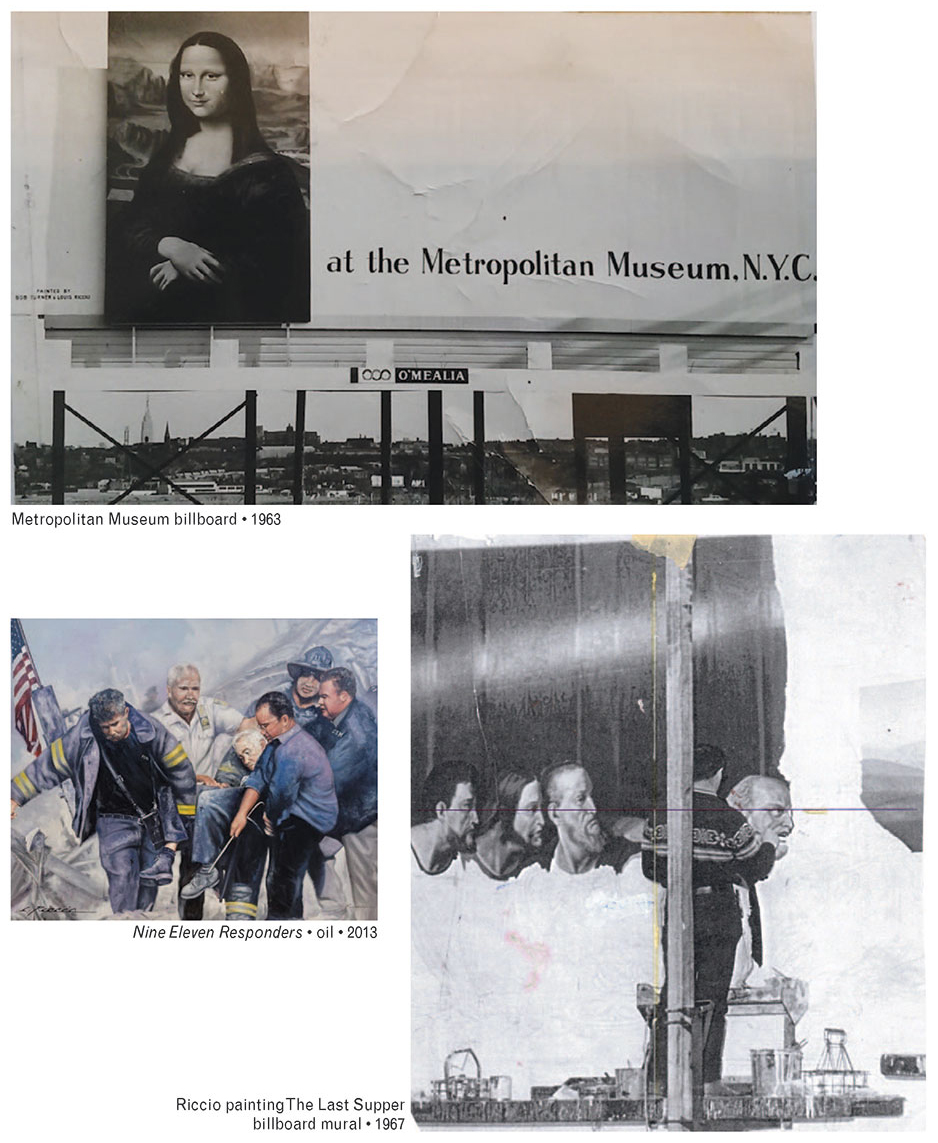

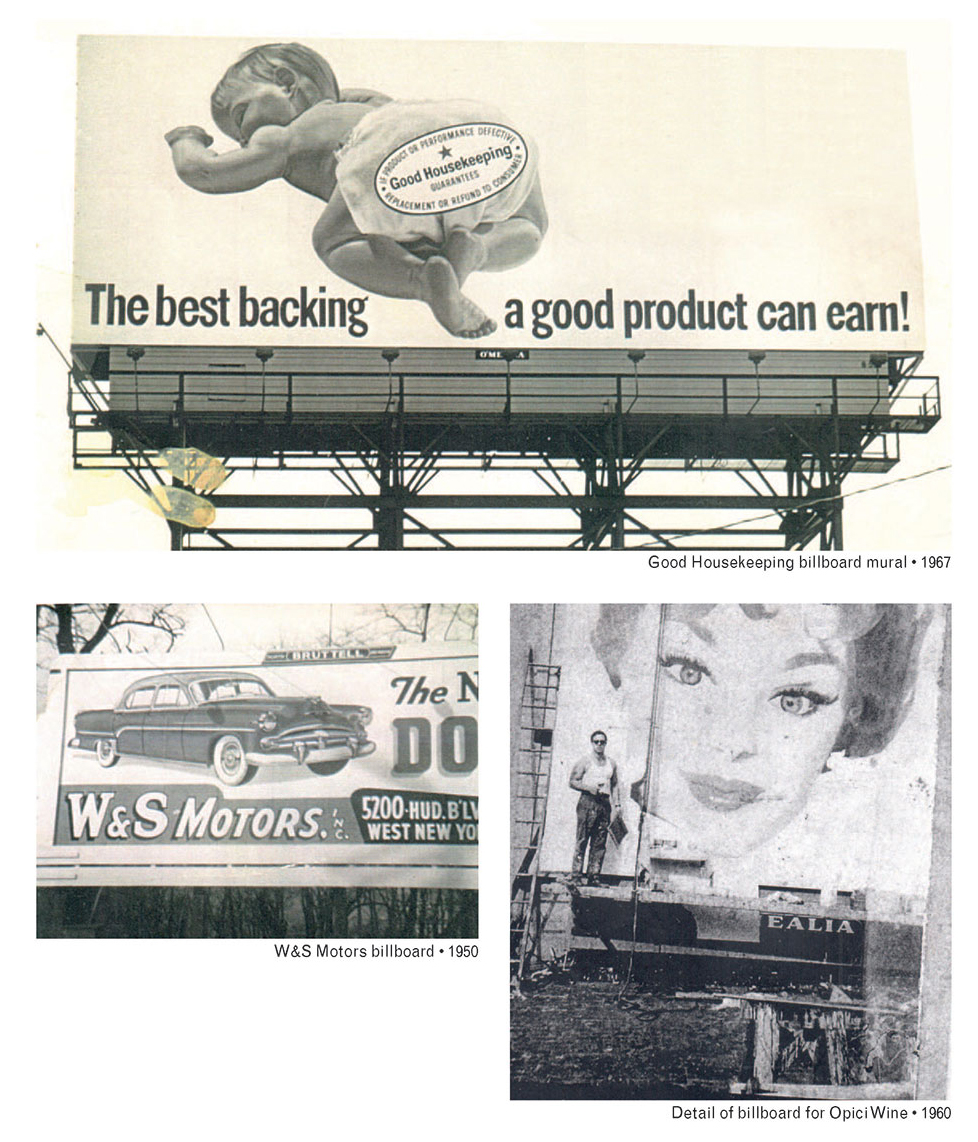

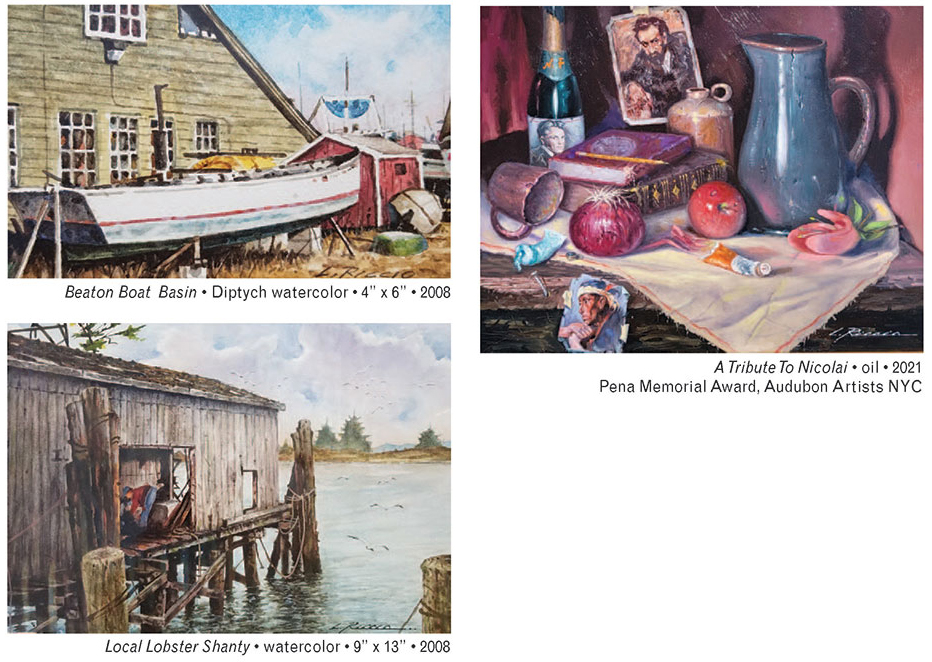

See the billboards along the roads? Art? Not like the ones by representational artist Louis Riccio of Brick Township. He spent 20 years on scaffolding as he hand-painted huge billboards. Working in tempera and other mediums, he maximized all he learned from legendary New Jersey artist John Grabach—in addition to three years of art school in New York City and six years at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts. He painted da Vinci’s The Last Supper in two and a half months. “I follow the traditions and work ethics of the old masters,” says Riccio, 90, who served in the Korean War as a medic. Given his career as an award-winning painter, Riccio’s landscapes, portraits and still lifes will never be taken from sight as his billboards were long ago.

See the billboards along the roads? Art? Not like the ones by representational artist Louis Riccio of Brick Township. He spent 20 years on scaffolding as he hand-painted huge billboards. Working in tempera and other mediums, he maximized all he learned from legendary New Jersey artist John Grabach—in addition to three years of art school in New York City and six years at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts. He painted da Vinci’s The Last Supper in two and a half months. “I follow the traditions and work ethics of the old masters,” says Riccio, 90, who served in the Korean War as a medic. Given his career as an award-winning painter, Riccio’s landscapes, portraits and still lifes will never be taken from sight as his billboards were long ago.

See the billboards along the roads? Art? Not like the ones by representational artist Louis Riccio of Brick Township. He spent 20 years on scaffolding as he hand-painted huge billboards. Working in tempera and other mediums, he maximized all he learned from legendary New Jersey artist John Grabach—in addition to three years of art school in New York City and six years at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts. He painted da Vinci’s The Last Supper in two and a half months. “I follow the traditions and work ethics of the old masters,” says Riccio, 90, who served in the Korean War as a medic. Given his career as an award-winning painter, Riccio’s landscapes, portraits and still lifes will never be taken from sight as his billboards were long ago.

A kidney transplant was a no-brainer for Khalil Bell… he just had to wrap his mind around it.

A little more than five years ago, Khalil Bell was at a crossroads in his life. Born with one non-working kidney, and the other functional but deformed, he was looking at a condition that was irreversible, knowing he would have some difficult choices ahead. Bell had to begin a dialysis regimen at 30 years old—a good 20 years earlier than the majority of patients with kidney disease. That made him an ideal candidate for a kidney transplant.

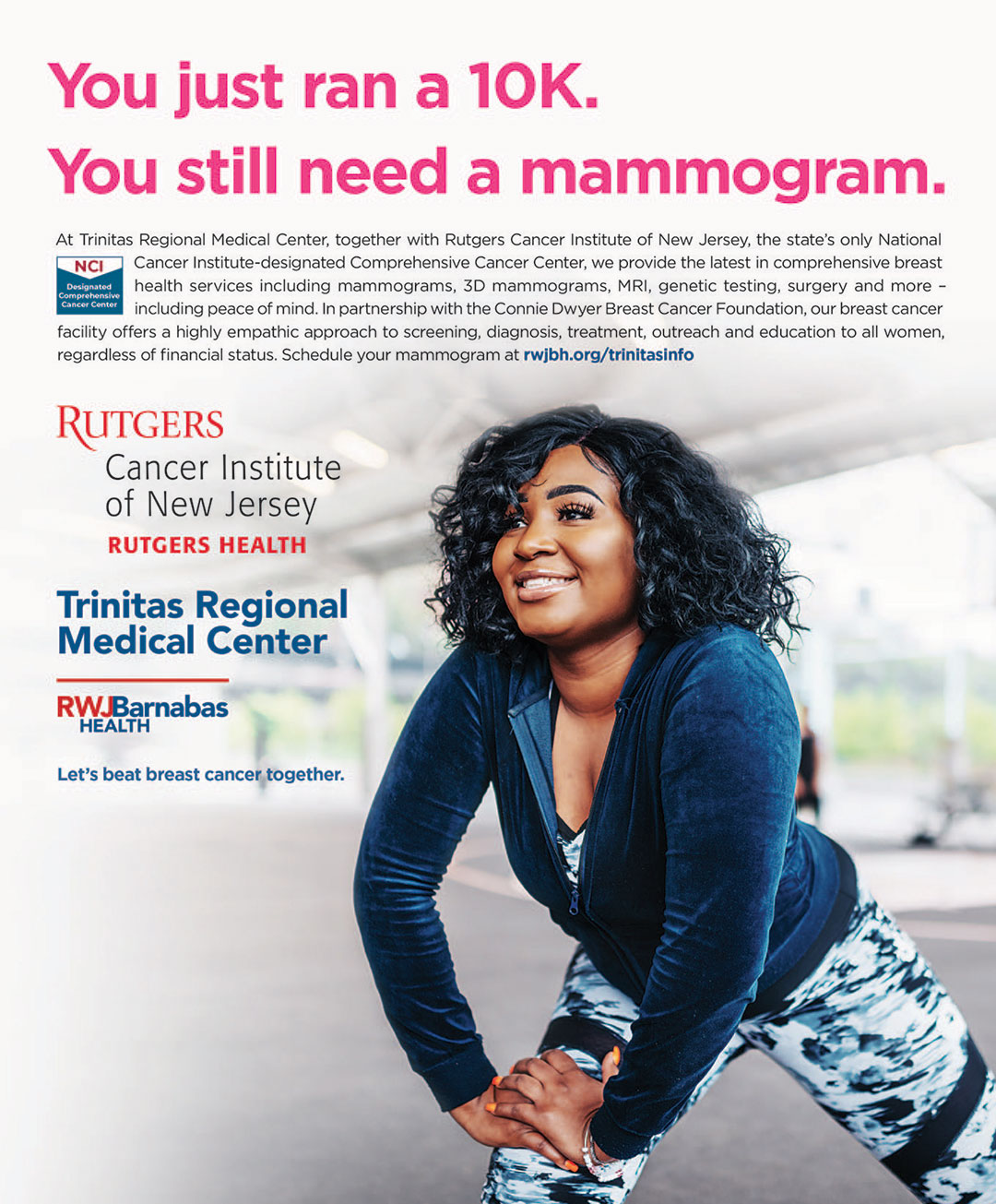

Trinitas Regional Medical Center

But for seven years he put it off.

The issue for Bell was his weight. He tipped the scales at well over 300 pounds and was told the procedure would not be safe until he had dropped 100 or so. Bell’s doctors at Trinitas put him on a strict dietary program, but he wasn’t responding as well as they’d hoped. For a time, he got used to the regimen at Trinitas’ Linden Dialysis Clinic, which, because of his weight, took five hours a visit instead of the typical three-and-a-half for other patients. Ruby Codjoe, Director of Renal Services at Trinitas (right), could see Bell was becoming increasingly frustrated. These were years he would never get back.

“Are you prepared to do this the rest of your life?” she asked one day.

“Ruby,” Bell answered, “you tell me what to do.”

“Transplant,” she said.

Turning Point

“I needed help,” Bell recalls. “I had to overcome my own ego and a certain amount of arrogance about my situation. Ruby Codjoe really helped me turn my life around.”

“When you are in your 30s and dialysis is the rest of your life, that means stopping everything and coming in three times a week,” she says. “This illness is no joke.”

To qualify for a transplant, he’d first need to drop a significant amount of weight—a process that involved bariatric surgery—in addition to making a dramatic change in his eating habits. Codjoe helped Bell navigate the complicated process of scheduling bariatric surgery and, eventually, getting added to a kidney recipient list. With her support, Bell adopted a diet and workout routine that led to a total body transformation and, ultimately, a new kidney.

“Ruby and everyone at Trinitas were amazing,” he says. “I felt really fortunate that they were with me throughout the process.”

Not that any of this was a slam-dunk for Bell. On the contrary, just three months after he lost the weight and was added to the kidney recipient list, he got the call in the middle of the night that there was a match for him. He knew that some patients wait years for this call, but he said Thanks but no thanks.

Mentally and emotionally, Codjoe says, he just wasn’t ready. “It was just too soon.”

Fortunately, when the call came again six months later, Bell was good to go. A donor kidney is only viable for four to six hours. He was instructed not to eat anything until the hospital was certain it was a perfect match. When Bell got the thumbs-up a while later, he made his way to the kidney transplant program at Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center, in Livingston. The procedure went smoothly, taking about three hours, and Bell was discharged a week after doctors determined his new kidney was functioning.

Rock Solid

Five years later, Bell (right) is eating well, working out religiously, and dealing with the cocktail of anti-rejection drugs he must take for the rest of his life. He is also a rock-solid 230 pounds.

“You would think he’s a championship body builder,” Codjoe says. “His life has changed totally.”

“The hardest part was the lifestyle change,” he says. “Getting up early to hit the gym every day, making better food choices, just having that discipline. Actually, the working out has been the easy part.”

Bell will be the first to tell you that the journey to significant, sustained weight loss is a formidable one—both mentally and physically. He’ll also be the first to tell you that if this is what stands between you and a lifetime of dialysis, it’s a journey worth toughing out…and that, if you need someone to walk with you on that journey, he’ll be the first to sign up. Bell is just a phone call away from the team at the Linden Dialysis Center. When the Trinitas staff needs someone to speak with a patient who’s losing hope, or to deliver a motivational talk to potential kidney transplant candidates, he’s happy to oblige.

“Today, when I have somebody who is struggling—especially a morbidly obese younger person,” says Codjoe, “I call Khalil and tell him there’s someone here who needs his support, someone who needs to hear from him what’s involved in the bariatric surgery and the transplant process.”

“I’m happy for the chance to share my story if it helps others,” Bell says. “I feel blessed every day.” EDGE

Editor’s Note: Erik Slagle has been writing health stories for EDGE for a decade. He was among the first to sound the alarm on the hidden dangers of vaping in the 2018 feature “Blowing Smoke.”

By pulling out all the stops, have we inadvertently pulled the rug out from under our best young athletes?

The intense pressure experienced by athletes at the top of their sport and the apex of their abilities is nothing new. It comes with the territory and is amplified exponentially when the stakes are highest, the competition is fiercest and the whole world is watching. The best of the best separate themselves from the pack at these make-or-break moments, digging deep and finding ways to meet or exceed the fantastic expectations heaped upon them. Until, one day, they can’t. Or don’t. Or won’t.

And we are stunned.

We know that Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka are made of flesh and blood and sinew—they may be marvels of sport, but they are not part of the Marvel Universe. Yet we don’t really understand what nudges them off the rails, do we? Biles opted out of the Olympic all-around gymnastics competition when her internal wiring betrayed her. Osaka took a mental-health vacation from tennis at the height of the spring/summer season. More surprising than their decisions—and more alarming than some of the public criticism they shouldered—is the eye-opening realization that they are not the exception in sports. They are actually the rule.

An Unexpected Twist

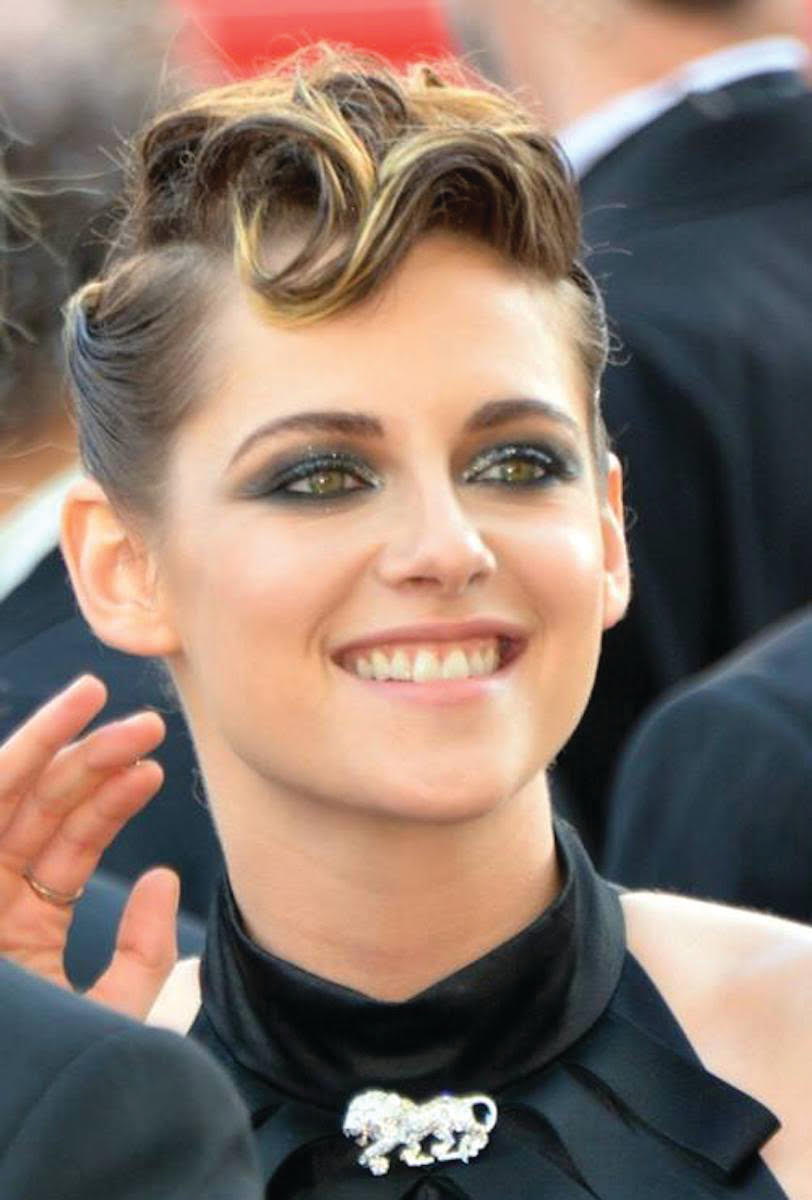

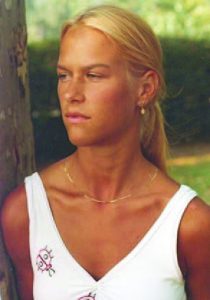

On July 27, 2021, inside the physically crowd-less Ariake Gymnastics Centre, Simone Biles (right), leading her team into the Tokyo Olympics finals against the Russian contender

Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil Fotografias

s, elevated off the mat with her usual power and grace…and failed to perform the 2 ½ rotation vault she had nailed countless times. She scored only 13.766 points, putting Team USA behind in the competition for the first time in almost a decade. Her failure on her sport’s biggest stage left television commentators stunned and her teammates speechless. What Biles did next shocked the world of competitive sports: She publicly withdrew from the Olympic finals, citing non-injury related mental health issues.

Peter Menzel

“I just felt like it would be a little bit better to take a back seat, work on my mindfulness,” Biles told reporters. “I just need to let the girls do it and focus on myself.”

Sian L. Beilock, the president of Barnard College and a cognitive scientist told The New York Times, “I applaud the fact [Simone Biles] was able to ascertain that she wasn’t in the right state of mind and step back. What a hard thing to do. There was so much pressure to continue. And she was able to find the strength to say, ‘No, this is not right.’”

Biles later credited Naomi Osaka (left)—who withdrew from the 2021 French Opens to focus on her own mental health and depression—as providing the motivation and courage she needed to put her own mental health first. Osaka had disclosed her decision to withdraw during the French Open on Twitter; she had been unable to manage her mental health, depression and press conference anxiety ever since her controversial 2018 US Open finals victory over Serena Williams, during which she endured the jeers and boos of a crowd that favored Williams.

Both Biles and Osaka had their critics, of course, some quite harsh. However, they received an outpouring of support from fellow elite-level athletes, who understood the immense, round-the-clock pressure to which they are subjected. Knowledgeable fans by and large echoed this support, as did most in the media. The two young champions compete in sports that favor youth physically, but demand a level of mental maturity that appeared to be beyond their grasp. And it just got to be too much.

An Epidemic

The thing is, Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka are not one-offs. Indeed, every year, countless young elite-level athletes on the fast track to stardom—many still young teens or pre-teens—are overwhelmed by pressure and expectations placed upon them by parents, coaches, fans and friends, and begin to hate the thing they loved the most. Unless you know them, or they are your kids, their stories go untold. Most youth sports programs, in fact, are set up to cull out the physically fragile or easily upended and push the rest ever forward. Although the survivors may gain confidence in their growing skills, the pressure cooker only grows more intense as they near the top of their sport.

Past a certain level, athletes will acknowledge that this unrelenting pressure—as Billie Jean King once said—is a “privilege.” But how do you explain the meltdown of a superstar? And, more importantly, what does that tell us about how young athletes are being raised today?

Studies done on the mental health issues of elite athletes give us the same picture over and over, and it’s kind of stunning. A study on NCAA Division I athletes found that 23.6% of the individuals included in the study met the clinically relevant level of depressive symptoms, with female athletes being nearly twice as likely as male athletes to experience depression. The prevalence rate for American college students, if you’re wondering, is between 7% and 9% depending on the study.

A UK study found the prevalence of mental health issues among elite athletes to be 47.8% for depression and anxiety and 26.8% for signs of distress. A similar study in Australia found the prevalence rate for mental health disorders overall to be 46.4%. A study in Sweden revealed that lifetime prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes was 51.7% (females 58.2%, males 42.3%).

“The professional consensus is that the incidence of anxiety and depression among scholastic athletes has increased over the past 10 to 15 years,” says Marshall Mintz, a New Jersey-based sports psychologist who has worked with teenagers for three decades.

Isabella and Vinny

Swimming World Magazine

The story of Isabella [last name withheld], a prodigal lacrosse player who started to play when she was in first grade, is not unusual. Excelling at the game from the start, she gave up on other sports she enjoyed, including basketball and soccer, to optimize her shot at a college scholarship. Sure enough, Isabella earned a full ride from an elite college during her sophomore year in high school. What she loved most about lacrosse was the attention it garnered in her hometown. Everyone was rooting for her, and that made her play and practice the sport even harder. That summer, Isabella tore her ACL and was unable to play for eight months.

“It was my worst year ever,” she recalls. “I’d grown up playing lacrosse, and I had no other hobbies. So when you don’t have it, you’re like, What am I going to do?”

Like so many other young athletes, she had been pushed and pressured by her peers, her parents and coaches to focus solely on the sport she was good at—naturally, with love and caring and unqualified support. She practiced day in and day out, cultivated an athletic identity and, in the end, all this over-practice made her more vulnerable to her knee injury. With nothing else to occupy her mind, and the sight of her peers moving ahead with their lacrosse tournaments while she had to take up painful physical therapy, Isabella soon developed an eating disorder. In the end, she chose to give up on the sport to which she had devoted a decade of her young life, deciding instead to pursue a university degree and a career outside lacrosse.

Isabella’s story is hardly unique. Thanks to the changing nature of youth sports, there is an Isabella in almost every town in the country. In 2018, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) cited two independent studies that strongly suggested that an intense, year-round focus on one sport leads to a much higher risk of burnout and injury in young athletes, as they routinely spend excessive hours per week training. “Youth sports has experienced a paradigm shift over the past 15 to 20 years,” the AAOS noted. “Gone are the days filled with pick-up basketball games and free play. Kids are increasingly specializing in sports.”

Vinny Marciano, a swimming prodigy from New Jersey, was considered by Swimming World and other authorities in the sport to be one of America’s best young swimmers in the run-up to the 2016 Olympic Games. He was the New Jersey 100-yard freestyle champion, and the 2015-16 All Daily Swimmer of the Year, propelling Randolph High School to win the team title despite suffering tendinitis earlier that same year. He missed making the 2016 Olympic by just 0.27 seconds in the 100-meter backstroke. A year later, Marciano all but disappeared from the world of competitive swimming.

In a sport where obscurity and glory are often separated by mere fractions of a second, Marciano knew what he had to do. After failing in the Olympic trials, he joined an even more intense swimming club 90 minutes from home, where he had to put in three-hour practice sessions straight after school, stay overnight with a teammate, get up early and get through two more hours of practice before arriving late to school the next day. For six miserable months, these were his Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with additional solo sets by a coach at a local YMCA. His grades tanked and, finally, he told his parents he did not want to keep going like this.

According to Jay Coakley, a leading sports sociologist and author of Sports in Society: Issues and Controversies, parental pressure doesn’t need to be explicit and heavy-handed in order to push a young athlete past his or her comfort level. Instead, just the child’s awareness of the time and money sacrificed by their parents is enough pressure to make the child keep playing long past enjoyment.

In the end, Marciano completely gave up on competitive swimming to get away from the misery of always trying to climb up a never-ending ladder. He found challenge and enjoyment in a much more leisurely sport: rock climbing. Had it not been for the intense training pressure felt by Marciano—a swimming prodigy by most accounts—after coming up short in Olympic qualifying, the swimming world might have witnessed another Michael Phelps.

Is This PTSD?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) as a condition of persistent mental and emotional stress occurring as a result of injury or severe psychological shock. While the PTSD symptoms in athletes with traumatic injuries, such as a concussion or a torn ACL, are well-studied, that is not the case for a very large number of elite athletes who are subject to emotional and psychological trauma in the form of bullying, humiliation, body shaming, being belittled in front of teammates by coaches or any other similar traumatizing emotional experience.

Former Olympic martial artist and (now) sports psychologist Caroline Anderson brings some personal insight into her new profession. “In my private practice,

I see a lot of athletes—many of them quite young—who have been traumatized in some way as a result of being an athlete and their involvement in sport,” she says, adding that, in addition to serious injury, trauma ranges from conflict with coaches, teammates and sporting bodies to bullying, politics, unfair selection processes and the embarrassment and shame that accompanies less-than-expected performance.

In some cases, the source of PTSD symptoms can be something entirely separate from the performance pressure of an athlete’s chosen sport. Simone Biles was among the scores of U.S. gymnasts sexually abused by team doctor Larry Nasser. During testimony before a Senate Judiciary Committee, Biles was reduced to tears when discussing her experience and its long-term aftermath.

“I can assure you,“ she told the committee, “that the impacts of this man’s abuse are never over or forgotten.”

PTSD symptoms affect a significant percentage of young athletes in some way or form, and for those without proper support, they linger long past the trauma. What matters most is having good support and people who actually understand their struggles. Perhaps that explains why the prevalence of PTSD appears to be much lower among traditional team sports athletes.

Basketball Hall of Famer Magic Johnson, who decades ago said, “Ask not what your teammates can do for you…ask what you can do for your teammates,” may have been on to something. Team sports inherently provide a much bigger support net for the mental health of young athletes who devote themselves to a single sport. Often, they sacrifice their social lives in their quest for excellence. In lieu of close friendships, however, they have teammates that rely upon one another for mental support.

Though not a perfect answer, it’s an improvement over the situation individual-sport athletes like Vinny Marciano live with, as they get stuck in a Sisyphean cycle of chasing perfection and dealing with often overwhelming pressure to always perform better. Indeed, a 2019 study found that individual-sport athletes are more likely to report anxiety and depression, and tend to play less “for fun” and more for goals than team-based sports athletes.

The culture of elite-level athletics, from teen sports to the pros, places a high value on mental resilience. Ironically, that culture has also been largely apathetic to the mental health needs of athletes until relatively recently. USC Sports Psychologist Robin Scholefield may have put it best when she observed that the whole healthy person is the most consistent peak performer. “If you’re not right with yourself,” she insists, “you’re not going to be okay as an athlete.”

Michael Phelps is one of the few elite-level male athletes to step forward and talk about his mental health issues, including a struggle with depression that only worsened during the pandemic. He encourages others to speak out, as he did prior to the 2016 Olympics. “It wasn’t easy to admit I wasn’t perfect,” he says. “But opening up took a huge weight off my back.”

Agência Brasil Fotografias

In 2021, three major college sports conferences—the Atlantic Coast Conference, Big Ten and Pac-12—launched a joint initiative called Teammates for Mental Health. So things are changing. Of course, the hard work still begins at home.

As a parent or as a coach, remember that not a single person has ever succeeded by blindly burning themselves out on a sport that makes them miserable. It is healthy for children to have sports dreams, but what is equally important is to make sure that the child learns other skills to fall back on in case their dreams are not achieved or are not all that they wanted them to be.

Multiple generations are responsible for creating the mess of mental health issues that can consume young elite-level athletes. Perhaps this generation of athletes, with their public platforms and social media followings, will follow the lead of Simone Biles, Naomi Osaka and a handful of others in making the world of sports more in tune with the mental health needs of athletes. Hopefully, their willingness to open up on the subject, to the possible detriment of their image and the value of their “brand,” triggers the kind of culture change that will swing the mental-health pendulum back in favor of the next generation of young, high-performance athletes. EDGE

Editor’s Note: Chuka Erike has been involved in the sports industry since his college days. In 2016, while working for the NBA, Chuka won the league’s Community Assist Award. During a career in sports that stretches back more than 15 years, he has devoted himself to working with young athletes who face high pressure and unrealistic expectations. He recently mentored Joey Spallina, the nation’s top-ranked lacrosse recruit, who is headed for Syracuse University in the fall.

Is your OTC medication doing more harm than good?

Over-the-counter (OTC) medication is one of the safest, most convenient and most affordable pieces of the healthcare picture. The average American household spends nearly $450 a year on OTC medication and related products. We trust OTC drugs, and with good reason: They are FDA-regulated, securely packaged and, where appropriate, most doctors are comfortable recommending them before jumping right into prescriptions. They are marketed well, too. Who can say how many hours of headache, back ache and joint ache commercials the average adult has watched in a lifetime? They are so ubiquitous that we pretty much ignore them at this point.

Unfortunately, there is another aspect of OTC medication that we tend to ignore, and that’s the labeling. The FDA assures their safety only when all labeled directions are followed and all warnings are carefully considered. In theory, most of us understand what this means. In practice, however—particularly while experiencing pain and discomfort—we do stupid things. And that is when OTC drugs can become unsafe. This is particularly true for individuals with coronary vascular disease (CVD). For these individuals, OTC medication can have a serious impact on heart health.

“My patients who suffer from various heart diseases are mostly older and therefore very vulnerable to indiscriminate use of OTCs,” says Dr. Fayez Shamoon, Director of Cardiac Services at Trinitas. “One very real problem for them is that taking OTCs might interfere with compliance about taking their prescribed medications.”

www.istockphoto.com

“Popular remedies such as decongestants and nasal constrictors for the common cold can lead to serious heart consequences,” he adds, “including tachycardia and arrhythmia.”

Do I have a cold or is it really the flu? Is this indigestion or a possible heart attack? What is it about human nature that convinces us that we’re qualified to answer questions like these? Particularly when self-diagnosis only amplifies the risk when we grab an inappropriate product off the shelf. Relying on personal rather than professional diagnoses, especially when cardiac symptoms are involved, can lead to “more harm than good” consequences—for instance, choosing a popular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) to relieve arthritic lower back pain…only to find yourself in the ER after a life-threatening side effect.

For his part, Dr. Shamoon considers NSAIDs to be the most abused and dangerous class of OTC drugs. Relief from pain too often supersedes the potential risk of serious consequences, even to a healthy heart, he explains. He encourages his patients to exercise good sense and ask before adding any store-bought medication.

“I am always available to help them make wise decisions to protect their heart health when dealing with OTC meds,” he says.

Matters of the Heart

According to the CDC, heart disease has surpassed cancer as the leading cause of death by more than 100,000 annual fatalities. Another recent wake-up-call statistic is that one American dies every 37 seconds from CVD, which works out to roughly one in four deaths. CVD is a condition that affects not only the heart but the vascular system that services it, which can lead to a heart attack, angina or a stroke. Also very concerning is that around a third of adults suffer from high blood pressure, which can trigger serious heart complications.

Then there is the issue of cholesterol. While a normal level of “good” HDL is necessary for healthy cell production, a high level of “bad” LDL indicates the presence of excessive fatty deposits in blood vessels that inhibit the flow of blood. This interruption of blood flow can lead to a heart attack or stroke. High LDL is not typically accompanied by noticeable symptoms, requiring a blood test to diagnose. The Mayo Clinic recommends cholesterol screenings every year or two for men ages 45 to 65 and for women ages 55 to 65, while seniors over 65 should be tested annually.

What’s in Store

Meanwhile, the aisles at your local pharmacy are overflowing with products that promise to address medical conditions ranging from a simple cold or occasional headache to more aggressive-sounding treatments for pain and its sources. And because you’re making choices when you are not at your best, sometimes it’s difficult to remember these are only safe when used responsibly—in other words with full awareness of all positive and negative effects. It would be nice to get your doctor on the phone to help with these decisions, but that’s not always possible. In these cases, ask the pharmacist, especially if you are shopping at your “home” store. Pharmacists can access your current medications or at the very least ask you some key questions. They are perfectly positioned to recommend a specific OTC product or, more importantly, steer you away from one that may be problematic.

“Be thoughtful before you go to the pharmacy,” Sharon Greasheimer, a Registered Pharmacist and Director of the Trinitas Pharmacy Department, advises. “Go to the Internet or another reliable resource and do a little homework. Plan ahead. Put the whole picture together—your age, any diagnosed medical conditions, any other medications prescribed—and then call ahead to see if your pharmacist might be available for a brief consultation if needed.”

In the Trinitas Pharmacy, Greasheimer notes, every drug—whether over-the-counter or otherwise—requires a script from the attending physician before it can be dispensed at the hospital. The pharmacy also follows up for possible side-effects or drug reactions. However, once at home, patients shoulder the responsibility for good decision-making when it comes to OTCs.

“These are self-treatment remedies that can be useful—but only if the user is also aware of any potential risks or side effects,” she says.

When considering the purchase of NSAIDs, heart patients need to be doubly cautious. Different NSAIDs, whether prescription or OTC, work in different ways, so it’s important to ask your doctor or pharmacist which is right for you, even if you’re in tip-top health. They all come with side effects. Topping the list are digestive problems, such as stomach upset, heartburn and ulcers. More serious complications can include kidney injury, internal bleeding and severe allergic reactions. The possible risks from use of unprescribed NSAIDs are escalated when a heart issue, diagnosed or not, is present. When considering whether to start a NSAID regimen, there is currently no clear consensus regarding safe dosages and extended-use prohibitions. The best approach? Ask your physician (or cardiologist) before even setting foot in the store.

www.istockphoto.com

Survey Says…

The multibillion-dollar OTC marketplace is a battleground for your business. Over the years, ad agencies have found that the most effective way to earn the trust of consumers is with “take it from me…” testimonials, which are often accompanied with or followed by a list of side-effects, legalese and assorted other caveats and disclaimers. They work because we focus on the actors (yes, they are actors) who remind us of us, and don’t seriously evaluate the validity of what they are saying. Data collected in a recent study at Dartmouth College indicated that “80 percent of over-the-counter drug ads were found to be misleading or false.” If you’re curious, the same study also suggested that 60% of new prescription drugs being advertised were also misleading (or false).

So how surprised were we to find out that the old “aspirin a day” advice has now come under serious question? In the hallowed halls of Harvard and the Mayo Clinic, some experts are refuting the popular recommendation to take a daily low-dose aspirin to prevent heart problems. New studies reveal that aspirin therapy for healthy adults may actually be more harmful than helpful. As with most OTC medicines, aspirin can have negative side effects, such as gastrointestinal upset, ulcers and internal bleeding—especially when taken in combination with other blood-thinners. On the positive side, there are some indications that aspirin can be a helpful preventative for those patients who have been diagnosed with heart conditions. Consequently, aspirin as a preventative measure is now often reserved only for those patients with a prior history.

A monthly pharmaceutical journal, The Pharmacy Times, found that nearly nine of every 10 Americans use OTC products regularly. That’s more than 260 million consumers who make about three billion trips annually to purchase their OTC meds—at a price that can be one-tenth of a prescription drug. This space is booming, with many former Rx drugs transitioning onto already crowded shelves. In our minds, they have become “consumer goods” even though they are not.

FDA approval, easy access and attractive pricing do not make OTC drugs heart-healthy, especially where patients with cardiac issues are concerned. In the end, it is your body and thus your job to be a vigilant consumer, and that means asking the right people the right questions before bringing a cold medicine or pain reliever to the checkout counter. You never know…it could be a life or death decision.

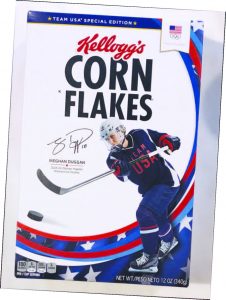

Remember when you played sports in school and there was that one kid on the other team who made you want to take a seat on the bench? You know…an athlete who saw things a split-second sooner, who was a step quicker, and who administered a hard lesson in physics if you were foolish enough to make contact. Meghan Duggan was that kid. She grew up to become captain of the U.S. women’s ice hockey team, which, after silver medals at the 2010 and 2014 Olympics, won a gold medal in 2018 in South Korea. After 13 years at the apex of her sport, Duggan hung up her skates, moved to New Jersey and, last spring, became Manager of Player Development for the New Jersey Devils. A new mom in a new job, she brings her leadership, hockey experience and keen eye for championship intangibles to a club looking to hang a fourth Stanley Cup banner from the rafters at the Prudential Center. No pressure, right? EDGE caught up with Meghan to talk about life on her new home ice.

Andrew MacLean/New Jersey Devils

EDGE: Sports fans don’t realize what’s involved in the transition from star player to team executive. For some, it’s a natural transition, for others not so much. What has been the easiest part for you these past six months or so?

MEGHAN DUGGAN: The easiest part of the transition is coming into a culture that’s based around what I’ve built my life around, the sport of hockey. I’m working with hockey minds and that “hockey family” mentality, which I love. There are a lot of people in the Devils organization, and pretty much everyone with whom I interact on a daily basis has played at a high level and was a leader at a high level. I’ve felt welcomed since day one.

EDGE: What has been the most challenging aspect?

MD: Continuing to learn the ins and outs of building a successful NHL team. For a long time, I’d just had to focus on playing and leading a team as an athlete. Now I am digesting and understanding all of those components in a short period of time, including development, analytics, amateur scouting, pro scouting— just learning the terminology and how all the different groups work together toward the same goal—so that I can add value in the best way possible.

EDGE: Having been the captain of a successful team, does that give you a sixth sense about young players who might bring a similar quality to the Devils?

MD: Filling that role for so long, having to go through different experiences and highs and lows, it shaped me as a person and the leader that I wanted to be. I was challenged many times and learned a lot about having the will and the drive to compete. Using what I learned as a captain to identify and help develop great leaders and great culture is something that I want to bring to the Devils.

U.S. Women’s National Hockey Team

EDGE: With the women’s national team, you often found yourself advocating for financial support and better conditions. Is it a relief to be working for a team where those challenges don’t exist?

MD: You know, every situation brings its own challenges. On the women’s side, something that we’ll always continue to fight for is visibility, accessibility and resources. In the NHL, there certainly aren’t those struggles, but we have our own set of hurdles to clear. In both cases, that’s what you have a team for, and why you need a great group of people strategizing and solving problems. But advocacy is always going to be a part of me. Sports has given me so much in my life, I am always passionate about advocating for kids to be involved in sports and around sports, and to have great role models in general. I was recently named president of the Women’s Sports Foundation for 2022. I’m really looking forward to finding ways to marry my two roles, generating excitement about the Devils among young girls and women, and getting them to games here in New Jersey.

EDGE: I am curious about your thoughts on something. I believe that American sports fans don’t quite know how to process a silver medal, particularly in a team sport. What was it like to win silver twice and how did winning gold in 2018 alter that perspective?

Upper Case Editorial

MD: That’s a good question because the way you think about it does change and evolve. As an Olympic athlete, and a hockey player specifically, all the training I did in the four years leading up to the 2010 and 2014 games—and then winning the silver both times—there was a little sting at the beginning, as you might imagine. You don’t train and prepare and do everything you do for second place. You’re not running on the treadmill ’til exhaustion thinking I can’t wait to win silver. In hockey, in order to win a silver medal, you have to lose in the final game. So as competitive as I am and our teams were, it’s tough to swallow at first; it takes a little time to get over that and adjust. But when you are able to step back and reflect on the journey and the process and the lives you touched on the way there—and what it does mean to bring a silver medal back to your country—you can be proud of it.

EDGE: So what happened between 2014 and 2018?

MD: Our team really transformed and took on the challenge of becoming something bigger, becoming something more than silver, figuring out what the missing piece was to get the gold medal. We worked hard for four years and lived by the motto You can’t stay the same and expect a different result. We had to dig a little deeper and we were able to do so. I am very proud of our team for winning the gold medal—and then how, as a group, we used that gold medal for advocacy work, as well.

EDGE: How would you describe Meghan Duggan as a player when you were at your best?

U.S. Women’s National Hockey Team

MD: I’ve been a really competitive person since I was young. I’ve always held myself to the highest standards when it comes to competing and work ethic and the will to do the little things to help my team—win battles, block shots, kill penalties, go to the dirty areas to score goals—so I definitely brought those elements to my game. When I was at my highest level, I was a high goal-scorer and point producer. But as you get older and younger players come in, you turn your identity into something different. I was always a physical player who protected my teammates, created havoc, brought energy and was a really hard player to play against. To be honest, those are qualities I admire and look for in a player in this day and age. It’s not something everyone has, and it’s not something you can pull out of a player. It’s something deep inside players who I find exciting to be around and watch.

EDGE: What’s it like playing on a line where everything clicks?

MD: It’s the best. I had that multiple times in my career. Every night you’re showing up and your line is putting up three, four goals and you’re on a roll. It’s a nice feeling when you find that chemistry. On the flip side, being able to work through the adversity when that’s not happening—I think great players do that.

EDGE: Is that a coaching thing or something the players work out themselves?

MD: It’s a combination. There’s a lot that goes into it, which is something we deal with on the development side with the Devils. You’re trying to develop players from a technical, tactical, mental and physical perspective. However, as a player, when things aren’t going well, you have to be able to evaluate all of those components of your game, too, and find your way out of it.

EDGE: When you were growing up, playing youth hockey in Massachusetts, the American women’s team won the gold medal in Nagano. How did that change your life?

MD: My teammates and I have always said that the 1998 women’s team lit a fire in us. It really did change my life because, growing up, I had idolized NHL players. I thought I’d go on to play in the NHL, because that’s all that I saw. Being able to experience women playing hockey at an elite level was life-changing for me. And then having the opportunity to meet some of them, to put their gold medal on, to put their jersey on, that was pretty special for a 10-year-old kid. From that moment, I told everyone I knew that I was going to play in the Olympics and captain the team to a gold medal. I built my life around it.

EDGE: At what point did you feel like you were being groomed for the national team?

MD: During my freshman season in college at the University of Wisconsin, when I was invited to compete at the training camp for the women’s national team, right after Christmas. From that camp I made the World Championship team in the spring. After that, I stayed on the team for 13 years, until I retired a couple of years ago.

EDGE: You’ve talked about what you like to see in a player. Are you going to be doing a lot of scouting in your role with the Devils?

MD: That’s a major component of my job. Our department has to understand how the young players we’ve drafted or the young pros on the team or the prospects out in the field are developing, and then give them the resources to enable them to become the best players they can be.

EDGE: Is there a “Devils kind of player” that the team looks for?

MD: When you think about what the end goal is, for the organization to win a Stanley Cup, it’s more about finding the pieces that fit together in a great puzzle in order to do that. And there are a lot of pieces: your high-skilled players, your energy players, your identity players, your players who will go through walls, your goal-scorers. The Devils are very well organized. The way we go through discussions and challenge each other to be the best we can be, it’s very exciting to be a part of that. We have dynamic leadership in Tom Fitzgerald, our general manager. I’ve already learned a lot from him. As for my role, I interact with a lot of different groups within the organization. I’m in on the hockey-specific stuff and understand how players are playing right now, and where they are physically. I also have to understand who are the amateur players who might potentially be drafted and fall into the hands of the development group. So I’m still learning, but that’s what I love about my job—it gives me a unique opportunity to see how the organization runs from a number of different scopes.

EDGE: You have two very young children, so you probably get asked a lot whether you’ve gotten them on the ice yet?

MD: My son will be two at the end of February. We got him out on the ice once last winter at 10 months and I look forward to getting him on skates this winter. My daughter was born this fall and we’ll definitely be getting her on skates, as well.

EDGE: Are they looking like forwards or defensemen at this point?

MD: Too early to tell. But we’ll support them either way. I don’t know that I’d be a great goalie parent, though. I think I’d be too nervous to even watch the game. So we’ll steer ’em away from that [laughs]. We’ll see. EDGE

Editor’s Note: Meghan Duggan is an iconic figure in the history of women’s ice hockey. She was a First-Team All-American and the NCAA’s top scorer in 2010–11, and won multiple honors as the top player in women’s college hockey that season. She played six years of pro hockey following her graduation from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a degree in Biology. In her eight career trips to the World Championships, Duggan and her U.S. teammates won seven gold medals.

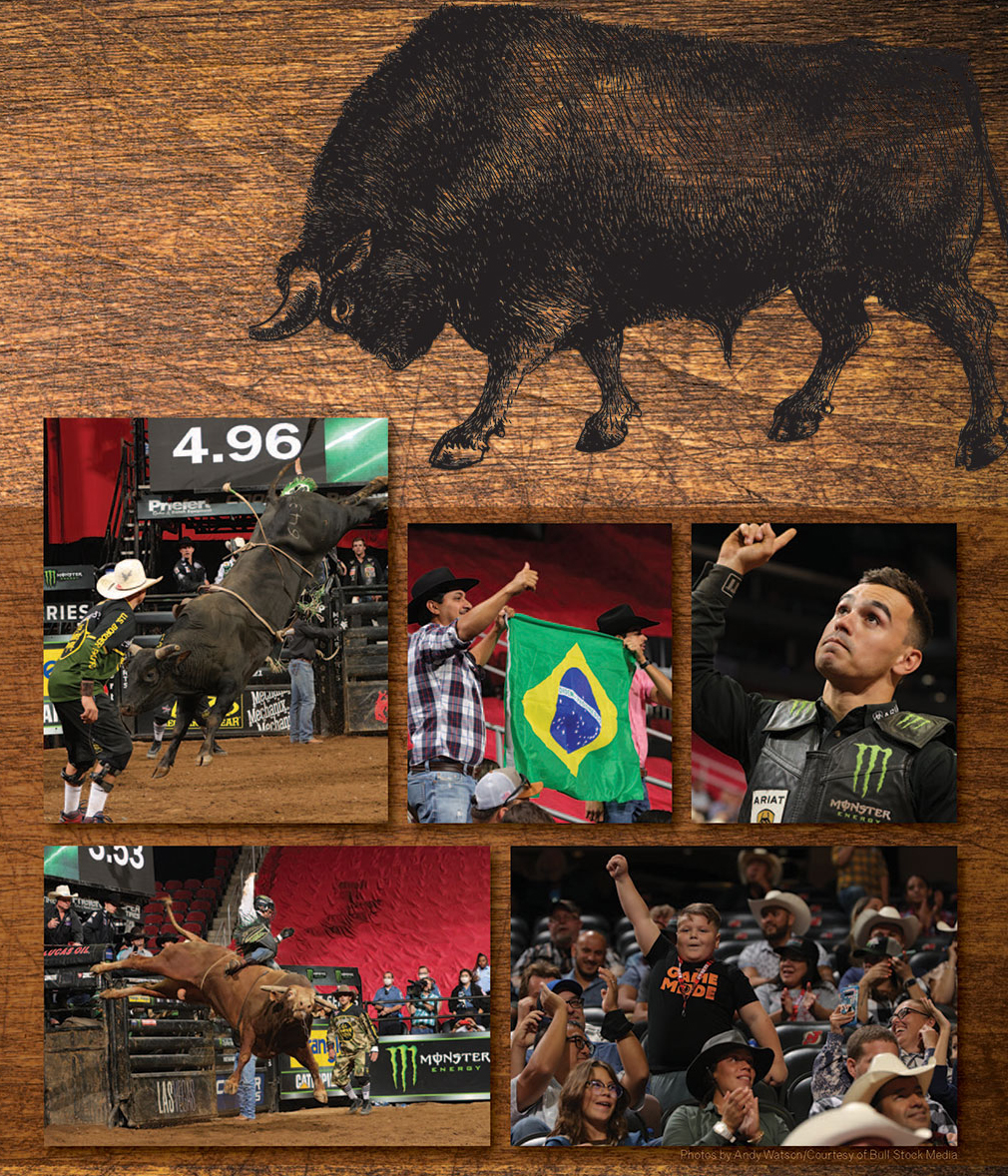

The Professional Bull Riders (PBR) circuit rumbled into the Prudential Center back in September for the first time in seven years as part of the “Unleash the Beast” tour. The PBR Newark Invitational showcased the talents of the sport’s top-ranked riders, including past champions Cooper Davis, Kaique Pacheco and Jose Vitor Leme, all of whom were in the running for the coveted Golden Buckle. Leme, a 25-year-old Brazilian, captured the New Jersey event—his seventh of the year—on the way to tying the all-time record of eight wins with a victory at the PBR World Finals in Las Vegas last November.

Photos by Andy Watson/Courtesy of Bull Stock Media

Photos by Andy Watson/Courtesy of Bull Stock Media

The backyard sports court has joined a growing list of value-added home improvements.

Almost every person with older siblings remembers the first time they beat them in a game of backyard basketball. In those moments, the trees become spotlights, the chattering birds are transformed into thousands of roaring fans, and your Dorito-stained tee-shirt morphs into the jersey of your favorite sports team. Your backyard is no longer a backyard. It’s a colosseum of greatness and you are the superstar gladiator. What better way to gift your children that shot at glory than to build a sports facility right there in your backyard? It serves as a haven for family bonding, youthful development and boundless joy—with the added advantage that you control important elements of security and supervision. It’s also a great way to unglue your children’s faces from their screens and get them moving outside.

TD Sports West, Inc.

The traditional backboard-in-the-driveway set-up is still a popular choice, but you know kids these days. It may take something a little cooler (and pricier) to grab their attention and secure their buy-in. There is also another consideration: You may want to use it, too. So, depending on your budget, the size of your property and the interests of you and your children, everything is on the table, from batting cages and field hockey goals to basketball and tennis courts. Fortunately, you may not have to pick one and live with it forever. There is something called a “combo court,” which enables you to play up to 15 different sports using different equipment and markings. For instance, the same physical space can accommodate tennis, basketball, pickleball, badminton, volleyball, tetherball and handball.

Most people start with a single sport in mind and either go to their local sporting goods dealer for suggestions on builders, talk to a friend or neighbor who has installed a good-looking court, or poke around the Internet for ideas. All three have their pluses and minuses, but regardless of the path you choose, it’s a good strategy to begin with a checklist because this is an investment that, ideally, you’re only going to make once.

www.istockphoto.com

The Rule of 9

I checked in with TD Sports West, the go-to supplier of the Sport Court, a patented modular game court that is popular in the western United States. Marty Levy, the owner, has been at this awhile and helped me come up with the following decision-matrix “to-do” list:

1 Think about the sports your family plays. Take into account the age of your children, what they’re currently into, what they might be into in the future, and what athletic endeavors you yourself enjoy.

2 Think about how much space you have, and what percentage of that space you’re willing to devote to this project. Modular surfaces come in all different shapes and sizes. However, at the minimum, you’re looking at a 25’ x 30’ space for a usable basketball halfcourt. A tennis court-sized surface needs to be at least 60’ x 120’.

3 Check to see if your town requires you to get a permit to build the court you want. Be aware that most municipalities will not allow you to build a court in close proximity to any wetlands or over a septic system.

4 Take note of large trees on your property. Over time, their roots could damage the surface.

5 Consider where access to the construction site is likely to be. You may have to remove a fence or wall, sacrifice some landscaping, and vacate your driveway when the trucks and heavy equipment show up.

6 Pick the appropriate surface. Options include concrete, asphalt, synthetic turf, tile and modular surfaces. More on this later.

7 When it comes to equipment, triple-check to see that you’re dealing with a high-quality, reputable manufacturer. If something seems like it’s too good of a deal, it probably it.

8 Check to see if the surface you choose comes with a warranty (many do). Read that warranty carefully and ask questions in case any future troubles arise.

9 Even if you are a skilled do-it-yourselfer, don’t do it yourself. Hire a professional who’s done it before.

Before signing on the dotted line, there are some other considerations you need to be aware of. Local zoning ordinances are your responsibility to understand, not your builder’s—no matter what your builder says. If you need to submit plans to the town or adhere to rules governing “accessory structures” (such as ramps or fences), by all means do so. Also be aware that your town may have regulations about the height, purpose, or proximity to neighboring properties even when your neighbors have given you a friendly thumbs-up.

Finally, give your insurance agent a call to see if your new addition will trigger any policy complications. Most backyard sports complexes don’t pose any issues, save for trampolines and skateboarding ramps, due to their high injury liability, but also check if you are covered should a neighborhood kid take a spill and end up in the ER.

www.istockphoto.com

Cost vs. Benefit

If this is sounding more complicated than it should, well, what isn’t these days? Is it worth the expense and hassle? I spoke with Marty—not the TD Sports guy, a different Marty—a father of two I remembered from my old neighborhood. Back in 2003, he built a nice basketball halfcourt for his children. He has never regretted that decision: “I would just say that the best part of the court was my kids thinking that they were playing at the Staples Center and dunking the ball like Kobe Bryant. I think those are priceless things for families to cherish and a motivation for people to build something like that. When you’ve got a family, do you want to create the place where all the kids hang out? I definitely wanted to do that. Things like having a Slurpee machine, and always having snacks and water, and being the place that was comfortable for all the kids was really important to me.”

Now to the $64,000 question: expense. First of all, can a backyard sports court actually cost $64,000? Oh, yes. Should is cost that much? Let’s take a look at some common backyard sports options and their costs.

Where basketball courts are concerned, the first decision to make is whether you want a full court or a halfcourt. A full-length, NBA-sized basketball court is 50’ x 94’ (4,700 square feet). One step smaller is a high-school basketball court, which is 50’ x 86’ (4,300 square feet). You can go with something smaller, of course, with hoops on each end. If you’re like most people and you just don’t have the space for end-to-end action, be aware that halfcourts come in all different shapes and sizes. Halfcourts range in size from the 25’ x 30’ for a “mini” halfcourt (750 square feet), to a “regulation” halfcourt, which is 50’ x 45’ (2,250 square feet).

www.istockphoto.com

The price of an outdoor basketball court depends on the surface you select. In general, your options are cement, asphalt, tile or a modular surface. Every cost has gone up during the pandemic, but assuming things get back to normal during the upcoming building season, a concrete court will cost you between $1.25 to $1.75 per square foot for the concrete itself, and $2.50 to $8 per square foot for its installation. Let me do the math for you: A full-sized concrete court will cost you between $15,000 -$45,000, while the larger halfcourt will cost you $8,500 to $22,000. A mini halfcourt will land somewhere in the $5,000 to $10,000 range. Asphalt costs around $4 per square foot, so you’re paying around $19,000 for a full-sized court, $17,000 for a high school full court, $9,000 for the large halfcourt, and $3,000 for an asphalt mini court. Keep in mind that while asphalt may be cheaper, it’s more likely to cause injuries due to its naturally uneven and abrasive surface. My knees are still marked up from my blacktop basketball days. Snap-together tile surfaces cost anywhere from $3.50 to $4.50 a foot, so their prices are pretty similar to asphalt. What’s nice is that they often come pre-painted and they’re relatively simple to install. Lastly, modular courts are made of an advanced interlocking polymer web providing a cushioned surface that is both easy on the body and easy to install. The material is more expensive upfront but cheaper to work with. A lighting system to keep the games going after dark can be installed for under $2,000.

Tennis courts are easier to price out because they tend to be the same size. A tennis court’s dimensions, as previously noted, are 60’ x 120’ and you can’t really skimp on that number. The key decision is your surface option. Clay courts are typically the cheapest surface but require the most maintenance. You’re looking at a price range from $30,000 to $80,000 for a clay court depending on the type of product you use and the difficulty of site preparation. Clay courts are easier on the knees and the budget, but require up to $2,000 a year in basic maintenance and have to be “closed” for the winter and “opened” for the spring by a professional service. Most people in New Jersey opt for a hard court, which involves a concrete base and an acrylic surface. This type of court will cost you $60,000 to $120,000 but requires minimal maintenance. The only foreseeable upkeep is repainting worn court markings and occasional re-surfacing of the acrylic if any cracks appear, which can get expensive if you are especially picky about the playability of your court.

TD Sports West, Inc.

There are still some people crazy enough to install grass courts, which range from $50,000 to $150,000 but require a fat wallet and a skilled greenskeeper to maintain. The folks who are in this business are a dying breed but they are still around. The next best thing to grass, synthetic turf courts, run $75,000 to $100,000 to install, and are obviously much easier to maintain. However, they don’t offer anything like the feel of playing on a real grass court. Regardless of your surface selection, you will need fencing for your tennis court, which typically adds between $5,000 and $15,000. For lighting, if your neighbors and your town allow it, you can double that cost. Finally, set aside at least $3,000 to cover the cost of leveling your property and another $4,000 for creating some kind of drainage system, regardless of the court you plan to install.

Combo Courts

The combo court is a relatively new player in the sports-court game and it makes me wonder why these things haven’t been around longer. Time is an unstoppable force and, one day, your little ones will have grown up and flown out of your home nest. Existential crises aside, you are now faced with a colossal concern: What am I going to do with my outdoor sports court now that the kids are out of the house? The most obvious answer is to use the court yourself.

Which is why more and more homeowners are looking at combo courts, which, as mentioned earlier, can accommodate several different sports as tastes and interests and ages change. And so what if your above-the-rim days may be over, or your knees can’t tolerate more than the occasional game of tennis? Think of the other ways you can put a large, flat flexible space to work. Backyard parties and events—perhaps for a local school or favorite charity—are a great reason to keep them in play. My old neighbor, Marty, is already thinking about repurposing his basketball court (and Slurpee machine) in ways that have zero to do with basketball.

And why not? The time, money and energy you put into creating an awesome backyard sports court does not have to be about short-term payback. With thoughtful planning, it can pay dividends for the rest of your life.

“Coq au vin charmed me, its rich red wine base picking up on the sweet smokiness of bacon, with onions, carrots and mushrooms fine in their role as sponges.”

Faubourg

544 Bloomfield Avenue, Montclair

Phone: (973) 542.7700

Web: www.faubourgmontclair.com

Instagram: @faubourgmontclair

Traffic jam at the front door! Everyone’s entering through the same portal that leads into a courtyard of a dining/bar space reminiscent of an era when congregating was normal. It’s normal right now at Faubourg, a vast bi-level space in downtown Montclair that exists at the crossroads of a special-occasion restaurant and a neighborhood joint.

A neighborhood joint for those who expect fine foods, fine wines, fine cocktails, fine brews and fine service every night of the week, I should say.

Owned and operated by a pair seasoned in such operations, courtesy of years spent working for the New York-based superstar toque Daniel Boulud, Faubourg is the domain of chef Olivier Muller and front-of-house master Dominique Paulin. In the summer of 2019, they opened the place that has been termed a brasserie and is a brasserie in terms of spirit and style, if not size.

Intimate, Faubourg is not. I found myself in the company of dozens of people upon entering the extensive sidecar space: Some were crowded at the bar, others clustered at tables. A sizable crew were delivering food and drink to diners, as well as incoming folks like me.

Faubourg, it seems, is doing what many are saying in these pandemic days cannot be done: plying the upscale-experience, fine-dining trade. That’s dead, many chefs who have made careers out of haute cuisine have claimed; if it can’t be boxed for take-out, it won’t fly. Yet even during the earliest COVID surges, Faubourg maintained its haute-experience mission, all the while creating, within its expansive walls, spaces that offer those gathering for after-work drinks and bites or six-top birthday celebrations just what they need. The overall affect is of a huge party, be it on an ordinary Tuesday or a hustle-for-a-rez Saturday.

We’re in the more subdued mezzanine, upstairs from the truly bustling main dining room where conversation requires some deep leaning-in. Our second-floor perch, near the various private dining rooms, is where you want to be if space is your priority.

The chickpea panisse is what you want to order for your table, if starting things off with the taste of silky, slightly nutty deep-fried nuggets ready for smearing in an herby aioli is your jam. Coupled with a glass of rosé, anything sparkling, or a cocktail that brings with it a bit of a pucker, it’s as South of France as Montclair can be.

Worried that you’ll finish off those crispy chickpea flour squares in an embarrassing nanosecond? Snag as well the barbajuans, a Swiss chard-and-ricotta-filled fritter that looks like a mini, lightly fried ravioli. I’ve only had barbajuans, which are originally from Monaco, in a larger half-moon shape. Faubourg’s little squares provide for more advantageous one-bite, get-it-all-at-once eating, complete with flecks of parmesan and snips of chive. Or it could be the hint of lemon the kitchen sneaks in. That’s possible. Probable, actually.

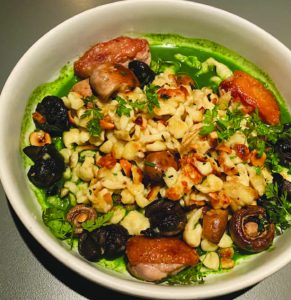

I’ve had Faubourg’s escargot before; it’s still a winner. It’s a stew, really, of snails, meaty chicken oysters, hazelnuts and a bounty of spaetzle, some browned and crunchy, some soft and chewy. The parsley puree, peppery, piquant and verdant, is the loving mother of this dish: there to give every other element a hug.

Exacting knife skills are required to give tuna tartare elegance. Neatly cubed sushi-grade tuna and pert rounds of cucumber betray such skills. But this starter needs more than the suspicion of lime and a crumble of buckwheat crisps to give it pizzazz. And: Chives need to be tasted before being sprinkled on top (they were mighty mild). Those pretty flakes of red pepper? No zing at all. Past prime, perhaps? However, the ingredients are primo in the crab salad: Mounded atop frisee and arugula were slices of earthy heart of palm, buttery favas and sweet crab. While billed as a lump crab and citrus salad, there were but a few slices of mandarin-like fruit in the shallow bowl. More citrus, please, to brighten the toss.

The orecchiette with lamb ragout came alive thanks to the nutty, slightly bitter Ligurian olives on board. You don’t need a lot of the revered taggiasca olive to make an impression, particularly when lamb is involved. Good, sharp parmesan needs a better-quality creamy-cheese companion than the shy-on-flavor number spooned into the center of the dish. A riveting Garden State burrata is out there, waiting to be found.

Coq au vin charmed me, its rich red wine base picking up on the sweet smokiness of bacon, with onions, carrots and mushrooms fine in their role as sponges. Add a soupcon of spaetzle to the gravy and be happy. Beef bavette is sliced, its thick slabs reconstructed to look like a most desirable meatloaf before being set upon a hefty rasher of shredded oxtail. When accompanied by a classic soubise—a bechamel infused with slow-cooked onions—as the beef duo is here, it’s the ultimate in meat-and-potatoes eating. Good thing, too, as the billed spinach merely peeked out from under the loaf of meats. Why so skimpy a portion of greens? Guess there are folks who want it that way. Lemon sole, slightly overcooked, had by comparison a near-bushel of browned cauliflower as a plate mate, along with a few florets of broccoli, cooked green grapes, capers and slits of mushroom. The brown butter sauce wasn’t enough to rev up the fish, which made me wonder if that’s why someone in the kitchen slipped in a wash of soubise.

Anyway, even though the pear-hazelnut cheesecake was shy on pear, it was resolutely creamy and the accompanying quenelle-shaped oval of hazelnut ice cream deserving of being called divine.

Faubourg is much about repeat diners, those who find their loves on the menu and their choice of top-notch beverages at the bar…and then find themselves in a community of many as a Faubourg regular. EDGE

Editor’s Note: We welcome Andy Clurfeld, the magazine’s food critic since 2009, back to the pages of EDGE following a year during which New Jersey’s top restaurants weathered unprecedented challenges and uncertainty.

10 Minutes with…

Barry H. Ostrowsky

President and Chief Executive Officer, RWJBarnabas Health

Gary S. Horan, FACHE

President and Chief Executive Officer, Trinitas Regional Medical Center

EDGE: As of January 1, Trinitas is now part of the RWJBarnabas Health system. What were some of the boxes that needed to be checked for this to happen?

Horan: Ensuring that we maintained our Catholic mission was of primary importance to us. It has been, and will continue to be, a core component of Trinitas, which remains a Catholic institution with continued oversight by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth. We also looked to partner with an entity that could help us advance our mission of caring for our most vulnerable citizens.

To be successful in the future, we also knew that health systems would have to coordinate care more seamlessly among providers, hospitals and care settings. We believed that we needed to join with an organization that would enable us to continue providing care in our community for years to come—against a backdrop of healthcare trends that disproportionately affect safety-net providers like Trinitas. For instance, it is becoming increasingly difficult to recruit physicians and nurses as a standalone hospital; they are looking for more variety and better possibilities for advancement—which being part of a larger health system can provide. So, starting about five years ago, we began looking at a number of strategic partners in New York and New Jersey. When we engaged in more meaningful discussions with RWJBarnabas Health, it was evident that they were the partner that we wanted to continue to pursue.

Ostrowsky: There was complete alignment on our goals, and our mission statements are almost identical. That was a very important component of the merger. In our view, nothing needed to change in terms of the strategy and the commitment and the culture. We both focus on taking care of communities and Trinitas does a fabulous job of this. And of course, its clinical services are of the highest quality. We want to take care of more and more of the population of New Jersey in a culturally competent way and, thanks to the addition of Trinitas to the system, we shall.

EDGE: What changes might patients notice on their next visit to the hospital?

Horan: They will notice a branding change, with a new RWJBarnabas Health logo and, through advertising, they will see that they now have access to an entire system of specialists. Conversely, RWJBarnabas customers now have greater access to the things that Trinitas does especially well, such as wound healing.

Ostrowsky: When an organization like Trinitas joins another group of institutions—in our case an integrated system—it needs to get a real advantage. We were in a position to offer that. All of the presumed advantages in terms of clinical and social care are now available in a convenient, seamless way for Trinitas customers. For example, if you need a service that isn’t immediately available on-site at Trinitas, we have it in the system with an easy referral because that “seamlessness” is something that already exists within our system. Also, I should mention that we are an academic-based healthcare system and Trinitas was already teaching clinicians, which means we’ll be able to further expand our academic footprint. So patients may notice more teaching going on.

Horan: Barry mentioned social care. RWJBarnabas has a very significant behavioral health footprint, which made our behavioral program a particularly good fit with theirs.

Ostrowsky: Yes, Trinitas has definitely distinguished itself in this area. Its services are clearly accretive to our clinical success as an organization, which—together with our Rutgers partner—made us probably one of the top three in the United States in terms of the complexity and breadth of our commitment to behavioral health services. The merger adds to that in terms of scale, including the number of beds and clinicians, giving us a very wide and deep platform of social services. If individuals presenting for medical care at Trinitas are vulnerable because of food insecurity or any of the other social determinants, they now have access to a full suite of social programs. We, as a system, are able to mobilize significant resources—including financial, human capital and technology—that may have been outside the grasp of a standalone hospital, as Gary was saying earlier. I don’t like changing things that work. When you look at Trinitas—the results it has produced for the community, the culture of the institution and those who lead it—there is no reason to make any changes, other than ensuring Trinitas has the resources I mentioned to continue to do the job it has done. In terms of leadership at the management level and department-director level, it is such a great group of people. I call Gary Horan a dean of this industry and he is truly that.

Horan: I think Barry and I are both excited about what it means to have our School of Nursing folded into the RWJBarnabas Health system. We graduate 150 to 170 nurses a year at a time when there is a shortage of nursing personnel. Being part of a system offers those graduate nurses an opportunity to stay within the system instead of being scattered all over.

Ostrowsky: We currently have 900 openings in our system for nurses. No graduate from the Trinitas nursing program is going to go unemployed for more than three seconds—we have gotten graduates from this nursing school in the past and if I could do it legally I would insist that every graduate comes to work in our system! But yes, the nursing school is a great asset not just for us but for the entire industry, and we want to see that supported and hopefully expanded. In fact, I have actually discussed with the dean of the school, Roseminda Santee, what it would take to scale up.

EDGE: What other aspects of the merger stand out as “win-win” situations?

Ostrowsky: Trinitas has twelve Centers of Excellence that we will be able to learn from, including a specific focus on cardiac care, oncology, emergency services and, as we discussed earlier, wound care and behavioral health. That will help RWJBarnabas Health to scale several high-growth service lines, such as cardiology, oncology, neurology and orthopedics. I also see us benefiting from existing academic partnerships between Trinitas and Union County College, the College of St. Elizabeth and Kean University.

EDGE: This merger was finalized during a global pandemic. Did COVID impact the process?

Horan: The actual merger process, even during the COVID pandemic, went very smoothly. Obviously, meetings that normally would have taken place in a face-to-face setting were done virtually. But that was not as great an obstacle as it has been in other industries. Also, remember that Trinitas had been through this before, in 2000, when Elizabeth General and St. Elizabeth’s merged to form Trinitas Regional Medical Center. That was very tricky, but it became a model for consolidating a Catholic and non-sectarian hospital. That experience prepared us in some important ways for the merger with RWJBarnabas Health.

Ostrowsky: I think the way the teams came together to plan and execute our merger is a case study that’s worthy of being written up. There was incredible cooperation—a total of around 300 meetings between our staffs—and it shows in the results. Our alignment on the goals and the mission led to effective integration planning and execution. For me, this is a picture of what it looks like when you undertake a transaction like this and do it right.

That year Elizabeth played baseball with the big guys.

Karen Finkelstein

During the winter of 1872–73, Elizabeth caught an expensive case of baseball fever. The sport had long been popular in the city, which had grown to over 20,000 residents in the years after the Civil War. In 1870 and again in 1872, Elizabeth’s amateur baseball club, the Resolutes, had claimed the New Jersey championship. Their main rivals were in Jersey City, Newark and Irvington. The 1872 championship, the result of a 42–9 thumping of the Champion Club of Jersey City—along with rousing victories over some leading professional clubs—convinced supporters of the Resolutes to recruit a lineup of professional players in 1873 and join the National Association, forerunner of today’s National League. This would mark the city’s one and only season in baseball’s big leagues. Their competitors that year included teams from major cities: Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Brooklyn, and Washington, DC.

As insane as it seems to see Elizabeth on that list of “major-league” cities, the enthusiasm heading into the spring of 1873 was not entirely unfounded. Most experts considered the 1872 Resolutes the finest amateur team in the region, if not the nation. But baseball was still a very young sport and few teams had found a way to make the professional game profitable. Even the Boston Red Stockings, the National Association’s pennant-winners in 1872, were thousands of dollars in debt at the end of the year and sent some of their players home for the winter minus a final paycheck. The Resolutes hoped to solve this problem by forming a “cooperative” club. They would pay their expenses and salaries from their portion of each game’s gate receipts, collected from the city’s rabid baseball populace.

NJSports.com

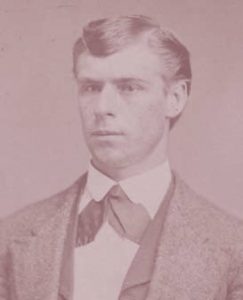

This was a fine idea on paper, but if you were a top player in 1873, would you play for a club that couldn’t guarantee your salary? If you said No way then you’re not alone. The Resolutes were laughed off by nearly every player they approached with this scheme. With no top stars interested in this proposition, the Resolutes cobbled together a roster of players from previous failed cooperative experiments, along with some local journeymen and a few better players who, unfortunately, were known as much for their surly attitudes and fondness for the bottle as their skills on the diamond. Those who did throw in with the club were encouraged by the fact that the team’s catcher, Doug Allison (above), was also the manager. The 26-year-old was the closest thing the Resolutes had to a “star.”

Catcher was the most important position on the field in the 1870s and Allison was one of the first players to move right up behind the batter to receive pitches on a fly instead of on a bounce, inviting the bat to cut through the air just a few inches from his face. A bit like NASCAR fans, Allison’s supporters came to witness his skill and daring, while also recognizing that a bloody accident was potentially just one pitch away. Another notable Resolute was a scary guy named Rynie Wolters, the first professional baseball player born in the Netherlands. Wolters had made a living in the 1860s as a cricket bowler and took up baseball pitching as the fortunes of the latter rose and the former faded. Despite the fact they served as Elizabeth’s opening day battery, Allison and Wolters were not what you’d call team players. They were baseball mercenaries and made no bones about it.

Filling out the lineup were Doug Allison’s brother, Art, along with Eddie Booth and Henry Austin—who formed the Resolute outfield—pitcher Hugh Campbell, and Favel Wordsworth, a shortstop with a name that seemed more appropriate for the stage than the diamond.

More than 500 fans braved chilly late-April temperatures to watch the Resolutes play their first official game, in Philadelphia. Wolters was horrible and they lost to their hosts, the Athletics, 23–5. Wolters stormed off and did not pitch again for Elizabeth, leaving Campbell to shoulder almost the entire pitching load the rest of the year. The Resolutes made a better showing in their second contest, falling to the Baltimore Canaries by an 8–3 margin, this time in front of 300 spectators.

Karen Finkelstein

Three areas of concern that cropped up almost immediately were that 1) the players didn’t seem to be gathering for practice between games, 2) because their home field did not have a dressing room, the player had to change into their uniforms in an Elizabeth rooming house, and 3) for some reason lost to history, the club was not actively advertising the date and location of its games.

Elizabeth was winless in May and, despite logging its first victory—over the Brooklyn Atlantics and their star fielder Bob “Death to Flying Things” Ferguson—barely drew flies for the club’s June meeting with the star-studded Red Stockings. Low attendance not only reduced the Resolutes’ basic operating capital, it also ate into the players’ “co-op” income, the combination of which triggered a slow, agonizing death spiral.