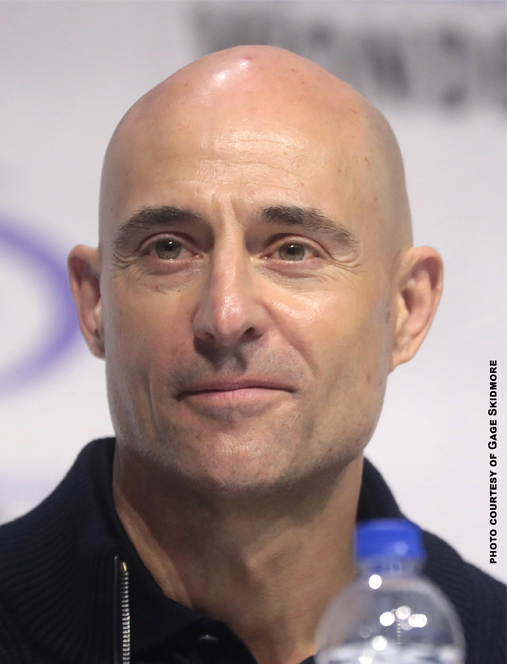

What have you been watching during the COVID-19 shutdown?

After finishing Tiger King, I sat down with my wife and sons and wrote a list of all the films they should have seen, and we’re working our way through those in my DVD collection after dinner. I wanted to introduce them to things like Being John Malkovich, old war moves like Where Eagles Dare, Lawrence of Arabia and Bridge Over the River Kwai. Also on the list is Tree of Life, Magnolia, Punch Drunk Love and Moneyball. We could never watch my own films—they would wonder what kind of narcissist I was.

What are you listening to?

I’m listening to a lot of podcasts, such as The Ballad of Billy Balls, which is set in the late-70s in New York and is about a girl’s attempt to discover a punk singer called Billy Balls. I’ve also been listening to Anton Lesser, who I played with at the Royal Shakespeare Company back in the 80s for Richard III. I also read the new Hilary Mantel novel, The Mirror and the Light.

What else are you reading?

I brought down a whole bunch of scripts to our little place in Sussex right on the edge of the Downs. I always find reading for pleasure diversionary and not as profound as something I’m going to be performing on stage. I did enjoy the coming-of-age story my wife wanted me to read, called The Art of Fielding, by Chad Harbach, about a college baseball player aiming for a national championship.

What do you miss the most?

I’m itching to get back to football with my friends in the garden. I play every Monday and Friday with the same guys I’ve played with for the last 17 years. I love the camaraderie and skill of six or seven a side. I’m missing it so much, because it makes my head feel right when I’m fit.

What will you be working on when things loosen up in the industry?

There will be another Shazam movie—people are realizing superheroes can be funny, which is good. I’m reading the script for Temple, as we are meant to be working on the second series. I’m going to be doing Oedipus next year with Hellen Mirren, so I read that every couple of days to try and let it get under my skin.

Editor’s Note: Mark Strong’s acting résumé includes unforgettable turns in Zero Dark Thirty, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Imitation Game and the two Kingsmen movies. He also stars in the British TV series Temple. This Q&A was conducted by The Interview People.

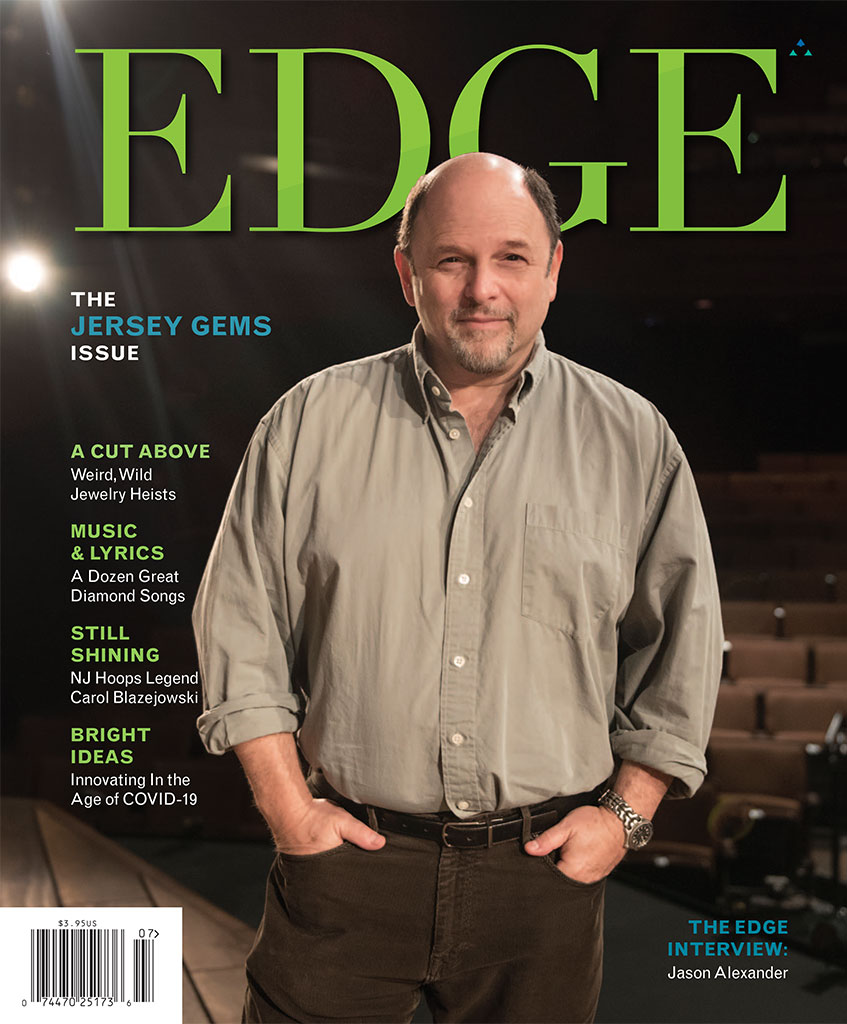

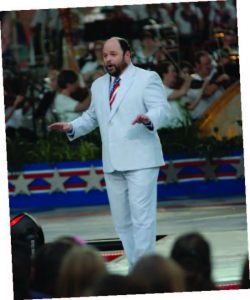

EDGE: You’ve been doing magic for a long time. Is that something that you look at as a hobby, or something that you would like to take to the public more often?

JA: Well, I will tell you that up until I moved to Livingston and fell in with those theater kids, magic is what I thought my life was going to be. I love magic and I really wanted to be a very good magician. I worked fairly studiously at it as a kid, I mean, as much as you can. Unfortunately, the kind of magic that I admire the most and wanted to do the most was the kind with cards and coins and small props. I’m not terribly good at it. My hands are not built for it and I think my personality was not built for the kind of discipline that it takes to get extraordinary at it. So, at age 12 or 13, I really was self-aware enough to know I wasn’t as good as I wanted to be, or needed to be, and that’s when theater sort of replaced that.

But I’ve always loved magic. I’ve been a member of the Magic Castle since I moved to Los Angeles, and I had a really interesting experience where the Castle was going through some difficult times financially. They asked if I would perform for a week, and I did an act that it took me three months to create. I was very proud of it. At the end of that time it, I won the award for Parlor Magician of the Year at the Magic Castle, which was a huge thing for me.

I will tell you, I have never been so frightened in my life as when I was performing that act. Everything has to go right. There is no room for a mistake. It’s really daunting.

If it goes wrong, you cannot save it with a funny ad lib. Yes, you can make it a better comedy moment, but you can’t make it a magical moment. So, it really is walking a tightrope. My friend, who performs under the name of Max Maven, is a mentalist magician. I was doing more or less a mentalism act at the Castle. At the end of my run there, Max gave me the greatest compliment anyone could ever give me. He said, “You know, if you wanted to be a lot less famous and a lot less wealthy, you could really do this.” [laughs] I knew exactly what he meant. I was very flattered.

So, I even bring magic to my directing work. We were in pre-production for a play that had four moments in it that, the minute I read the script, I went, “Well, these are magic tricks.” The creators and the production team didn’t realize they were magic tricks until I said, “Nope, this is a magic trick.” So, it informs a lot of what I do and how I think about performance. When I’m directing, it’s always there.

But I don’t think you’re going to see me touring with David Copperfield anytime soon.

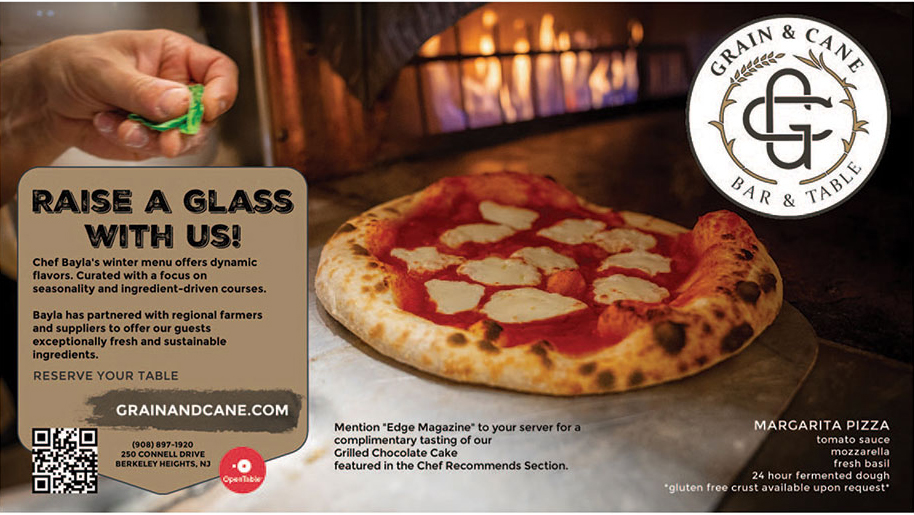

Grain & Cane Bar and Table • Maine Lobster Benedict

Grain & Cane Bar and Table • Maine Lobster Benedict

250 Connell Drive • BERKELEY HEIGHTS

(908) 897-1920 • grainandcane.com

Butter poached lobster, cage-free poached eggs and bernaise sauce. The flavors combine to create a beautifully silky dish that will be a weekend brunch favorite.

The Thirsty Turtle • Pork Tenderloin Special

The Thirsty Turtle • Pork Tenderloin Special

1-7 South Avenue W. • CRANFORD

(908) 324-4140 • thirstyturtle.com

Our food specials amaze! I work tirelessly to bring you the best weekly meat, fish and pasta specials. Follow us on social media to get all of the most current updates!

— Chef Rich Crisonio

The Thirsty Turtle • Brownie Sundae

The Thirsty Turtle • Brownie Sundae

186 Columbia Turnpike • FLORHAM PARK

(973) 845-6300 • thirstyturtle.com

Check out our awesome desserts brought to you by our committed staff. The variety amazes as does the taste!

— Chef Dennis Peralta

The Famished Frog • Mango Guac

The Famished Frog • Mango Guac

18 Washington Street • MORRISTOWN (973) 540-9601 • famishedfrog.com

Our refreshing Mango Guac is sure to bring the taste of the Southwest to Morristown.

— Chef Ken Raymond

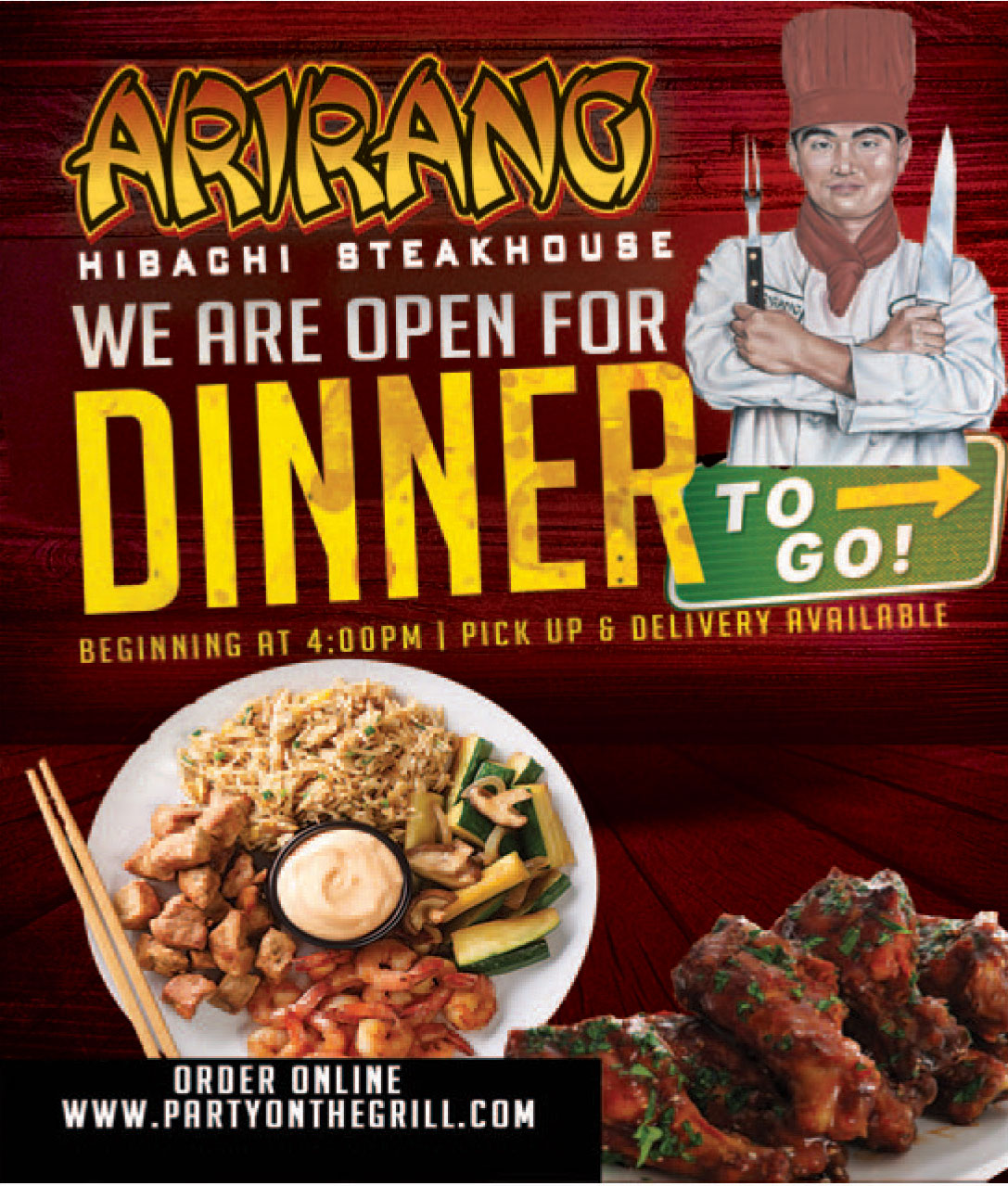

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Pork Belly Bao Buns

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Pork Belly Bao Buns

1230 Route 22 West • MOUNTAINSIDE

(908) 518-9733 • partyonthegrill.com

Tender pork belly, hoisin sauce and pickled cucumber served on a Chinese bun.

Daimatsu • Sushi Pizza

Daimatsu • Sushi Pizza

860 Mountain Avenue • MOUNTAINSIDE

(908) 233-7888 • daimatsusushibar.com

This original dish has been our signature appetizer for over 20 years. Crispy seasoned sushi rice topped with homemade spicy mayo, marinated tuna, finely chopped onion, scallion, masago caviar, and ginger. Our customers always come back wanting more.

Garden Grille • Beet & Goat Cheese Salad

Garden Grille • Beet & Goat Cheese Salad

304 Route 22 West • SPRINGFIELD

(973) 232-5300 • hgispringfield.hgi.com

Beet and goat cheese salad with mandarin oranges, golden beets, spiced walnuts, arugula, with a red wine vinaigrette.

— Chef Sean Cznadel

LongHorn Steakhouse • Outlaw Ribeye

LongHorn Steakhouse • Outlaw Ribeye

272 Route 22 West • SPRINGFIELD

(973) 315-2049 • longhornsteakhouse.com

Join us for our “speedy affordable lunches” or dinner. We suggest you try our fresh, never frozen, 18 oz. bone-in Outlaw Ribeye—featuring juicy marbling that is perfectly seasoned and fire-grilled by our expert Grill Masters. Make sure to also try our amazing chicken and seafood dishes, as well.

— Anthony Levy, Managing Partner

Outback Steakhouse • Bone-In Natural Cut Ribeye

Outback Steakhouse • Bone-In Natural Cut Ribeye

901 Mountain Avenue • SPRINGFIELD

(973) 467-9095 • outback.com/locations/nj/springfield

This is the entire staff’s favorite, guests rave about. Bone-in and extra marbled for maximum tenderness, juicy and savory. Seasoned and wood-fired grilled over oak.

— Duff Regan, Managing Partner

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Japanese Taco

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Japanese Taco

23A Nelson Avenue • STATEN ISLAND, NY

(718) 966-9600 • partyonthegrill.com

Choice of Tuna with wakeme, Kobe beef with sushi rice or Rock Shrimp with pineapple. Served in a crispy wonton shell, Asian slaw, topped with spicy mayo and teriyaki sauce.

Ursino Steakhouse & Tavern • House Carved 16oz New York Strip Steak

Ursino Steakhouse & Tavern • House Carved 16oz New York Strip Steak

1075 Morris Avenue • UNION

(908) 977-9699 • ursinosteakhouse.com

Be it a sizzling filet in the steakhouse or our signature burger in the tavern upstairs, Ursino is sure to please the most selective palates. Our carefully composed menus feature fresh, seasonal ingredients and reflect the passion we put into each and every meal we serve.

Support Our Chefs!

The restaurants featured in this section are open for business and are serving customers in compliance with state regulations. Many have created special menus ideal for take-out, delivery or socially distant dining, so we encourage you to visit them online.

Do you have a story about a favorite restaurant going the extra mile during the pandemic? Post it on our Facebook page and we’ll make sure to share it with our readers!

EDGE is not responsible for any typos, misprints or information in regard to these listings. All information was supplied by the restaurants that participated and any questions or concerns should be directed to them.

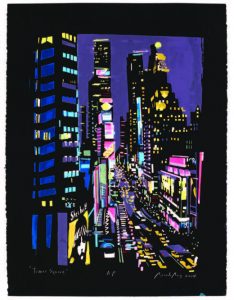

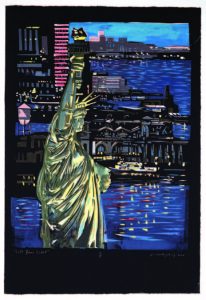

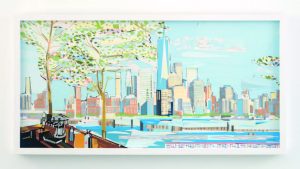

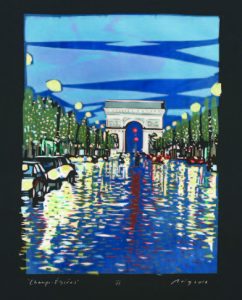

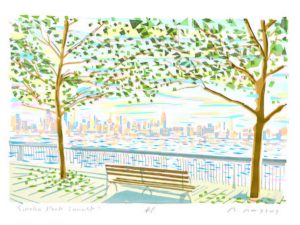

Seeing the world through an artist’s eyes can be the beginning of a transcendent experience. The work of Ricardo Roig adds a fascinating detour to that journey…along the fine edge of a master’s blade. In simplifying the boundaries of familiar imagery, Roig’s meticulous hand-cut screen prints reveal layers of complexity that seem new with each fresh encounter.

Wildflowers, 12″x12″ Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Times Square, 29″x43.5″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Lift your Light, 29.5″x42.5″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

New York City Dream, 44″x24″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Print

Roof Top Bar, JC, 41.5″x21.5″, Collage of Hand Cut-Paper Stencil Screen Prints

Champs Elysees, 24″x30″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Out East, 39″x23″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Sag Harbor (Boats), 30″x24″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Sinatra Park Sunset, 28.5″x20″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Rialto, 28″x21.5″, Hand-Cut Paper Stencil Screen Print

Ricardo Roig began his training at the Maryland Institute College of Art and then graduated cum laude from Kean University with a degree in Painting and Printmaking. He works out of two studio spaces, in Westfield and Hoboken, where recently he translated his unique printmaking process into three impressive outdoor stencil murals. Roig also has created murals for the interior walls of the new The Canopy Hilton Hotel in Jersey City and Hoboken’s W Hotel on River Street, where he also runs Roig Collection, a gallery for his work. Another large mural greets workers each day inside the Amazon warehouse in Woodbridge. Roig’s prints have been showcased in numerous galleries in the NY-Metro area, as well as the Hoboken Historical Museum and NYU Stern School of Business, which commissioned his work. “Art is my meditation and expression,” says the 36-year-old Roig. “Drawing with my knife gives permanence to the moment and provides me with a peaceful escape into a world of vivid color and abstracted shapes. In this imaginative mind state, I can explore and channel my own aesthetic.” Roig adds that he feels renewed as he meticulously crafts each layer, knowing that he will be creating something completely new and “offering people something different and inspirational to see and enjoy.” Ricardo Roig can be reached by email through his web site, which includes much more of his personal story and vision: RoigCollection.com.

Role of Ambulatory Surgery becomes more vital as Covid-19 subsides

By Yolanda Navarra Fleming

The numbers are tricky to pin down as Covid-19 cases rise and fall from coast to coast, but it appears that at least a third of Americans put off needed healthcare in the first four months of the pandemic. That figure covers everything from scheduled tests and screenings to minor procedures to actual emergency room visits. Caution is never a bad thing, but fear—especially fear fueled by a lack of accurate information (or sometimes way too much of it)—can exert a powerful influence on our decision-making. Often to our own detriment.

As Trinitas worked to stay a step ahead of the coronavirus this past spring and deliver a high level of healthcare to those who needed to be admitted, another part of the hospital—the Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC)—was closed and waiting to safely reopen, and is now firing on all cylinders. “Ambulatory” in the case of the ASC reflects its Latin root (abulatore: to walk). The ASC is an outpatient facility that allows our clients to have same-day procedures. Although there is always some risk in any type of surgery, the layer-upon-layer of Covid-19 precautions that have been adopted, as Trinitas doctors learn more about the virus, has minimized the risk of contracting and spreading the virus in the main hospital as well.

As Trinitas worked to stay a step ahead of the coronavirus this past spring and deliver a high level of healthcare to those who needed to be admitted, another part of the hospital—the Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC)—was closed and waiting to safely reopen, and is now firing on all cylinders. “Ambulatory” in the case of the ASC reflects its Latin root (abulatore: to walk). The ASC is an outpatient facility that allows our clients to have same-day procedures. Although there is always some risk in any type of surgery, the layer-upon-layer of Covid-19 precautions that have been adopted, as Trinitas doctors learn more about the virus, has minimized the risk of contracting and spreading the virus in the main hospital as well.

“Our Ambulatory Surgery Center provides an optimal environment for our patients and their families, as we do not treat Covid-19 patients in this facility,” says Donna Leonard, Peri-Operative Managing Director. “The atmosphere there is warm, calm, and peaceful. The ASC staff is professional, knowledgeable, and empathetic, in addition, our equipment is state-of-the-art. An important consideration when choosing an ASC site is knowing that we are a hospital-based facility, and all of the resources of Trinitas Regional Medical Center are at our disposal at any time, for any reason.”

The doctors, nurses, and technicians at the Ambulatory Surgery Center are skilled and experienced in a wide range of specialties and outpatient procedures. The ASC Operating Room handles:

- General Surgery

- Laparoscopic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Plastic Surgery

- Gynecological Surgery

- Ear/Nose/Throat Surgery

- Pain Management

- Orthopedic Surgery

More complex procedures are performed in the Main Operating Room at Trinitas, where the same rigorous cleaning and sanitizing procedures take place. These procedures include all of the above in addition to the following:

- Robotic Surgery

- Total Joint Replacement Surgery

- Genito-Urinary Surgery

- Ophthalmic Surgery

- Complex ENT Surgeries

Both OR areas are staffed by Board Certified Anesthesiologists, all nursing personnel are certified in Basic Life Support (BLS), they also have or are working towards becoming Advanced Cardio Life Support (ACLS) certified. Many Trinitas RNs are bi-lingual and multi-lingual. Most Registered Nurses have their Bachelor’s degree or are currently in a program working towards obtaining a BSN. We have several RN’s with BSN’s who are now Master’s degree holders in Nursing, and several more currently pursuing this highly regarded professional degree.

The $5.2 million 9,500 square-foot Ambulatory Surgery Center opened in 2014. Since then, more than 10,000 patients have been treated there.

The $5.2 million 9,500 square-foot Ambulatory Surgery Center opened in 2014. Since then, more than 10,000 patients have been treated there.

“It’s only natural to have a little fear where medical care is concerned, especially given the current environment,” says Leonard. “The medical community has expressed concern that necessary testing and procedures have been delayed due to the fear of being exposed to the virus if they choose to come to the hospital. The ASC center has taken and continually updates all precautions to keep our patients and staff safe. We confidently state that we are offering a safe environment for the return of patients to our facility.”

Editor’s Note: The Thomas and Yoshiko Hackett Ambulatory Surgery Center at Trinitas is part of the hospital’s main campus at 225 Williamson Street in Elizabeth. For more information, visit njambulatorysurgery.com.

When Covid-19 hit, Trinitas hit back…with a true team effort.

By Yolanda Navarra Fleming

You don’t have to be in healthcare to comprehend the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gary S. Horan, President & CEO of Trinitas Regional Medical Center, says it’s been unlike anything he has experienced in his many years in healthcare administration. As he details, Trinitas staff members met the challenges of the patient surge in the spirit of skill, compassion, and innovative teamwork.

EDGE: How has Trinitas Regional Medical Center adapted to the “new normal” conditions created by the COVID-19 pandemic?

GH: It was a challenge we didn’t expect but were prepared for, partly because Trinitas is no stranger to innovation. Innovation is the key in responding to something as novel as the COVID-19 pandemic. We had to get creative about a lot of things, including making additional space for COVID patients during the surge. We have taken every precaution to keep our population safe, including patients, staff members, and the outside community.

EDGE: How did the staff handle the surge?

GH: Well, prior to the surge, we activated our Emergency Command Center, which is staffed by senior administration, safety personnel, and infection-prevention personnel. Meetings and institution-wide conference calls were held every day to address the many issues that we knew were coming up. It was and still is a very volatile time, but saving lives is our business. We have such a dedicated, well-rounded, and fearless staff, who are not focusing on the negatives. But they needed help. As part of the Heroes Helping Heroes initiative, we were fortunate enough to have 20 registered nurses from Centura Health in Colorado come to Trinitas to assist in our efforts. They were extremely helpful in our Emergency Department and the Medical/Surgical units for more than four weeks.

EDGE: With a decline in the number of cases, do you expect another surge?

GH: There is certainly the possibility of another surge, but it drastically depends on how people behave in the upcoming weeks, and whether or not they observe the safety precautions. If people choose not to wear masks, use proper hand hygiene, follow the guidelines of social distancing, and avoid crowds, I’d say another surge is likely. If it comes to that, we are prepared and will do our best to carry out the Trinitas mission, just as we did the first time around.

GH: There is certainly the possibility of another surge, but it drastically depends on how people behave in the upcoming weeks, and whether or not they observe the safety precautions. If people choose not to wear masks, use proper hand hygiene, follow the guidelines of social distancing, and avoid crowds, I’d say another surge is likely. If it comes to that, we are prepared and will do our best to carry out the Trinitas mission, just as we did the first time around.

EDGE: In the meantime, what do you say to people who may be staying away from the hospital because they’re afraid to return?

GH: The fear is understandable, but unwarranted. We use advanced technology as part of many steps to disinfect the entire hospital. We were an early user of the Surfacide Disinfection UV-C system. This technology uses ultraviolet light to sterilize surfaces after they’ve already been wiped down with bleach. We’re asking our community to not neglect their health by putting off elective procedures and diagnostic testing because they think it might be unsafe to come to the hospital. It’s actually one of the safest places to be at the moment because of this technology and our attention to the matter.

GH: The fear is understandable, but unwarranted. We use advanced technology as part of many steps to disinfect the entire hospital. We were an early user of the Surfacide Disinfection UV-C system. This technology uses ultraviolet light to sterilize surfaces after they’ve already been wiped down with bleach. We’re asking our community to not neglect their health by putting off elective procedures and diagnostic testing because they think it might be unsafe to come to the hospital. It’s actually one of the safest places to be at the moment because of this technology and our attention to the matter.

EDGE: How has the pandemic affected your organization as a whole? Is there such a thing as a “silver lining” in this environment?

GH: I think so. The fact that Trinitas is a Catholic teaching hospital means that we possess a strong sense of faith as an institution. In spite of the challenges we’re facing, we are grateful for the ways we had to rise to the occasion. So, I would say a silver lining is seeing a great team spirit to fight and win against this pandemic.

Dan Lipow May Be Foraging at a Meadow Near You

By Andy Clurfeld

Right now, Dan Lipow is talking chanterelles. Don’t stop him. You’ll miss the opportunity to learn more about the princess charming of wild mushrooms than if you’d had an encyclopedia on the fruiting body of a fungus implanted in your brain while you slept. Because no tome on wild mushrooms—or most anything else that grows in the wild—can pinpoint for you the precise locations where such not-so-buried treasures lie like Dan Lipow can.

Ok. Chanterelles. This could be a great summer for chanterelles. As well as for, Lipow says, day-lily flower buds, purslane, wild ginger, elderberry, garlic scapes and sea beans. But you’re stuck on mushrooms?

“Local log-grown shiitakes, chicken-of-the-woods, milky cap mushrooms, lobster mushrooms—and more!”

“Makes me hungry,” Lipow adds.

Dan Richer, multiple-time James Beard Award-nominated chef of Razza Pizza Artignale in Jersey City, might say Lipow is always hungry.

“I’ve known Dan Lipow since 2006, 2007,” Richer says. “His love for food has kept evolving and intensifying. Fact is, my success has a lot to do with Dan’s support.”

Russell Farr, a soccer coach who lives in Morristown, hears the name “Dan Lipow” and immediately exclaims, “The ramps! The fiddleheads! The nettles! Dan’s selection is more than unique. It’s led me to a lifestyle. I started going to the farmers’ markets just to talk with him.”

Arirang

www.istockphoto.com

So who is this maestro of the meadows, the scavenger of the streams through the woods, the lord of the locavores? And what is The Foraged Feast, his burgeoning enterprise that, in short order, united the best foragers here in New Jersey with foragers in other prime-source parts of the country in order to bring wild things safely into home kitchens of the Garden State?

For someone who appears to live a kind of swashbuckling existence of thrashing out into territories less-than-tamed, Dan Lipow is warm and friendly, welcoming and inclusive, a natural teacher and a deep believer in connecting novice to expert.

He’s a good dude.

Born in New York City, raised in Connecticut and lucky enough to have a relative with a farm where he first encountered wild things, Toddler Dan was enthralled with the berry patch in his own suburban backyard.

Grain & Cane

www.istockphoto.com

“It was a mature patch, red raspberries and blueberries, and I used to pick the berries. A lot of berries,” he says. “My parents put in a vegetable patch. They put in a row of asparagus—we grew all sorts of stuff.”

A nearby apple orchard, trips to Long Island Sound for fishing, and “big, really big trees—there must’ve been morels there, with those big, old trees” occupied his time and mind. His family moved to Greenwich, and soon Teenage Dan was eyeing “massive oysters that we’d pop open” and “digging steamers and quahogs.”

Flash forward. He didn’t go to college right after high school, but strapped on a backpack and took off for Europe. It was 1987 and he was 18. “In Greece, a big gyro was 25 cents. All the stuff I ate there, I wouldn’t’ve eaten here. I hit 13 countries, going by ‘Let’s Go,’ ” the budget-friendly travel guides.

He returned to the U.S., worked in photography and went to Boston University for a year “so I could get into the Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara, California.” Three years there taught him much about California cuisine and even more about Mexican foods.

Soon, he was a sought-after photographer in New York City, traveling the world—and eating its cuisines. “I’d have an assignment, three weeks in Tokyo, for instance, and carte blanche for meals.” By the time Lipow was 30, he’d been to dozens of countries and “experienced food everywhere.”

He spent five months in Southeast Asia on a project of his own creation through the United Nations Human Rights Council. In consort with Habitat for Humanity, he documented issues in children’s habitats, the conditions, the realities. He presented his work at a U.N. conference in the mid-1990s.

“Hard work and great food,” he now recalls.

But by the end of the 20th century, he’d met his culinary-adventuring dream:

A giant Puffball. A mushroom that can grow to the size of, say, a basketball.

A friend who knew of Lipow’s prowess in the kitchen said, “You’ve got to Iron Chef this thing.”

“I went to the Whole Foods in Chelsea and stocked up,” Lipow says. “I cooked and cooked with that Puffball. Roasted. Made stock. Sir-fry. Cubed it—sugar plum and pepper balm. That giant Puffball opened the door. It could make magic.”

Soon Lipow was tutoring himself in mushroom studies. He was also studying foraging, and going for hikes in New Jersey, Connecticut, upstate New York.

“I was good at identifying mushrooms, and bringing them back home and using them. I was taking it all very seriously; I’d suck up the information.”

Meanwhile, Lipow and his wife decided in 2005 to move to Maplewood, where he was even more clearly able to see and experience the seasons and the cycles of what grows in the wild.

“You don’t see that in New York City,” he says.

He began to realize he was a true forager, understanding what edible treasures were right there, if not in plain sight, at least able to be unearthed by the knowledgeable eye.

www.istockphoto.com

“Knowing that about a forest is very powerful—knowing where the chanterelles exist. I want to find those [treasures] in that environment, understand the sense of place, the environment, the possibilities.”

He found his perfect world, “a world where you can’t stop learning.” And what he discovered in New Jersey is “its many, many terroirs; it’s not like everywhere else. There are lower and upper reaches, hillsides, valleys. Here in Maplewood, we sit in the Watchung Range. Sussex County has terrain a lot like Appalachia. Glaciers came down to just north of I-78.”

www.istockphoto.com

Soon a sign in the window of Arturo’s in Maplewood attracted Lipow’s attention: “Home-cured duck prosciutto.” That sign was written by its then-chef/owner Dan Richer, who was splicing authentic regional Italian dishes into the old pizzeria’s menu. Kindred spirits in more than first name, the Dans started collaborating.

Says Richer: “Dan taught me where the ramps are. When garlic mustard is in season. What Japanese knotweed is.

Back when farm-to-table what not yet a thing, I learned how exciting a walk in the woods with my friend could be. He brought these things to my menu—and they bring joy to people’s meals. It’s all so special.

“When Dan was considering transitioning from photography to foraging, well, I thought that was a no-brainer. I just told him to bring it to me, and I’d cook with it.”

A new career was born.

“I’d show up with wild maitakes and we’d roast them in Dan’s pizza oven at Arturo’s,” Lipow recalls. “I’d find things, I’d call him, and he’d say, ‘Bring them over!’ We’d then go in for tastings he’d make just for us.”

Those tastings, Richer says, expanded from private to reservation-only Saturday nights. Then a second tasting night was added. Indeed, on the basis of those resolutely original, hyper-seasonally focused tasting menus, Richer was nominated for a James Beard Rising Star Chef Award.

Lipow found other chefs willing to follow the forager along uncharted paths in the Garden State. By 2016, The Foraged Feast was rocking at a half-dozen farmers’ markets in New Jersey, and Lipow was working with other four-star foragers “as an aggregator… of the best-quality foraged and cultivated mushrooms,” as well as seasonal foraged fare such as those cherished sea beans, ramps, spring onions, spiky Devil’s Club Shoots, green briar tips, Juneberries, and what to some is pesky knotweed, but to Lipow is easily broken down by stovetop cooking until it caramelizes to pure deliciousness.

Courtesy of Dan Lipow/The Foraged Feast

He’s caught the attention of revered chefs, including Justin Antonio of Summit House, who “purchases mushrooms from him all year long” and makes spotlight dishes that include “his wild watercress, which I puree and serve with grilled calamari, preserved lemons, his ramps and his fiddleheads. I use his maitakes in a salmon dish, with fermented Napa cabbage, and I also roast his maitakes with pastrami spice. He challenges us all the time. No one I’ve ever met has more knowledge of his product than Dan Lipow.”

Melissa Goldberg of Short Hills, the founder of the Farm & Fork Society CSA, is another fan who uses his mushrooms in virtually everything she cooks: “Omelets, tarts, soups—if I’m cooking, and Dan’s mushrooms are in my kitchen, I throw them in! Have you had the velvet pioppini?” She pauses to exhale. “In a tart? With pasta? He opens people’s eyes to the world of mushrooms. He has such a connection to the Earth.”

One recent night, Dan Lipow is talking about his culinary colleagues at Garden State Kitchen in Orange, where he has his warehouse and often mingles with artisans preparing foods for market. He’s talking about the chefs he forages for, the customers who are now friends, the satisfaction he gets from sharing food and stories.

“Food can get staid and boring if you don’t experiment,” he says. “But there’s inspiration all around.”

He takes a (rare) breath, then continues: “It’s always about looking for that great morsel—that morsel that someone makes into that perfect bite.

“You know, I’ve got these great porcini. I shaved them, drizzled with lemon juice and extra-virgin olive oil. Sea salt, black pepper. It was so— I’ll send you a photo.” EDGE

Editor’s Note: Dan Lipow is on Facebook and Instagram through www.theforagedfeast.com. He can be reached at The Foraged Feast through email: theforagedfeast@gmail.com.

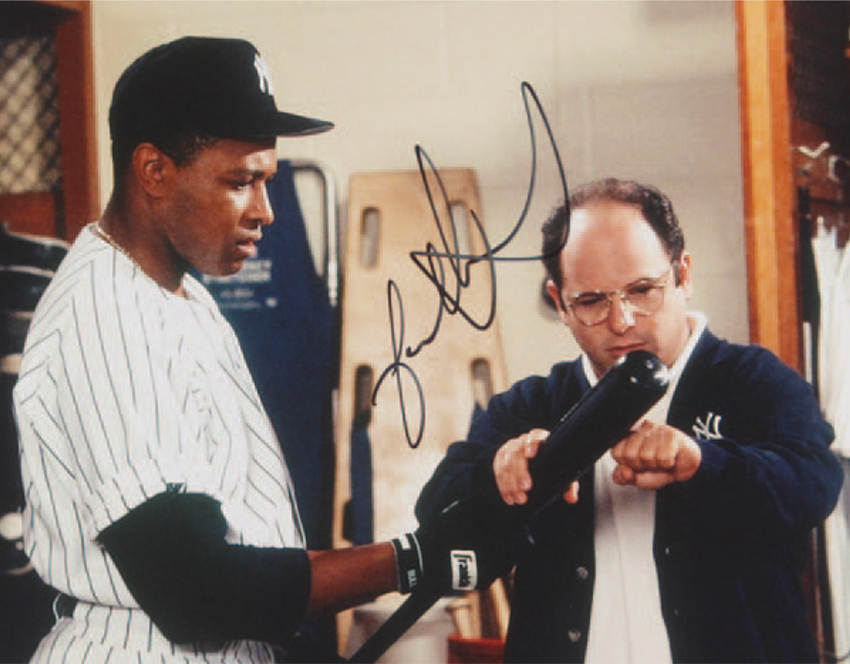

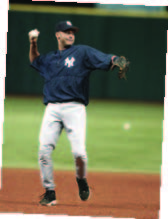

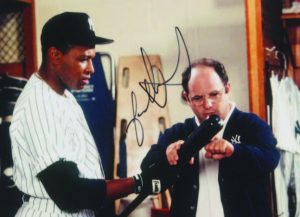

As the MLB season reboots, here are a dozen things to know about baseball in New Jersey.

The roots of baseball run deep in the Garden State. You may know that the first officially recorded game was played in Hoboken in 1846, and have probably seen the Currier & Ives print a few times, but for most people, that’s about it. New Jersey, in fact, has played a long, complex, inspiring, diverse, often messy, and surprisingly important role in the evolution of the game. Here are 12 fascinating facts that provide a rough idea of New Jersey’s place in baseball history…

1 Seven players who were either born or grew up in New Jersey have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame:

Upper Case Editorial

Mike “King” Kelly (Paterson) in 1945; “Sliding” Billy Hamilton (Newark) in 1961; Leon “Goose” Goslin (Salem) and Joe “Ducky” Medwick (Carteret) in 1968; Monte Irvin (Orange) in 1973; Larry Doby (Paterson) in 1998 and

Upper Case Editorial

Derek Jeter (Pequannock) in 2020.

2 In 2016, American Leaguers Rick Porcello (Chester) and

Rob Tringali

Mike Trout (Millville) became the first New Jerseyans to win baseball’s two top awards in the same season. Porcello won the A.L. Cy Young Award and Trout was the A.L. Most Valuable Player.

3 In 1972, Maria Pepe pitched three games for a Hoboken team before Little League Baseball threatened to revoke the entire league’s charter. The National Organization for Women (NOW) funded a lawsuit that resulted in all Little League chapters allowing girls to play.

Fritsch Cards

4 New Jersey produced several star players in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, including pitcher Dolores Lee, who went on to become Jersey City’s first full-time female police officer. After learning that she was being paid less than the JCPD’s minimum salary, she prevailed in one of the state’s first high-profile sex discrimination cases.

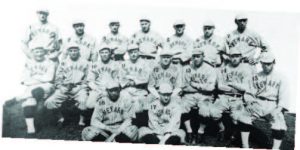

5 During the 1930s and 1940s, the Newark Bears were the top farm team of the New York Yankees. The Bears won eight International League pennants in 13 seasons. The 1937 Bears are considered by many experts to be the greatest minor-league team of all time.

6 The Newark Eagles of the Negro National League were we co-owned and operated by Effa Manley in the 1930s and 1940s. Manley was the first woman enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Upper Case Editorial

7 Paterson’s Hinchliffe Stadium, built-in 1932, is the lone remaining venue in New Jersey where Negro League baseball games were regularly played. It was the “home field” of the barnstorming New York Cubans and New York Black Yankees.

Four Star Productions

8 Seton Hall University became the Pirates in 1931 after an 11–10 comeback win over Holy Cross. A sportswriter described the team as a “gang of pirates” and the name stuck. Among the many stars who played for Seton Hall was Hall of Famer Craig Biggio and Chuck Connors, aka TV’s Rifleman.

Upper Case Editorial

9 In 1915, New Jersey fielded its one and only “major league” team, the Newark Peppers of the Federal League. The Peppers were owned by oil magnate Harry Sinclair.

Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum

10 In 1887, the Newark Little Giants of the International League signed catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker, one of the best African-American ballplayers of the 19th century.

11 In 1875, Joe Mann, a student at Princeton, pitched baseball’s first recorded no-hit game, against Yale. Mann used a curveball learned from future Hall of Famer Candy Cummings.

D. Benjamin Miller

12 Four New Jersey teams have won the Little League World Series: Hammonton (1949), Wayne (1970), Lakewood (1975), and Toms River East (1998). Future All-Star Todd Frazier led off the 1998 championship game with a homer and was the winning pitcher.

Are these the best-ever “Diamond” songs?

In the hands of a world-class jeweler, a diamond can be transformed into a thing of enduring beauty. As these songs show, in the hands of a great performer, a diamond can become a timeless masterpiece of an entirely different kind.

Delta Music Entertainment

Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend

Marilyn Monroe

Just about every big-name songstress has taken a crack at this iconic tune, which was originated by Carol Channing in 1949 for the Broadway smash Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Marilyn Monroe did perhaps the most famous version for the 1953 Technicolor film of the same name. More recently, Nicole Kidman sang it in Moulin Rouge! Ethel Merman, Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt, Emmylou Harris, Janet Jackson and Beyoncé also recorded it and, of course, Madonna borrowed liberally from Marilyn’s version for the “Material Girl” video.

Robert Balser/United Artists

Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds

The Beatles

The Beatles and, later, Elton John made this song one of rock n roll’s all-time megahits. The psychedelic cover of the 1967 Sgt. Pepper album and the song’s initials LSD led to suspicions that it was a “drug song.” John Lennon insisted that it was inspired by a drawing his son Julian had brought home from nursery school. A little-known fact is that Lennon played guitar and sang background on John’s 1974 version.

United Artists

Diamonds Are Forever

Shirley Bassey

James Bond fans wince when they talk about this 1971 contribution to the 007 franchise (Sean Connery kind of mailed it in), but there’s nothing not to like about Shirley Bassey’s sultry rendition of the film’s theme song. It was her second Bond theme—she also sang “Goldfinger”—and she would also sing a third time for Moonraker in 1979.

Diamond Girl

Seals & Crofts

The soft rock duo of Jim Seals and Dash Crofts scored a monster hit in 1972 with “Summer Breeze” and followed it up a year later with “Diamond Girl,” a Top 10 hit on three different Billboard charts. The chorus Diamond Girl…you sure do shine is one of those lyrics that gets stuck in your head for decades.

RCA

Diamond Dogs

David Bowie

The title cut from David Bowie’s bleak, dystopian 1974 album, “Diamond Dogs” is the story of Halloween Jack, who lives atop a Manhattan skyscraper. The guitar-heavy song was not a big hit, but it gained traction as the centerpiece of Bowie’s North American tour later that year and is now considered a rock n roll classic.

Harvest Records/Columbia Records

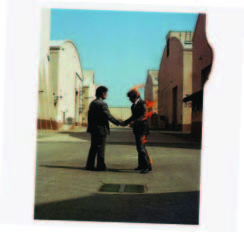

Shine On You Crazy

Diamond Pink Floyd

A favorite of Floyd fanatics, “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” was a tribute to Syd Barrett, whose declining mental state had led to a split with the band he had founded—and ultimately to his departure from the music business. The nine-part composition was part of the 1975 album Wish You Were Here and was accompanied by a trippy animated short created for the band’s subsequent tour.

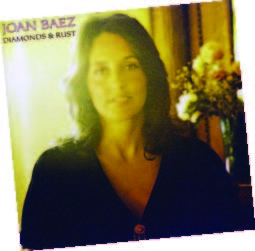

Diamonds and Rust

Diamonds and Rust

Joan Baez

The song recounts a phone call from a long-ago love, an “unwashed phenomenon” whom Baez later revealed to be Bob Dylan. “Diamonds and Rust” reached #5 on the Adult Contemporary charts and the album (of the same name) went gold in 1975. Baez fans count the song among her very best.

Warner Bros. Records

Diamonds On the Soles of Her Shoes

Paul Simon

Co-written with Ladysmith Black Mambazo founder Joseph Shabalala—and recorded with the group—“Diamonds On the Soles of Her Shoes” was not originally planned to be a part of Graceland. However, after Simon performed the song to wild acclaim on Saturday Night Live, it was added to the 1986 album, which went on to win the Album of the Year Grammy.

Diamonds and Pearls

Prince

The title cut from Prince’s 1991 album, which featured a holographic cover, “Diamonds & Pearls” was also the name of the singer’s 1992 international tour. The upbeat love ballad reached #1 on the Billboard R&B chart and was reprised by Alicia Keys and Chris Blue in the Season 12 finale of The Voice.

Diamonds

Diamonds

Rihanna

A standout cut from Rihanna’s 2012 Unapologetic album, “Diamonds” was a departure from the singer’s past hits about dysfunctional relationships, instead of exploring the meaning of love. The song was an international smash, topping the charts in the US, UK, and Canada—as well as more than a dozen European countries. Rihanna performed a stunning version of “Diamonds” on Saturday Night Live that November.

Editor’s Note: Did You Know… A song is now certified as “Diamond” if it is purchased as a download 10 million times. Free streams from services like Spotify also count: 1,500 streams are considered the equivalent of 1 paid download toward Certified Diamond status.

Editor’s Note: Did You Know… A song is now certified as “Diamond” if it is purchased as a download 10 million times. Free streams from services like Spotify also count: 1,500 streams are considered the equivalent of 1 paid download toward Certified Diamond status.

AJ Capella and Anthony Mangieri on summer, the shutdown, and the new normal.

By Andy Clurfeld

The world is a different place than it was at the start of this year, or even at the start of spring. Now, as summer dawns, it’s challenging to imagine what the traditional season of sun- and-fun capped by a lazy, long dinner at a favorite restaurant might bring. Restaurants? Some open, but differently; some closed, sadly permanently; most in a state of flux.

We speak to two acclaimed restaurant chefs, both New Jersey-born and bred and Garden State loyalists to their core.

Anthony Mangieri, nationally renowned and referred to as the Pope of Pizza, started his career in the early-, mid-1990s in a slip of a storefront in Red Bank, where he baked authentic Neapolitan breads. A few years later, he opened his first Una Pizza Napoletana in Point Pleasant Beach, before moving Una Pizza first to New York’s East Village, then to San Francisco’s Mission District, next back to New York, on the Lower East Side, and finally, home again, in downtown Atlantic Highlands. He is, rightly, credited with inspiring a new generation of pizzaiolos and showing pizza-eaters that his pizza, based on his otherworldly dough (starter born in 1996), is the original “transporting” pizza.

AJ Capella, a rising star in the culinary world, garnered respect and devoted fans during his turns at the Ryland Inn, Whitehouse Station; the Aviary in New York, and A Toute Heure in Cranford, before taking the top chef spot at Jockey Hollow Bar + Kitchen in Morristown. Now 30, he’s spent half his life working in restaurant kitchens and developing a style that marries the soul of authentic European peasant cookery with globally accented high-style finishes. Mangieri and Capella, each working and percolating these past months, take stock and reflect, refresh and predict.

Anthony Mangieri’s Una Pizza on Orchard Street, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, has closed completely during the COVID-19-induced pandemic; however, Mangieri had, on Feb. 28, opened his new Una Pizza Napoletana at 91A First Avenue in Atlantic Highlands. That Una Pizza has remained open, serving takeaway pizza Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Expanded hours are planned as restrictions on commerce ease.

Mangieri:

Dylan+Jeni

“This shutdown has given me time to reconnect. It’s a forced shutdown, but it’s given me more time with my family and to do things other than restaurant cooking.

“The issue is not so much the shutdown, but the reality of restaurants. What is that reality? For me, we’ve had to revert to minimal staff, which we can do and still do our pizza. But what is the reality for bigger restaurants with bigger staffs? The hardest transition at this time is for those restaurants.

“Do they go at half-capacity for six months? Most fine-dining restaurants will not come out of that. Elaborate menus need bigger staffs. I understand adapting to the time, but fine-dining take-away?

Dylan+Jeni

“I had no interest in doing take-away; it’s a different product. I’ve never myself had delivery (food), ever, and neither has my wife (Ilaria, who is from Naples and has a background in classical music and communications). The shutdown didn’t change my business model, my approach. I’ve had to limit ingredients, because I can’t now get some of them. I’m now using mozzarella made in New Jersey, from a company that imports buffalo mozzarella from Italy and makes it here.

“So I make the amount of pizza I can myself handle, about 90 pizzas a day, and that’s what I’ll do. We’ll be open four to five hours a day, and I’m toying with the idea of taking some reservations (if dine-in restrictions are eased) so I can control things.

“I get to work at 7, 7:30 in the morning, prep for hours, then make pizza the whole time we’re open, then clean up. It’s intense—the mental and physical focus. To open with outside tables—that would cost lots and lots of money: new tables, umbrellas, staff going in and out.

“Right now, I’m excited about the new ingredients I’ve got—pepperoni, peppers, great basil.”

Anthony Mangieri starts talking about the great jars of imported tuna he’s been tasting, then about chocolate, and ice cream, and gelato. The best ingredients lure him, inspire him and, inevitably, propel him to share them. Always have, always will.

Capella:

Jockey Hollow Morristown

“I was in Italy when this whole thing started. I was in Bologna, late February, Modena, having Lambrusco at a winery, tortellini en brodo everywhere, eating mortadella every day! Gnocchi frito—everywhere. It’s fried dough that expands and hollows out. Super-thin, filled with air. It’s served like a bread.

“We were eating a lot of a tangy, creamy farm cheese that’s spreadable, soft, with thick curds. I was talking to Sal (Pisani, a cheesemaker who operates Jersey Girl Cheese, and a friend of Capella’s) and he told me he’d work on making it here.

“Anyway, we got one of the last flights back. I quarantined; didn’t go anywhere, didn’t leave my house except to walk my dog. Then the shutdown.

“We cooked and cooked at home. My girlfriend is a pescatarian, so I don’t eat meat at my house. Cooking at home was fun, not rushed.

“Now, I don’t know about high-end dining, which is what I’ve always done. I don’t think it’s going to be back any time soon. Takeout, yes, doing online groceries, yes. I’m organizing all of that now at Jockey Hollow.

“But I’m also thinking, ‘What can I be doing differently? How can I reinvent, say, a fast-food sandwich? I’m thinking, say, crispy lamb neck instead of a chicken sandwich. ‘Cause high-end restaurants, if they have to cut back from doing 400 or 500 covers to 125 people, that’s not workable. You’ll have to do take-out plus a grocery in the basement.

Jockey Hollow Morristown

“I’m thinking, coming up with ideas. A 10-, 12-seat café for high-end dining, plus take-out. All locally sourced foods on the menu. A two-sided place. I think a lot of opportunity can come out of this pandemic, and the new post-pandemic restaurant models will change. The days of high-end dining as we know it are over.

“I’m thinking of a menu with scallop ravioli, with a whole scallop inside, poached, with compound butter, as the ravioli cooks. A smoked duck egg custard. You know, a riff on chawanmushi, Japanese steamed custard. But finish it with a tiny dice of Taylor ham, top it with cheese and egg. Classic New Jersey!”

Then AJ Capella talks through a menu for this new-restaurant dream that fuses the world’s cuisines with the Garden State culinary traditions and ingredients. His food always will have a heartfelt New Jersey accent.

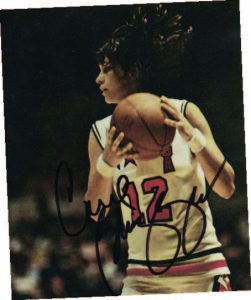

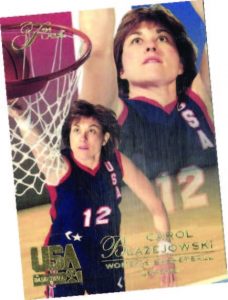

In the lexicon of basketball, “B.C.” has its own particular meaning: Before Carol. That’s because, for women’s basketball fans, everything that happened prior to the moment that Carol Blazejowski made her debut for Montclair State is ancient history. She not only brought a complete game to the floor, she brought a completely different one—pouring in layups and jumpers, suffocating opponents on defense, and finding open space and teammates where none seemed to be. In elevating her team and her sport, Carol also brought basketball fans out of their seats. She set a Madison Square Garden record with a 52-point game in 1977 and finished with more than 3,000 points in four varsity seasons. Born in Elizabeth and raised in Cranford, she is a Jersey Gem who actually played for the Jersey Gems! Mark Stewart talked to “The Blaze” about the twists and turns of life in basketball, and the ways in which she has tirelessly pushed her sport toward bigger and better things.

Upper Case Editorial

EDGE: When you were setting records at Montclair State, you were playing a three-dimensional, vertical game when most players in women’s basketball were still in a two-dimensional, horizontal mindset. How did you develop that approach?

CB: From a physical standpoint, I was very athletic, so that came naturally. I honed my skills against guys. You had to be sharp, you had to think ahead, so that led to my mental approach. I couldn’t compare to their strength or agility or size, so I had to become more cerebral to gain an advantage.

EDGE: What made you choose Montclair State?

CB: I really didn’t have many choices. Title IX was a law but no one was in compliance with it, so there weren’t scholarships. We had limited resources, I was lower-middle-income, so it was really about economics and also proximity—my parents could come and watch me. Montclair State had a relatively good basketball team at the time. Also, I was going to be a Phys Ed teacher and it was a teacher’s school.

EDGE: The New York Times, Sports Illustrated, and other media outlets really jumped on your story. How did that coverage change your life, and what did it do for women’s basketball?

CB: We were so good at Montclair State and the media really took notice. We were playing a national-level schedule and were part of the sports conversation in the metropolitan area. It certainly helped when we had that record-setting performance at Madison Square Garden, when all of the New York journalists were there. That really opened people’s eyes to, one, Wow women really can play and, two, people really wanted to watch women play—there were 12,000 people in the Garden that day. The writers took it and ran with it and I am very grateful for that. It was their voice that helped propel us and garner interest in the general public.

EDGE: Was there a lot of focus on the 1980 Olympics, for you and for the sport?

CB: Yes. I was the last player cut from the 1976 Olympic team, so that was fuel and motivation for me. It really inspired me during my last two years in college. Also, it was on the heels of the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid and everybody was so excited about the U.S. team’s hockey championship. Also, the 1976 Olympic women’s team had won silver—Russia was the team to beat, so there was a lot of build-up.

EDGE: You were in a tricky position at that time because of the amateur rules, which forced you to choose between the Olympics and joining the women’s professional league. You would have been its marquee star—

CB: Oh, yeah. Listen, I lost a lot of money over the years because of this silly rule with the AAU and non-professional. However, I was laser-focused on my goal of making the 1980 Olympics. No amount of money or anything else was going to change that. I figured if we won the gold medal, subsequently there would be other opportunities to benefit from that, both financially and with a job.

Fleer Corp.

EDGE: Every athlete has a moment that makes them want to put their fist through a wall. Was that moment for you when President Carter announced the U.S. Olympic boycott?

CB: Yes. That was true for all of us, not just the women’s basketball team. We’d sacrificed a lot—not just in money but in time and effort and commitment. Some people actually left school to go and train. The Olympics isn’t supposed to be political, and clearly it was.

EDGE: What was the experience like playing for the New Jersey Gems?

Upper Case Editorial

CB: The quality of the play was great. The game was very athletic. Our home court was the South Mountain Arena in West Orange. It was over ice and they never turned the heat on, so it was an interesting environment we played in. But, you know, these athletes—and I include myself—we would have played for nothing. It was professional ball, it was a chance to follow your passion, to mix your love with your work. I didn’t get paid the full amount of my three-year contract and of course, the league folded. But I wouldn’t have traded it for anything in the world.

EDGE: What did you do after that?

CB: I worked for Adidas. I really had two choices. I could go overseas and play, but at the time it wasn’t as lucrative as it is today. Or I could get a job. I had been affiliated with Adidas during my days at Montclair State and so there was an offer on the table to work in the promotional field. So that’s what I did for 10 years. I transitioned over to the NBA in the 1990s and did licensing, and then I worked with Val Ackerman to prepare the women’s team for the 1996 Olympics and, beyond that, for the WNBA.

EDGE: The 1996 Olympic team captured the public’s imagination. What was it about that team and the personalities of the players that made a pro league possible?

CB: People were hearing more about women’s basketball from a media perspective and more fans were coming to games and seeing superstars like Lisa Leslie, Sheryl Swoopes, and Rebecca Lobo, who were really generating a lot of recognition. The Olympics were in Atlanta, in the United States—it was the perfect storm, the perfect launchpad, if we won the gold medal, to launch the WNBA. The plan went accordingly. It was special.

EDGE: You got involved with the WNBA New York Liberty right from the get-go—

CB: When New York announced that they would have a WNBA team, Ernie Grunfeld and Dave Checketts called and I became the GM.

EDGE: What was the most rewarding aspect of running that team? And fair warning, I’m going to ask you the other half of that question.

CB: [laughs] I enjoyed the fact that women were getting a chance to play professional basketball. The joy and commitment they had was special. I really enjoyed going to the arenas and seeing the fans come out welcoming and embracing the sport. And it wasn’t just female fans. It was men, it was dads, it was a whole cross-section of society. That, to me, was very rewarding. And, of course, winning. You can’t leave out winning! It was about having one of the premier franchises in the league and also being very successful.

EDGE: Back then I got to know Coquese Washington of the Liberty a little bit, who graduated from Notre Dame and was working on her law degree. I realized how smart and well-educated the players were. That’s not necessarily the first thing you think when you look at an NBA roster—Hey, I wonder if he was a chemistry major?.

CB: Listen, I had every belief that the WNBA would be successful, but the reality was that there were a lot of doubters. These women knew they had to plan for the possibility that there might be no league. They had to get their degrees. And they did just that. They were wonderful human beings, wonderful players, very inspirational, great role models, very competent, and capable on and off the court.

EDGE: What were the challenges of running a professional sports franchise for 14 seasons? What kept you awake at night?

Courtesy of Carol Blazejowski

CB: There were two “boxes” that were always foremost in my head. There was the box office, which meant how much revenue came in. And there was the box score, which meant how many wins. There is constant pressure when you run a team but, playing in a famous arena, there is even more pressure to be successful.

EDGE: After the WNBA, you came back to Montclair State and also started work on the Blaze Hoop Crew.

CB: Yes, I returned to my alma mater and work there for almost nine years, not in the athletic department but on the business of the college—marketing, communications, events, community relations. I left back in December. I really felt a void of being in the gym, a void of being in sports, and a void of being with kids. And I love basketball. I formalized Blaze Hoop Crew about five years ago and now I do it on a full-time basis. We do basketball programming and instructional services. It’s not AAU, it’s not camps, it’s not leagues. I’ve been involved in clinics and camps my whole life, but this is more about fundamentals. We go from kindergarten all the way up through high school, but really our sweet spot is kindergarten through the grammar school age group. We work with girls and boys to give them an appreciation for the game.

EDGE: So where are we now in the evolution of women’s sports?

CB: We have closed the gap in terms of the equity between men’s and women’s basketball, and in life in general. I think we’re moving forward, but we need to understand that there is more to be done so we can really prosper. I’m proud of what we’ve accomplished and now it’s the new generation that has to take it to the next level. I’m happy to see the strides that we’ve taken. And believe me, in the 40 years since I graduated Montclair we’ve made a lot of strides. But we still have a long way to go. I’m a big supporter of all sports on the women’s side, not just basketball. It’s my responsibility and I’ll continue to do that.

EDGE: I have to ask…which players remind you of you?

CB: There are a lot of players in the WNBA right now that I really admire. If I had to pick two players, on the men’s side it was always Larry Bird. I loved watching him play. He was a fierce competitor who hated to lose. On the women’s side, I look at Diana Taurasi. A lot of people call her cocky but I call her confident. She can do it all on the floor, she’s cerebral, and she’s not afraid to put a team on her back and accept the pressure of getting it done.

Editor’s Note: For more information on the Blaze Hoop Crew, visit blazehoopcrew.com or email info@blazehoopcrew.com.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Drywall*

*BUT WERE AFRAID TO ASK

By Jim Sawyer

www.istockphoto.com

Drywall giveth and drywall taketh away. If you’ve ever had to build a new structure, add to one, or repair one that’s old or damaged, you probably understand the myriad advantages of using drywall. Relative to traditional construction and plastering techniques, drywall is inexpensive, light, safe, and requires far less expertise to install. And when it comes time to knocking something down, drywall is just as quick, easy, and inexpensive.

The disadvantages of drywall? It is easily damaged, it can be tricky to repair, it doesn’t do much to baffle sound or to insulate and, if it gets wet, well, there’s that nasty mold issue. In areas of the country (including our own) where floodwaters have inundated homes constructed with drywall, the result is almost always a gut job. Left to mold, a drywall home can quickly turn into a lung-choking teardown. By contrast, older historic homes featuring traditional plaster just need a basic hose-down after a flood; a splash of paint and they are good to go. No mold. No problem.

So it’s a trade-off. But on the construction industry’s big balance sheet—where the speed of construction and demolition can make the difference between a big profit and a razor-thin one—drywall is a no-brainer.

That certainly accounts for the tens of billions of square feet manufactured in North America each year. Say what you will about the ups and downs of the housing market in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, but the population of this continent continues to boom and people need places to live. So until some better material comes along, drywall is here to stay.

WHAT IS IT?

WHAT IS IT?

Drywall goes by many names: wallboard, plasterboard, and sheetrock among them. Whatever you call it, there isn’t a whole lot of science to drywall. It typically comes in a 4’ x 8’ sheet, usually 3/8” or 1/2” thick, encased in paper or a paper-pulp material. Thinner sheets are sometimes used to negotiate curved surfaces. Drywall is attached with special screws to wood or metal studs, and sometimes glued as well (especially on ceilings).

The white-gray material sandwiched between the paper is gypsum. Among its many qualities, gypsum is inherently fire-resistant. In addition, some drywall products come impregnated with glass fibers in order to further slow the spread of flames and smoke. Local building codes usually require that this type of board—which is 5/8” thick—be used in furnace rooms and garages, or homes heated by wood stoves.

Structures prone to flooding (either by Mother Nature or from plumbing or roofing mishaps) or in high-humidity areas are often built with mold-resistant or moisture-resistant drywall. Note the use of the word “resistant.” It does not imply mold- or moisture- “proof.” Mold-resistant boards are treated with a special coating and generally do not have paper, which is a favorite home of fungus. Contractors typically use mold-resistant drywall in bathrooms and kitchens. Sometimes this material is called “greenboard,” which technically is incorrect. Greenboard is slightly different (although it can be used in the same situations); it performs best in high-humidity areas of a home, such as a laundry room or damp basement.

What should you do if drywall is no longer dry? Tear it out and replace it. What if you detect mold? Do not dither, especially if someone in your home or workplace is allergic to the spores. The drywall should be replaced and the mold remediated. There are obviously professionals who do this, but an Internet search can show you ways to do it yourself. Proceed with care and caution. As with many dangerous organisms, the mold you see isn’t always the stuff you need to be most concerned about. If moisture has entered the back of a sheet that has been primed and painted, it has already had a lot of time to grow and spread before you start breaking it up. In these situations, trust your nose over your eyes—you’ll be able to smell the mold before you see it. And keep in mind that tearing it out is likely to release spores back into the environment and possibly into places it hadn’t been before, such as your HVAC system.

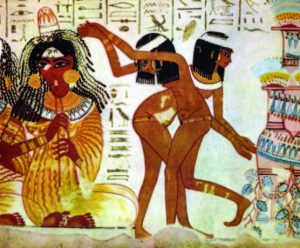

The British Museum

WHO INVENTED IT?

Now that the basics are out of the way, how about a little history? The use of gypsum as a wall material dates back more than 3,000 years. It is easy to get out of the ground, simple to process, and holds colors really well.

It was quarried for plaster in ancient Egypt in the Old and New Kingdoms—in 2017, archaeologists identified one quarry on the east bank of the Nile that measured three square kilometers. The ancient Egyptians discovered that gypsum could be ground into a fine powder and mixed with water to produce a bright, durable skim coat of plaster that could hold paint extremely well on interior walls in homes, temples, and tombs. Thousands of years later, it still looks great. The mineral owes its name to the ancient Greeks, who used it in much the same way. Gypsos actually means “plaster” in Greek.

www.istockphoto.com

Gypsum or lime were used more or less interchangeably as a component in plaster in the ensuing centuries. One of the most famous sources of plaster was in the Montmartre section of Paris, hence the name Plaster of Paris. The French like to say there is more Montratre in Paris than Paris in Montmartre.

They’re speaking literally in this case—the gypsum and lime deposits there were used in plaster and paint in the city for centuries. In the hands of French artisans, it was made to look like wood, metal, and stonework when those materials were either too cumbersome or expensive, or just unavailable.

US Gypsum

The process by which gypsum becomes plaster has remained relatively unchanged. It is heated to about 300 degrees, until the moisture is released and it becomes a dry powder—which is then reconstituted with water to be applied or shaped as needed. Gypsum being a mineral, it has other uses, too. For example, it was used in colonial America to improve soil quality; Ben Franklin was a huge proponent of this particular use, which reduced runoff and delivered additional nutrition to plants. In the early days of Hollywood, shaved gypsum was sometimes trucked in to mimic snow. Although gypsum is used in the manufacture of Portland cement—making up two or three percent of the mix—it is not what makes sidewalks sparkle (that’s mica). In case you’re wondering, Portland cement gets its name from the Isle of Portland, on the southern coast of England, not from Portland ME or Portland OR.

Getting back to drywall, the world’s first “wallboard” factory actually opened in England, in 1888, in the English town of Rochester, about 30 miles east of London on the River Medway. The Industrial Revolution was shifting into high gear and an alternative to traditional lath-and-plaster construction for interior walls intrigued British homebuilders: Wallboard used far less wood and required limited plastering expertise, and also avoided the weeklong drying process of traditional plastering. In addition, it could be put up in a poorly heated environment, which was a Godsend in England with its cool, damp climate (and historic issues with central heating). By the 1920s, it was the material of choice in most new construction in the UK.

In America, the plasterboard revolution came a bit later, and shifted into high gear during the post-WWII building surge. The first drywall factory in the U.S. dates back to around 1900, in upstate New York. According to the web site gypsum.org, the product was initially favored because of its fire-resistant properties and featured multiple layers of gypsum (which was cheaper and more plentiful than lime plaster) sandwiched between two pieces of wool-felt paper. In 1917, US Gypsum Corp. debuted “Sheetrock,” the now-familiar single, non-layered sheet of gypsum plaster completely encased in paper, which could be joined with smooth, even seams. At the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago, several building were constructed almost entirely of Sheetrock, which was a huge marketing coup.

By the Baby Boom years, when more than 20 million new homes were constructed in America, drywall was the cheap and easy workaround for traditional plastering. It has continued on as the material of choice for new homes, renovations, home repair projects—you name it.

FEMA

WHAT IS “CHINESE” DRYWALL?

In the seven decades that drywall has been widely available to homebuilders and homeowners, the domestic supply has had no problem keeping up with the demand, as gypsum is plentiful and easy to process in North America—until the early 2000s, that is. You probably remember the housing boom, but do you also recall that no fewer than nine major hurricanes smashed into Florida in the span of two-plus years, and then Katrina inundated New Orleans in 2005? Demand for drywall soared and caught North American manufacturers by surprise. With the supply low and prices high, many builders in the Southeast turned to a new source: China.

Unfortunately, drywall factories on the other side of the Pacific were focused on production and profitability rather than safety, and as a result, countless millions of square feet of defective or contaminated product found its way into American homes. The first sign that something was wrong came in the form of complaints by homeowners that exposed copper surfaces were turning black and “ashy.” Also, new refrigerators and air conditioners (which contain copper coils) were malfunctioning.

New West Gypsum Recycling

This made people wonder what was happening to their copper pipes and wiring—and they were right to wonder. The cheap drywall was giving off volatile gases, including hydrogen sulfide, which corrodes copper and also created health issues that included a range of upper respiratory problems. By the time the problem was identified, the tainted drywall had been used in somewhere between 50,000 and 150,000 homes; no one can say for sure because much of the product bore no markings that could be traced back to a specific manufacturer. One manufacturer that did pop up fairly often was Knauf, a Tianjin-based company with a deceptively European-sounding name. Some estimates put the amount of Knauf drywall unloaded in New Orleans and various Florida ports at close to a billion pounds between 2003 and 2009. In the aftermath of this debacle, a New Orleans court ruled that homeowner’s policies had to cover the remediation of contaminated drywall. The IRS also provided tax relief for people who suffered property damage because of the tainted product.

www.istockphoto.com

They Did What?

While the substandard Chinese drywall flooded the market in the mid-2000s, domestic drywall producers—who had been ramping up production since the late-1980s—doubled down and invested heavily to further increase their output. Consequently, the deflation of the housing bubble in 2008–09 devastated the industry. North American drywall companies were suddenly stuck with huge supplies and withering demand. Many were in no shape to wait for the economy to rebound.

All was not lost, however. As the housing market receded, a growing number of builders, flippers, and rehabbers began snapping up cheap properties and foreclosures and demand for drywall began to creep up again. However, contractors noticed a rise in cost on drywall at a time when it should have been bargain-priced. This was accompanied by an inexplicable reluctance on the part of manufacturers to compete on price. Obviously, since the manufacturers could not boost profits by increasing volume, they had to raise their prices.

There is nothing illegal about this…unless they plan to do it together. Which, apparently, they did. The result was a class-action suit against eight companies near the end of 2012 that ended with a nine-figure settlement. It wasn’t the first time drywall companies had been slam-dunked by the courts; price-fixing litigation dates back to the 1920s in North America.

WHERE ARE WE NOW… AND IN THE FUTURE?

We are in good shape. Today, the drywall supply is safe and sound—which is good to know in an era of increasing environmental sensitivity. Unused sheetrock scraps can actually be recycled, keeping thousands of tons out of landfills each year. Also, a steady demand for installation provides jobs for millions of people who do not have traditional construction skills, creating an entry point into an important trade. The retail price in New Jersey for drywall is $10 to $20 for a 4’ x 8” sheet (depending on type and quality) and another $50 or so per sheet to install professionally, including labor, supplies, and equipment.

Since you’ve made it this far, you are probably wondering, “What’s in the future for drywall?”

I’m so glad you asked.

The industry is aware that its product is somewhat problematic in the climate-change picture, in that it does not insulate particularly well. A new material called ThermalCORE, developed by the German chemical company BASF and National Gypsum, a U.S. company formed in the 1920s, could be a game-changer for builders and consumers. The new drywall material is impregnated with tiny wax beads encased in plastic shells. During the day, the wax melts and absorbs heat. At night, the wax hardens, releasing the stored heat.

Builders in Europe have been testing a version of this technology and it has demonstrated an ability to reduce energy bills by as much as 20 percent. The cost of using ThermalCORE in a typical home in New Jersey would probably raise its construction cost by $5,000, which would be recouped in about five years.

Classic jewel heists…from the historical to the hysterical.

By Mark Stewart

Last November, a pair of thieves in Germany made off with a group of priceless artifacts from the Green Vault Jewelry Room in Dresden’s Royal Palace. When asked to actually put a price on the haul, experts estimated the value of the theft at over $1 billion, making it the largest caper of its kind in history. Three sets of 18th-century jewelry were taken, each including dozens of precious gems. The theft was an old-school “hack”—the thieves smashed through the museum showcases with an ax.

The lure of gems and jewelry has proved irresistible to scores of get-rich-quick criminals over the centuries, dating back to tomb-robbers in ancient Egypt (and perhaps farther back than that). No less alluring to the rest of us are the details of these crimes, particularly the most imaginative ones…and sometimes the most unimaginative ones. Here are some of my favorites:

United Kingdom Government

1671 • NOBLE GESTURE

The “Holy Grail” of thievery targets might just be the Tower of London, which has housed the British royal family’s crown jewels for centuries. One of the loopiest schemes to make off with them was concocted by Thomas Blood, who spent a great deal of time and money creating a fake identity so he could pass himself off as an English nobleman. Blood befriended Talbot Edwards—the official Keeper of the Jewels—and promised that his rich nephew would wed Edwards’s as-yet unmarried daughter, elevating both into high society. Since they were practically related, Edwards agreed to give Blood and some fake-noble buddies a private viewing of the king’s bejeweled crown and scepter. Once in the inner sanctum, they knocked out Edwards, broke up the crown and scepter with a mallet, stuffed the pieces down their pants and ca-chinged down to the bottom of the tower—where they were immediately apprehended by the guards. Blood expected to lose his head, and probably should have, but when King Charles II heard the story he couldn’t stop laughing. He rewarded the counterfeit noble for his chutzpah with a genuine title and a country estate in Ireland.

American International Pictures

1964 • MURPHY’S LAW

One of the legendary party animals of the 1960s was Jack Murphy, aka Murph the Surf, a concert violinist, tennis pro and national-champion surfer who lived for the next adrenaline rush and had absolutely no impulse control. He also was known to help himself to the odd piece of jewelry to finance his hedonistic lifestyle. One evening while passing the American Museum of Natural History in New York, Murphy noticed that a number of gallery windows on the building’s top floor were cracked a couple of inches for ventilation. He knew this gallery very well: It housed the J.P. Morgan Collection of gems and minerals. On the night of October 29th, Murphy and two accomplices scaled the outside of the castle-like structure, entered the gallery and discovered to their delight that the alarms on the cases all had dead batteries. They helped themselves to gemstones by the handfuls, including the Star of India (the world’s largest sapphire) and climbed back out the window completely unnoticed. The theft, discovered the following morning, was a national sensation. Murphy and his pals upped the ante on their partying, arousing suspicion, and were arrested at their hotel three days later. They had already sold several diamonds, including the famed 16.25-carat Eagle Diamond, which was never seen again. Free on bail, Murphy was rearrested for robbing Eva Gabor and later convicted of a Florida murder. In 1975, he was the subject of the movie Live a Little, Steal a Lot, starring Robert Conrad and Don Stroud. Murphy was paroled in 1986 and became an ordained minister.

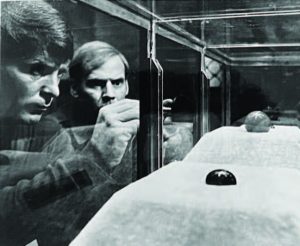

1989 • DUST DEVIL

It is common knowledge among thieves that members of the Saudi royal family diversify their oil wealth by stashing away significant quantities of high-end gems and jewelry. Kriangkrai Techamong, a Thai gardener working at the palace of a Saudi prince, scaled the outside of the building, jimmied open a cheap wall safe, and helped himself to 200 pounds of loot (which included a blue diamond the size of an egg). He hid his booty in the dust bag of a vacuum cleaner, which he wheeled calmly past the prince’s security team and out of the palace. Techamong shipped the jewels to himself before boarding a plane back to Thailand. The fencing part of the operation was not as well-thought-out, however. Some of the unique pieces started showing up in photos of Thai politicians and their spouses, prompting the Saudis to send a trio of investigators to Thailand. All three were murdered.

www.istockphoto.com

2003 • REALITY BITES

In a heist worthy of Ocean’s Eleven (or Twelve, or Thirteen), a highly skilled team assembled by criminal mastermind Leonardo Notarbartolo successfully ran a gauntlet of security systems and made off with over $100 million in gold, jewelry and precious stones from a vault two stories beneath the Antwerp Diamond Center in Belgium. Operating out of a small office they had rented in the building, the thieves made copies of master keys, conquered a lock with millions of possible combinations, evaded an array of motion and heat sensors, penetrated an 18-inch steel door and swapped security tapes on their way out to erase video evidence of their crime. Notarbartolo, who managed to fence the bulk of his booty, was shocked when the authorities quickly cracked the case and arrested him—even though they never did figure out how he did it. The clue linking him to the crime was DNA recovered from a half-eaten salami sandwich. No more spoilers here—J.J. Abrams optioned the story so one day you’ll see the whole thing on the silver screen.

2008 • TUNNEL VISION

The Academy Awards are “showtime” for the world’s top jewelers, and Italian design group Damiani is no exception. Workers in the company’s Milan store were preparing for an Oscars party when seven men dressed as police officers inexplicably appeared on the other side of a sophisticated security system, scooped up $20 million in jewelry, and disappeared down a staircase, never to be seen again. The thieves had spent weeks in the basement of the adjacent retail space, which was unoccupied, tunneling through a wall that was nearly 30 feet thick. Fortunately for Damiani, its best items had already been shipped to the U.S. and were adorning the necks of celebrities gliding across the red carpet.

2012 • EASY RIDERS