5 Minutes with …

Naomi Ackie

Was it challenging to play an iconic person like Whitney Houston in I Wanna Dance with Somebody?

What I realized, and this helped to put everything into perspective, was that she was only human. She was amazing in part because she was only human and achieved that much. To me, true empathy when it comes to working on something like this is to go, Yes, she had one of the most amazing voices in the world. But she was just as human as I am. Whitney had as many conflicts as I do, as many arguments with herself, as many problems as anyone else. In that context, it then didn’t become a challenge—it actually became like a dance between me and my imagined Whitney. And as soon as you kind of take people off of a pedestal, when you take people and you ground them, it becomes so much easier to do your job.

How did you prepare for and research the role?

I had coaches for dialect and movement. But I actually overdid it when it came to research. I watched every single one of Whitney’s videos on YouTube countless times, and it became like a prison. Funnily enough, that’s not usually the way I roll. Like, I’m pretty relaxed when it comes to prep for work. But this took a toll on my mental health. I had to take a break from the script and Whitney for about a month.

Was there added pressure playing a non-fiction character?

Yes. I’ve been thinking about this recently…so, you know, there’s the normal stuff: learn the accent, how her lips move around a song, what she physically looks like, how she presents herself. But there was also managing my anxiety around what I want to create and what I think other people want to see. That was a real tussle for me, because there is this kind of struggle about being a people-pleaser when you’re a performer. And I constantly had to be reminding myself, Tell the truth of the story. It shouldn’t be perfect. This is an affectation, you are pretending. So allow yourself the freedom to do that. That was a lesson that I learned two weeks before we finished [laughs]. It’s hilarious to me. I’m like, God, I wish I knew that right at the top!

Do you worry about any backlash from American actors as a British person playing an American of color?

Yes and no. I think there are not enough parts for black people and people of color in general. So really the problem isn’t with me playing Whitney, the problem is with the higher-ups not investing in the right places. As a black woman, being in this industry, I am going to [irritate] some people. They might be white, they might be black, they might be both, they might be anyone else. I am going to do things that upset people, but I can only follow my instinct—and trust that when people hire me, they’re not hiring me because I’m British or whatever it is, they’re hiring me because I offer a service, I’m good at my job and I have integrity. Am I worried? Yeah, but I’m trying to do this thing where I don’t worry about what people think about me anymore.

Editor’s Note: This Q&A was conducted by Lucy Allen of the Interview People.

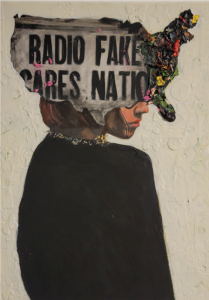

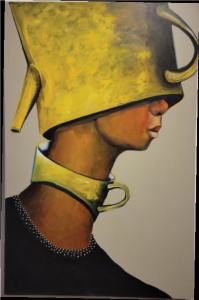

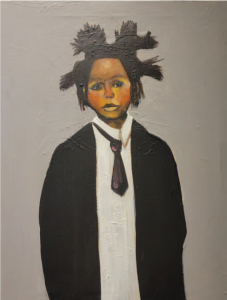

Artists often create works reflecting their strong objections to profoundly troubling world events. Iconic case in point: Picasso’s Guernica, painted in 1937, blatantly revealed his anger and sorrow for Hitler’s unprovoked bombing that destroyed the politically inconsequential town of Guernica in Spain. Today, much artwork speaks to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, the rejection of Roe v. Wade by many states, and the storming of the Capitol building on January 6th. Art can be powerful enough to move viewers’ concepts of the destruction perpetrated by people about whom Jesus reportedly said, “They know not what they do.” The art of Julia Rivera offers her viewers an intellectual and undeniable plea for the bad to stop trying to ruin the good.

We The People • 40” x 36” • Mixed Media

Be The Exception • 40” x 36” • Mixed Media

Our Breathing Is A Fragile Vessel 24” diameter • Mixed Media on Wood

Just Breathe • 24” diameter • Mixed Media on Wood

Green Country • 28” x 18” • Mixed Media on Canvas

Defeated on Principle • 24” x 18” • Mixed Media on Canvas

Don’t Tell People Your Plans 36” x 40” • Mixed Media on Canvas

Always Make Them Wonder 20” x 30” • Oil on Canvas

Basquiat • 11” x 10” • Oil on Canvas

It Is Not Our Difference 41” x 22” • Mixed Media on Wood

About the Artist

Born a Puerto Rican in the Bronx in 1965 and now a resident of Freehold, Julia Rivera says, “I have become a political artist… Our democracy is designed to speak the truth.” Through her staunch desire to portray endangered people, particularly women and children, Rivera’s heady message is balance, peace, and survival. Also an art restorer, she attended Escuela de Artes Plasticas in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and the Studio Arts College International in Florence, Italy, where she earned a master’s degree in 17th-century painting and restoration. One of her recent solo exhibitions, titled Intersectional, was featured at the DETOUR Gallery in Red Bank. Her paintings and sculptures are in numerous permanent collections, including in the United States, China, France, and Puerto Rico. Piece by piece, Rivera’s exceptionally riveting works inspire and combine beauty, perspective, and hope for important change.

—Tova Navarra

EDGE takes you inside the area’s most creative kitchens.

Sonny’s Indian Kitchen • Sonny’s Butter Chicken

Sonny’s Indian Kitchen • Sonny’s Butter Chicken

225 Main Street • CHATHAM (973) 507-9462/9463 • sonnysindiankitchen.com

Sonny’s butter chicken is one of the best, delicious, smooth buttery and richest among Indian curries. It is made from chicken marinated overnight and baked in a clay oven then simmered in sauce made with tomatoes, butter and various spices.

— Chef Sonny

The Thirsty Turtle • Pork Tenderloin Special

The Thirsty Turtle • Pork Tenderloin Special

1-7 South Avenue W. • CRANFORD (908) 324-4140 • thirstyturtle.com

Our food specials amaze! I work tirelessly to bring you the best weekly meat, fish and pasta specials. Follow us on social media to get all of the most current updates!

— Chef Rich Crisonio

Common Lot • Wagyu Beef Tartar

Common Lot • Wagyu Beef Tartar

27 Main Street • MILLBURN (973) 467-0494 • commonlot.com

Our wagyu beef tartar is paired with a Singapore style pepper sauce, summer herbs and flowers and sea beans.

— Head Chef/Owner Ehren Ryan

Trattoria Gian Marco • Short Rib Rigatoni

Trattoria Gian Marco • Short Rib Rigatoni

301 Millburn Avenue • MILLBURN (973) 467-5818 • gianmarconj.com

Our Short Rib Rigatoni is a perfect winter dish! Slow cooked short rib, wild mushrooms, imported rigatoni and pecorino romano.

— Chef Genero

440 Parsonage Hill Road • SHORT HILLS (973) 467-8882 • par440.com

Linguine with baby clams, mussels, calamari, scallops, shrimp and fish of the day in tomato sauce.

— Chef Pascual Escalona Flores

Galloping Hill Road and Chestnut Street • UNION (908) 686-2683 • gallopinghillcaterers.com

Galloping Hill Caterers has been an incredible landmark for over 70 years. We pride ourselves in delivering “over the top” cuisine, impeccable service and outstanding attention to detail. That is the hallmark of our success! Simply, an unforgettable experience. Pictured here is one of our crepes flambé that really creates lots of excitement!

— George Thomas, Owner

Limani Seafood Grill • Seared Sea Scallops

Limani Seafood Grill • Seared Sea Scallops

235 North Avenue West • WESTFIELD (908) 233-0052 • limaniseafoodgrill.com

Day boat large sea scallops served over sun dried fig, Marsala wine and caramelized granny apples with sauté baby spinach and Belgian baby stemmed carrots.

— Chef/Owner George Vastardis

Welcome Back!

The restaurants featured in this section are open for business and are serving customers in compliance with state regulations. Many created special items ideal for take-out and delivery and have kept them on the menu—we encourage you to visit them online.

Do you have a story about a favorite restaurant going the extra mile during the pandemic? Post it on our Facebook page and we’ll make sure to share it with our readers!

EDGE is not responsible for any typos, misprints or information in regard to these listings. All information was supplied by the restaurants that participated and any questions or concerns should be directed to them.

The Cooperman Barnabas Burn Center team makes the state’s toughest cases its business.

RWJBarnabas Health

The relationship between humans and fire is an old and complicated one. Controlling fire and fearing it are both baked into our DNA. Few thoughts are more terrifying than the prospect of being trapped by flames; the pain generated by a severe burn is unimaginable to all but the unfortunate few who have experienced it. How firefighters and people who work near intense heat do what they do is incomprehensible to most of us. That being said, roughly 1 in 700 Americans will have to be admitted to an emergency room to treat a burn injury in 2023. One in 10 of them will be admitted to the hospital—often with life-threatening third- or fourth-degree burns.

In New Jersey, the most severe cases end up in the hands of the doctors and medical staff at the Cooperman Barnabas Burn Center in Livingston—New Jersey’s only state-certified burn treatment center. The Burn Center has 12 beds in its intensive care unit and another 18 beds for non-ICU cases. As three-quarters of serious burns are accidental, there is no “typical” patient at the Cooperman Barnabas Burn Center. Which is why the facility is ready and able to treat anyone from an infant to a geriatric admission.

About 400 to 500 patients are treated annually at the Burn Center, which is recognized by the American Burn Association and American College of Surgeons for the optimal care provided by the dedicated team of multidisciplinary medical professionals. The team is headed by two accomplished surgeons: Medical Director Michael Marano, MD, and Associate Medical Director Robin Lee, MD.

The Burn Center has been in operation for 45 years, but it gained national attention in 2008 with the publication of Pulitzer-nominated After the Fire: A True Story of Friendship and Survival by Robin Gaby Fisher. The book chronicled the recovery of two teenage students who were badly burned in the deadly fire that swept through a freshman dorm at Seton Hall in 2000. Their cases still rank as two of the worst the Cooperman Burn Center had ever treated.

www.istockphoto.com

Aftercare

The increased survival rate of badly burned people has brought about a new set of issues that are being addressed at Cooperman Barnabas and other burn units around the country. Once wounds have healed and a patient is out of physical danger, for many the work has just begun.

The anxiety and depression that frequently accompanies physical recovery can lead to crippling PTSD and feelings of low self-esteem and social isolation that come as a result of visible disfigurement (especially to the head, face and neck).

Studies have shown that non-resolution of these issues can lead to chronic psychiatric problems; one study conducted through the National Institutes of Health in 2017 reported that 100% of burn victims experienced significant anxiety during their recovery and a “vast majority” demonstrated depressive symptoms. The study underscored the importance of sensitizing burn-ward staff members to the psychological needs of their patients.

Understanding Severity

www.istockphoto.com

Have you ever wondered, when reading that someone has suffered burns over, say, 20% of his or her body, how that number is determined? There is actually a chart that assigns numbers to different areas of the body for adults, obese adults, children and infants.

Doctors note the affected regions and start adding up the numbers. The anterior and posterior torso take up the most real estate—18% each in adults and 24% each in obese individuals.

Burn severity is measured in “degrees”—from first-degree to fourth. First-degree burns are superficial and the least serious. They can be caused by any heat source, including the sun. Though painful, they only affect the outer layer of skin (the epidermis). Second-degree burns involve the lower layer of skin (the dermis) and often cause blistering or swelling.

Third-degree burns reach deep down to subcutaneous tissue and destroy the epidermis and dermis, leaving charred or white skin. Fourth-degree burns are obviously the worse. They can affect muscle and bone and destroy the nerve endings in the burn area. Third-degree and above are considered “severe” and potentially life-threatening burns; often they call for skin grafts—one of the specialties of the Cooperman Barnabas Burn Center surgeons.

According to the American Burn Association, severe burns are credited with taking 3,400 lives in the US each year, with residential fires accounting for about 75% of fatalities. Inside that number, the ABA does not distinguish between deaths from burning and smoke inhalation. Vehicle fires, usually caused by a crash, claim around 300 lives a year. The remaining 500-plus burn deaths include everything from scalding to electrical burns to people who perish in wildfires.

www.istockphoto.com

Fear of Fire

The very natural and healthy human fear of being burned is different from pyrophobia, a debilitating fear of fire. Pyrophobia sufferers experience severe stress or panic attacks at the sight of a small flame or even the smell of something burning. They have been known to get dizzy at backyard barbecues and can become anxious when they overhear others talking about a fire.

Only a very small percentage of individuals suffering from pyrophobia have had a life-threatening or even dangerous experience with fire. Like many people who suffer from phobias, they acknowledge their fear is untenable, but that doesn’t make it any easier to overcome. Some studies suggest that pyrophobia runs in families—either it is learned or inherited. The most effective treatment strategy involves exposure therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, or sometimes both.

Physical Response

www.istockphoto.com

The human body is capable of miraculous feats of healing. However, it is not built to respond to severe burns. Burn injuries trigger the body’s inflammatory response—the reaction that fights off “invaders” ranging from viruses and bacteria to toxins and cancer cells. In the case of a deep or extensive burn, the inflammatory response can trigger a sudden drop in blood pressure, sending a victim into shock. It can also trap fluid inside the body. In either case, if vital organs (heart, lungs, kidneys, brain) do not receive the oxygen they need, they can go into failure and a burn victim Even when a burn patient is stabilized, the damage done to the skin—which is the body’s first line of defense against bacteria—can lead to infection and sepsis at a time when the immune system has been significantly compromised. A generation ago, the outlook for patients suffering burns over more than 50% of their body was bleak. Now it is not unheard of for people with burns covering 80% or more to pull through. Much of the progress can be credited to the myriad ways skin grafts are done, as well as a better understanding of the healing process for third- and can die. fourth-degree burn victims—including the roles played by nutrition, pain management, wound treatment and the battle against infection.

Of course, preventing burns and increasing awareness of how and when they are most likely to occur, are significant parts of keeping the public safe. To that end, the Cooperman Barnabas Burn Foundation supports a wide range of educational programs aimed at different constituencies, ranging from firefighters to healthcare professionals to schoolchildren.

Editor’s Note: The Cooperman Barnabas Burn Center is located at 94 Old Short Hills Road in Livingston. Like Trinitas Regional Medical Center, it is part of the RWJBarnabas Health System. The Burn Center offers a Firefighter Health & Safety Education course, a Standard Operating Guide, free lung cancer screenings and other resources to give firefighters the resources they need to manage their health.

A look at our beloved and indispensable shadow language.

www.istockphoto.com

Of all the everyday things humans use, nothing is more human than the use of slang. It is a tool wielded by every culture, subculture and sub-subculture that enables people to communicate clearly and confidently—without actually saying what they mean. As a bonus, slang doubles as a kind of membership card: If you don’t understand it, sorry, you’re not in the club. And while it can be mean-spirited, it is more likely to be funny, charming or silly. Sometimes, it’s all of these.

Straight fire, the theme of this issue, is slang for what past generations might have called radical. Or crazy good. Or, a century ago, the bee’s knees.

Bee’s knees, for the record, was a Prohibition cocktail made with real gin, real lemon juice and real honey. In other words, the absolute best. But wait. Before it was a drink, a bee’s knee meant something really tiny. Also, during the 1920s, the most famous dancer of the Charleston was a sexpot named Bee Jackson. Were Bee’s actual knees, exposed for all to admire, the absolute best? By the time the experts got around to answering this question, bee’s knees had been replaced by other superlatives, including cat’s pajamas. That’s another thing about slang. It is a creature of the moment, constantly changing, often for no reason other than change itself. What might be cool today is likely to be uncool a year from now, and then quaint, nostalgic and ultimately forgotten. Consider some common slang from the 1990s, when dinosaurs roamed the earth: Crunk, Fly, Buggin’ Out, Talk to the Hand—when was the last time you heard someone use any of these non-ironically? Social media has accelerated the spread of new slang and, as part of the same process, accelerated the demise of old slang. Honestly, sometimes it’s hard to keep up with it all.

NBCUniversal Television and Streaming

ESL Challenges

The misuse of slang offers an endless well of comic possibilities. Think of Steve Martin and Dan Aykroyd on the recurring SNL Festrunk Brothers skits from the 1970s. The two “wild and crazy guys” were hilariously confident in their tenuous grasp of American slang and it was funny because it was true. Learning American slang has long been one of the most challenging aspects of learning English as a second language, but also an absolute necessity. Master some key slang expressions, the thinking goes, and you’re likely to “blend in” sooner.

Dark Origins

Historically speaking, two things are almost certainly true about the use of slang: 1) the concept was invented by criminals and 2) it has always flourished in and sprung forth from cities. For countless centuries and, until relatively recently, people communicated face-to-face in public settings. That worked well unless you didn’t want others overhearing what you had to say. In towns and cities where meeting places tended to be crowded with eavesdroppers, it would have been difficult to plot or plan or coordinate nefarious activities. However, if the folks at the next table over had no idea what you were talking about, you could enjoy a level of security. Slang was a kind of verbal encryption.

Slang was also a neat way to prevent newcomers and outsiders from integrating comfortably into the culture of a town. Cockney rhyming slang raised this to an art form. It is possible to understand every word of a conversation between two East End Londoners and have no idea what they are talking about. “Bees and Honey” means money, “Fisherman’s Daughter” means water and “Rattle and Clank” means bank. And so on and so forth.

Interestingly, lexicographers are somewhat at odds regarding the origin of the word slang itself. It shows up in English texts in the late-1700s, but its roots may be Scandinavian. Some have traced it to the Norwegian word slengja, which refers to the use of abusive language. One of the tricky things about pinning down the roots of slang is that, almost by definition, it was spoken as opposed to being written down. That was true pretty much up until the advent of texting, Tweeting and social medial posts.

Staying Power

A quick Google search will turn up an endless number of lists of slang expressions that have fallen out of favor, changed meaning or blipped completely out of existence. Which makes one wonder which currently popular slang terms will have the staying power of classic words like Cool and which will go the way of Wisenheimer, Daddy-o and Knuckle Sandwich. I’m betting that Karen, Ghosted, Basic, Throwing Shade and Low Key will one day be dim memories.

Oh, and add Straight Fire to that list. If it hasn’t gone out of vogue in the two months since I turned in this story!

New owners of old homes are learning important lessons about fire prevention.

High demand. Low inventory. Over-ask bidding wars. Soaring prices. Roller-coaster interest rates. Whether you’ve participated in the New Jersey real estate market during the 2020s or just watched from afar, it has been something to see. The traditional home-buying process gave way to an out-and-out frenzy, with many purchasers ending up owning properties they hadn’t remotely considered when they first started out. In many cases, New Jerseyans found themselves moving into century-old (or older) homes without a full understanding of what they were getting into. In some cases, they were attracted by the charm and detail of historic structures. In other cases, newer (or fully updated) construction was financially out of reach. Sometimes, it was all that was available in their target area and in their price range.

www.istockphoto.com

Now they are coming to grips with the unique responsibilities involved in owning a vintage home, such as repairs, upgrades and general upkeep. Under-standing the fire-safety picture is one of the most important ones and, distressingly, also one of the most overlooked.

Historic properties are full of surprises, mostly pleasant ones. Among the most significant ones is that, if fire should break out, they actually tend to give occupants much more time to exit safely than newer construction. This may seem counterintuitive at first, but think about it: Their thick plaster walls and (typically) higher-quality materials and construction, can slow the spread of a blaze—or at least take longer to burn. Many newer homes have “safety times” of five minutes or less (sometimes as little as two minutes), which means that is how long you have to safely exit in a fire before your odds of survival begin to plummet. Older homes have safety times of 15 minutes of more, in many cases because they feature natural materials that burn relatively slowly and do not emit toxic fumes when ignited. Also, their ceilings tend to be higher.

“Higher ceilings can help in early smoke detector activation and notification to the resident to evacuate the home,” says Westfield Fire Chief Michael Duelks, CPM. “With higher ceilings it takes longer for smoke to bank down to standing height, which again helps the resident to evacuate early.”

A People Problem

www.istockphoto.com

What causes fires in historic homes? For the most part, the same thing that causes fires in brand-new homes: people. Roughly half of the 350,000 annual house fires in the United States have to do with cooking. They start in the kitchen or somewhere else where food is being prepared or served. The next culprit is heating equipment, most notably space heaters, at 13%. Smoking, which used to be a major cause of house fires, now only accounts for 5%—not because smokers have suddenly become more careful, but because there are far fewer of them. Indeed, more than 20% of home fire fatalities occur in blazes started by smoking materials.

Electrical fires make up almost 10% of household fires, and this is where owners of older homes need to be extra vigilant. It’s a catch-all category, of course, but it includes faulty and over-burdened wiring, which needs to be identified and addressed before you plug your entire entertainment system into a power strip—and then plug that power strip into a wall outlet.

An experienced house inspector is usually able to identify points of immediate concern. Some are obvious, like old-school knob and tube wiring (above right)—or another non-grounded system—which was fine for its time but not designed for today’s appliances. This is an item, by the way, that could cause your home insurance premiums to be much higher than expected because, when inadequate wiring is overloaded, it increases the chance that an arc fault will occur, which can create enough heat to start a fire inside a wall.

That charming 1920s bungalow only needed 30 or 40 amps worth of service when the first family moved in. You’ll probably use at least five times that amount. In all likelihood, previous owners upgraded the electrical capacity incrementally. That can be as much of a curse as a blessing. If some of that work was shoddy or is just wearing out, it can be really difficult to catch in an inspection. It becomes incumbent upon the new owner to be aware of some signs that this might be a problem—for instance, if the same circuit breaker keeps clicking off, or your lights are flickering. And, of course, if you detect a strange “burning” smell but can’t quite figure out where it’s coming from, that’s not good. One option for new owners of old homes is to have an electrician install circuit interrupters. Circuit interrupters detect an abnormality in how electricity is moving through your house and interrupt the circuit.

www.istockphoto.com

Gray Area

Part of the appeal of buying an old house is the realization that, in some ways, no one truly “owns” a historic structure. You’ll just be taking care of it for the next family who will make memories there. Okay, but what if those sweet old grandparents who handed you the keys at closing haven’t taken care of their home? This is no joke—the National Fire Protection Association actually lists Demographics as one of the Top 5 causes of house fires.

If that sounds like a loaded term, well, it is. A Victorian home owned by a family struggling to make ends meet is far more likely to have deferred maintenance issues than an identical Victorian owned by a wealthy commuter. The same holds true for elderly homeowners, or people who have lived in the same home for more than a generation. They tend to put things off or become “nose-blind” to chronic problems that could have fire-safety implications. The NFPA isn’t judging—they’ve just picked a word and slapped it on a statistic.

What You Can’t See Can Hurt You

www.istockphoto.com

Something else you might ask the seller of an older home is whether it was built with balloon framing, which was a popular money-saving decision for builders from the 1860s to the 1930s. “Balloon frame construction is a wood framing method where exterior wall studs are continuous from the sill plate to the roof plate,” Chief Duelks explains. “Floors are attached to ribbon board, with no fire-stopping structure within the walls.”

Instead of sitting on heavy timbers and skillfully crafted connecting joints, floors basically sit on the walls; you’ve probably heard the term “load-bearing” and this is what it means. The outside walls are basically hollow and, in a fire, can act like chimneys, carrying a basement fire to the roof in a matter of minutes.

“Fires can be concealed and travel thru the void channels unnoticed in balloon frame construction,” Duelks adds. “When smoke is visible from the attic, a team should be sent to ensure there is not an active fire in the basement. A fire in the basement can travel all the way to the attic unnoticed thru the void channels.”

Since the 1930s, platform framing has addressed this issue. If you are planning to make an offer on a home with balloon framing, make sure to figure in the cost of blowing foam insulation into the exterior walls, which has the added advantage of preventing the “chimney effect.”

Speaking of chimneys, in older homes a regularly used fireplace can create potentially combustible creosote deposits over time. When they ignite, the resulting chimney fire can be extremely destructive. Also, older flue linings can crack, which can increase the possibility of a fire. A pre-sale chimney inspection has become a common ask from buyers. If you didn’t get one, get one.

In Westfield, where many structures date back to the mid-1800s, Chief Duelks says that it is not unheard of for homes to have secret rooms, tunnels, and passageways that lead to other buildings—adding to the many challenges firefighters encounter when responding to calls at what he terms “historical-built” houses.

Un-Handy Men

An overlooked fire issue in older homes is the renovation work that is sometimes undertaken in the months after purchase. Often, buyers will want to address deferred maintenance or make upgrades before they move in. Historic homes and open flames are not a good combination, which means you’ll want plumbers, roofers and other contractors working with heating elements to have experience in old houses. For example, some roof repairs (flashing for instance) may involve a torch. Is there a layer of tar paper hiding beneath? Torch-down roofing on a flat roof section? It is as dangerous as it sounds in inexperienced hands. What about the plumber who sweats a joint and then packs up for the day? During cold-weather renovations, workers often bring powerful space heaters into old homes. Do they know whether your electrical system can handle those heaters?

If a big renovation is in your plan, in addition to picking a contractor with a track record in similar homes, make sure that the materials the contractor plans to use are the same quality as the rest of the house. “Modern” isn’t always better, even if it saves you a couple of bucks. A wood floor may cost more than vinyl flooring but, in a house fire, a wood floor may give you the few extra minutes that save your family’s life.

Chief Duelks points out that the same fire-safety rules that apply to new owners of historic homes apply to owner of all homes (and vice versa).

“All homes, regardless of the age, should have smoke and carbon monoxide detectors,” he says. “A fire extinguisher should also be within visual site of the kitchen in the event of a kitchen fire. Hire a reputable company to perform a home inspection as well as licensed contractors. Operating smoke and carbon monoxide detectors are extremely important, they save lives. Never hesitate to call the fire department if the alarms activate or if you may have concerns. Finally, have a plan to get out fast, designate a meeting place outside your home for all your family members and practice your safety plan at least once every six months.”

As mentioned earlier, buying a wonderful old home does not increase your chances of experiencing a catastrophic fire. What it does is up the ante on following basic fire-safety and fire-prevention rules everyone should be following anyway.

More from the NFPA

www.istockphoto.com

A recent report by the National Fire Protection Agency looked at a period (2015 to 2019) prior to the pandemic and came up with the following numbers:

- 26% of all reported fires in the US were home structure fires

- US fire departments responded to an average of 346,800 home structure fires a year

- 69% of home structure fires occurred in one- or two-family homes, but accounted for 85% of fire deaths

- The number of home fires and home fire deaths is half what it was in 1980; most of that reduction came between 1980 and 2000

Editor’s Note: Mark Stewart has owned two homes built in the early 1900s, another in the mid-1800s, and recently purchased a property built in 1795. So far, no fires. Special thanks to the Westfield Fire Department and Elizabeth Fire Department for their help with this feature.

It’s never just the destination. It’s always the journey.

As a child growing up in León, Mexico, I often imagined what life in the United States might be like—riding yellow school buses and eating peanut butter sandwiches for lunch, just like they did in the movies. My parents were college graduates. My mother had a degree in textile design and my father owned a company that made machinery for the leather manufacturing industry. We had never struggled, never had to move.

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

A recession in Mexico in the early 2000s changed all of that. I sensed my parents were dealing with money troubles even though no one mentioned it. One day, debt collectors came and removed beautiful pieces of furniture from our home. I remember my nanny yelling at them to get a job that didn’t ruin people’s lives.

Soon after, we boarded a flight to the Pacific Northwest, where a family friend had put down roots five years earlier. And we began a new life. My mother worked as a house cleaner and my father labored in construction to support our family while they negotiated a path through an immigration process that was so long and so complicated that their visas expired, leaving them in legal limbo. When people asked about my legal status, I would lie and say I had a green card. At school, kids Fast-forward to 2018, three months after my twenty-fourth birthday, I found myself single, divorced, and living alone. That summer, I was sicker than I’d ever been, fighting illness after illness and stomach aches from constant stress. My body and self had diverged. I no longer wanted to feel disconnected, so I started cooking at home. The food I made offered a new identity, creating a path that led me back to myself as a Mexican immigrant. With no one to tell me what I could and couldn’t cook, I started to make the dishes that I missed from my childhood. It was a chance to rediscover my heritage and an opportunity to heal. Cooking these dishes was an act of self-love for the part of myself whose country said I was never enough and could never fit in.

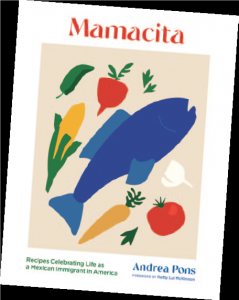

The recipes in this story remind me of home. My childhood home and, now, my new home. They are among the many that I collected and published in a book entitled Mamacita: Recipes Celebrating Life as a Mexican Immigrant in America. From looking through the culinary articles and restaurant reviews in EDGE, I know that readers of this magazine have sophisticated and adventurous palates. They crave “authentic.” I believe an important component of authenticity in any cuisine that comes to America from another place is an appreciation of the journey of the people who bring it here.

In 2018, when I started the Mamacita project, I had an expired green card. I received an official letter from the government stating I had two years to apply for citizenship or an extension. My path to citizenship was both unique and common. The immigration system is a labyrinth, and while many of us find ourselves in the same maze, finding our way out is a personal puzzle that we are often left to figure out on our own.

Applying for citizenship as a Mexican immigrant requires a level of privilege greater than most have access to or can afford. I didn’t make enough money, and my family didn’t either. I had to ask a family friend, Vicente, who then worked for Boeing, to be my sponsor—which was not a small request. Essentially, he signed a contract stating that he would be financially responsible for me if I lost my job or declared bankruptcy. If Vicente had been unable to aid me financially, then the government could have sued him. Thanks to Vicente, I was able to start the application process and become a U.S. citizen. He has since passed, but I will never forget his kindness and the generosity he extended to our family.

People who believe immigration is quick and uncomplicated haven’t gone through the system. It’s intimidating and confusing for everyone, especially those who have to go through it. It’s almost impossible to start without being financially stable. Often, people assume we aren’t paying taxes. Even if we don’t have status, we still pay taxes. The process of obtaining status can take a very long time—ultimately, it took me 15 years. Immigration laws frequently change, adding higher costs and increased complexity.

Indeed, in June 2020, I was confronted by the reality of deportation, and I’ve never been more scared. In a panic, I called my immigration lawyer—a privilege not everyone has— and discovered I had to start the application process all over again. Ten years of previous immigration paperwork no longer applied to my case! When that happens, you have no choice but to start over. For the record, there are no refunds for the applications that no longer apply. Ten thousand dollars later, I found myself on a new path toward the same goal.

Uprooting my life taught me that the only thing we can expect is everything we didn’t plan to happen. Months after the initial call to my lawyer, I sat at the office of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), waiting to see whether I had passed the test. After spending two hours answering a series of life-altering questions, I did it. I achieved my parents’ dream, my dream—the American dream. With a certificate in one hand and a dollar-store American flag gripped in the other, I could finally call myself a citizen of the United States.

I know it sounds dramatic, but cooking saved my life. Making these dishes helped me crawl out of a dark place of hiding and provided a space where I could finally show up as my whole self. By immortalizing the recipes that I grew up eating as a kid in Mexico, I reconnected with the part of myself I never meant to forget. My mother, like my grandmother, has yet to use a measuring spoon. Instead, she is guided by the palms of her hands, knowing by heart how much to add. I have written these recipes down, added measurements, and simplified the process so you can make my family’s recipes on your own or invite the people you love to share a meal together.

There is no greater pleasure than serving food to the people you love and seeing the delight on their faces when they taste something made just for them. When you make these recipes, I hope you feel more connected to the immigrant communities around you. I want us to keep striving to show up, help other immigrants to speak up, and listen to each other’s stories. Most of all, I hope my story reminds you to trust yourself. Wherever you are now, who you are meant to be is entirely up to you.

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

Salsa Verde

Green Salsa | Makes about 3 cups

Growing up, we had various types of salsas in the fridge at all times. But there were two that never ran out: salsa verde and salsa roja. My mama would make a fresh batch every weekend for the week ahead. This salsa verde is incredibly versatile and can be used in many dishes; my favorite ones are chilaquiles verdes and pozole verde. You can additionally top a quesadilla with this salsa, mix it into your guacamole for a spicy dip, or simply eat it with tortilla chips. The options are limitless.

9 ounces tomatillos (about 6), divided

1 tablespoon avocado oil

1/2 cup chopped white onion

2 fresh jalapeno peppers, seeded

1 canned jalapeno pepper

1 tablespoon fresh lime juice

1/2 cup chopped cilantro leaves

1 teaspoon sea salt

Peel off the tomatillos’ paper husks and rinse under cold running water. In a large saucepan, combine half of the tomatillos and enough water to cover them and bring to a boil over high heat. Reduce the heat to medium-high and cook for 3 minutes to soften the tomatillos. Remove the tomatillos with a slotted spoon and reserve ¼ cup of the cooking liquid. Meanwhile, heat the oil over high heat. Sear the remaining tomatillos, flipping once, until brown, 1 to 2 minutes on each side. Remove from the heat. In a blender, add all of the tomatillos and the reserved ¼ cup of liquid. Blend until smooth. To the blender, add the chopped white onion, all of the jalapenos, the lime juice, cilantro, and salt. Blend until combined. Be careful not to liquify the salsa; it should be smooth with some texture. Taste and adjust the salt or lime juice as needed. Transfer the salsa to a sealed container and refrigerate.

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

Carne en Salsa Verde

con Papas

Pork in Green Sauce with Potatoes | Serves 4 to 6

El Dia del Padre in my household is always celebrated with a big plate of this Carne en Salsa Verde con Papas. My dad rarely likes to enchilarse (purposely eat spicy food to feel a burn), so he has always loved when my mama cooks dishes like this, which have all the flavor but very mild spiciness. I grew up to really love this dish, specially rolled up in a tortilla with a little bit of crema to make the salsa creamier. The green color comes from the tomatillos, but unlike their name suggests, tomatillos are not “little tomatoes,” or tomatoes at all, for that matter. Think of them rather as a cousin of the tomato. While tomatillos can turn yellow, red, or even purple with full maturity, they are only eaten unripe in Mexican dishes. When shopping for tomatillos look for ones that have dry and papery husks, avoiding those that feel moist, look shriveled, or feel damp. If buying tomatillos ahead of time, store them in a cool dry place and never place them inside the fridge.

1 pound boneless pork loin, cut into 1-inch cubes

Sea salt and ground black pepper

1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

1 tablespoon olive oil

2 cups husked, rinsed, and halved tomatillos

¼ medium white onion

1 garlic clove, minced

2 jalapeno peppers, seeded

2 tablespoons chicken bouillon powder

2 cups halved baby potatoes

Cooked rice for serving

Warm tortillas for serving

Season the pork loin with salt, pepper, and garlic powder. In a deep, medium skillet, heat the oil over medium heat. Sear the pork, flipping, until browned, 2 to 3 minutes on each side. Do not cook the pork all the way through. Remove the pork from the pan and set aside. In a blender, combine the tomatillos, onion, garlic, jalapenos, chicken bouillon powder, and 4 cups of cold water. Blend well. In the same skillet, add the sauce, bring to a simmer over medium heat for 2 minutes. Add the pork and baby potatoes and bring to a boil over medium-high heat. Reduce the heat to low, cover, and simmer until the potatoes are soft, about 30 minutes. Serve with a side of rice and warm tortillas.

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

Crema de Elote

Cream of Corn Soup | Serves 4 to 6

This creamy corn soup comes together in less than an hour, and it’s sure to be a crowd pleaser. If dairy is not your thing, I recommend using ghee for butter and cashew milk as an alternative. While most milk alternatives will work, cashew has the closest consistency and taste to dairy milk. If choosing alternative milk, stay away from coconut milk as the taste of coconut will be too strong for the soup and will overpower the true star of the dish, corn.

6 cups whole milk, divided

2 large ears corn, shucked

2 teaspoons chicken bouillon powder

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

Sea salt

2 poblano peppers, roasted, peeled, seeded, and sliced into “rajas” (strips)

Queso panela, cubed

In a large soup pot, bring 5 cups of the milk to a simmer over medium-low heat. Continue simmering for 5 minutes. Using a sharp knife, cut the corn kernels off the cobs. In a blender, combine half of the corn kernels and the remaining 1 cup of milk and blend until smooth. Using a strainer, strain the corn mixture into the soup pot. Mix well. Add the remaining corn kernels, the chicken bouillon powder, and the butter. Simmer over medium-low heat for about 10 minutes. Do not overcook as the corn will make the soup too sweet. Season with salt. Serve hot, topped with the rajas and queso panela.

Albondigas en Chipotle

Meatballs in Chipotle Sauce | Serves 4 to 6

In Mexico, work hours are different than in the United States. Instead of working nine-to-five with a 30-minute or hour lunch break, Mexico—a country that revolves around the next meal—has a scheduled block of two hours around three o’clock in the afternoon when people go home for comida (a midday meal that is spent with family, and the equivalent of dinner), then head back to work for another few hours before returning home around eight o’clock in the evening. This was my papa’s schedule when I was a kid. On special nights, he would return home to surprise my sister and me with a rented VHS tape. I remember the night he brought home Lady and the Tramp. Not only did my sister Vanessa and I both love this movie, but it was also the first time we ever saw meatballs served with spaghetti instead of rice. Traditionally albondigas are served in soup, but my mama preferred to serve them dry over rice or potatoes, topped with salsa. Eating albondigas takes me back to a simpler time, sitting on the floor with Vanessa, watching two dogs kiss over a plate of meatballs and stringy noodles.

For the Meatballs…

¼ cup all-purpose flour, plus more as needed

1/2 pound ground beef

1/2 pound ground pork

2 tablespoons finely chopped onion

1 garlic clove, minced

2 teaspoons finely chopped parsley leaves

2 teaspoons panko bread crumbs

1/2 teaspoon sea salt

¼ teaspoon ground black pepper

2 large eggs

¼ cup plus 2 tablespoons avocado oil

For the Salsa…

5 dried chipotle peppers, seeded

3 large tomatoes, halved

2 tablespoons finely chopped white onion

1 garlic clove, minced

1 tablespoon tomato puree

2 tablespoons avocado oil

Sea salt

Cooked rice for serving (optional)

Mashed potatoes for serving (optional)

Making the Meatballs…

Place the flour in a shallow bowl. In a large bowl, combine the remaining meatball ingredients, except the oil and mix, with your hands. Make chestnut-sized one-inch balls out of the meat mixture. Roll the meatballs in the flour and set aside. In a deep skillet, heat the 6 tablespoons of oil over medium-high heat. Briefly sear the meatballs until they turn golden brown. Set aside. Making the Salsa…

In a dry skillet over medium heat, lightly roast the chipotle peppers. Transfer to a soup pot, add 2 cups of water, and bring to a boil. Cook the peppers until they soften, 5 to 7 minutes. Drain the peppers, reserving 1 cup of the cooking liquid. Set aside. In a blender, combine the softened peppers, the reserved 1 cup of cooking liquid, the tomatoes, onion, garlic, and tomato puree. Blend until smooth. In a stockpot, heat the 2 tablespoons of oil over medium heat. Add the blended sauce and fry for 3 to 5 minutes. Add the meatballs and 1 1/2 cups of cold water. Bring to a boil for 1 minute, then cover with a lid and simmer over medium-low heat for 15 minutes. Season with salt. Serve with rice or mashed potatoes.

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

Cebiche

Serves 4 to 6

Ceviche or cebiche? The spelling depends on the zone of Mexico in which you are eating this dish. Because I grew up knowing it as cebiche, I decided to keep this spelling instead of ceviche, which is more commonly known in the United States. Like the variation in spelling, this dish has many modifications of ingredients depending on the region and who is making it. A lot of my mama’s recipes have a strong Spanish influence, which you can see in the addition of olives to many of her recipes, including this one. I like cutting my fish into cubes instead of strips. The cubes must be bite-sized—not too small and not too big—as traditionally, cebiche is served in a bowl and scooped up with tortilla chips to eat.

1/2 pound fresh halibut fillet (or swordfish)

1 lime, juiced

1 teaspoon sea salt

4 medium tomatoes

1/2 medium white onion, chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

1 bunch cilantro leaves, chopped

10 green olives, pitted and halved

2 large jalapeno peppers, seeded and coarsely chopped

1 medium Hass avocado, cubed

¼ cup olive oil

2 teaspoons white wine vinegar

All photos courtesy of Andrea Pons and Princeton Architectural Press

Rinse the halibut under cold running water and pat dry. Chop into 1/2-inch cubes. In a salad bowl, bathe the halibut in the lime juice, tossing so it doesn’t “cook” unevenly. Season with salt and cover the bowl with plastic wrap. Place the bowl in the fridge for 1 hour. In a medium saucepan, combine the tomatoes and enough water to cover them. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat and cook until the skins begin to split, about 1 minute. Drain and rinse the tomatoes under cold running water. Remove the skins with a paper towel. Chop the tomatoes into small cubes and set aside. Remove the halibut from the fridge, add the tomatoes, then add the onion, garlic, cilantro, olives, peppers, avocado, olive oil, and vinegar. Mix gently. Taste and season with salt as needed. Serve with crackers or tortilla chips.

Editor’s Note:

Andrea Pons is a senior production manager, food stylist, and author based in Seattle, Washington. A new, expanded edition of Mamacita: Recipes Celebrating Life as a Mexican Immigrant in America (Princeton Architectural Press • $29.95 at papress.com) was released in 2022.

A Most Maligned Generation Makes its Case

www.imdb.com

EDGE asked me to defend millennials. They didn’t say from whom, but our detractors are many and apparent enough that a shotgun approach makes sense. I’ll start with Gen X, who think they’ve flown under the Boomer monolith well-disguised. Millennials, in their opinion, are narcs who rise from bed each morning to champ at carrots on strings. Digital carrots mainly. We are Yuppie 2. We are Patrick Bateman, Brett Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, whose struggles with cognitive dissonance in the white-collar workspace led to a barely discriminate murderous rage. In the dead eyes of millennials, the same sickly id that burned through Bateman’s moisturizing face mask.

We missed the point. Patrick Bateman is “literally me,” we say. And while investment banking as an industry has fallen in prestige and relevance, perhaps because the Boomers got too excited and overdid it with everyone’s money, we unironically align ourselves with the values of that zombie industry: a cut-throat imperative to optimize at the expense of peace, health, and comfort.

Millennials are, on the whole, more like bad guys from Gen X media. We are not the soulful slackers embodied most totally by Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke in those Linklater movies about having sex with someone from the bus. We could never be. Millennials haven’t the patience to sustain that kind of drifting conversation (it’s been done to death) and we don’t make eye contact on public transit. We don’t slack because Gen X already overdid that. Gen X moved through slacking like a hatch of locust, consuming all idle time in anticipation of the millennium, when things were expected to pop off, either via the second coming or a computer glitch that was going to ruin the way we calculate time.

In retrospect, Jesus II or Y2K would’ve been better than what we got. Not to be a wet blanket (some would say self-pity is inextricable from the basic millennial makeup) but most millennial children grew up in the shadow of domestic paranoia instigated by 9/11. Somehow, maybe illogically, most children in my elementary school were afraid of being abducted and beaten with a shovel on our morning bike rides to school (we pedaled very quickly) perhaps because our Gen X and Boomer parents instilled the idea, perhaps because they thought hairline cracks of ill will radiated out from that singular evil. Also Columbine and its tenuous connection to video games. We grew up in a weaker Western world with an oozing wound no one wanted to look at too closely.

www.imdb.com

We were made to think, on the heels of these travesties, that threats to our lives were omnipresent, both within and without the domicile. This has more or less proven true, a seeming result of the social contract’s disintegration, more loneliness, an increase in parasocial relationships with video game streamers, and the total invasion of the internet, that recirculator of incomplete ideas. In a failed effort to prevent this reality, participation trophies were created for children’s soccer. In revenge for their own stupid idea, the Boomers bullied us, five-years-old at the time, for receiving them. Were we supposed to decline them like Marlon Brando at the Oscars? We didn’t know about causes yet. We might’ve said something about the climate.

Climate discourse is irritating, even for those who believe in and understand it. Its self-congratulatory and fatalistic tone makes engagement difficult. Climate zealots, like most people, are strapped to the planet earth. Their constant ponderance of its destruction is creepy, like most morbid fixations. I’d generalize that most millennials would enjoy the luxury of burning all of their garbage on the front lawn. It seems like something we’d be into. But there was always an understanding, perhaps more pronounced in households with composting pots, that millennials could be the last generation to reach old age on an intact Earth. And by old age we mean sixty, maybe. These same climate types view Gen Z, the Zoomers, most of whom were born after the millennium, with the same pity farmers reserve for sheep who come out with three eyeballs and no skin. Misbegotten in a land after time, the Zoomer rides this burning world to its final destination—and also thinks millennials are losers.

www.imdb.com

www.imdb.com

I asked my students about my generation. I am an English instructor (adjunct) who teaches sixty Gen Z students, some of whom show up to class, and many of whom don’t wear airpods while I’m talking. They’re personable. I don’t get the impression many of them are driven to accomplish anything, but I do teach an 8:00 a.m. class. In response to a brief, informal survey, my students concluded that the worst thing about millennials is their solipsism, followed next by our precocity, which has aged very badly. How can so many of us be precocious? The numbers don’t add up. They’re fascinated by the fact that any of us can marry, let alone reproduce. (We do so later and less often.) Also we are cringe, they say, and cite AOC. But she is a politician. She is supposed to be cringe.

As with all generational archetypes, the insidious puppeteer at play is advertising. Millennials were the first group to be sold on total self-sufficiency with banner ads about cocktail sets, chefs’ knives, paracord, titanium camping stoves, kettlebells, and the Peloton. The cohesive idea, if there is one, is that millennials could purchase enough clutter to replace bars, gymnasiums, and even the outdoors of planet Earth, with all its winding bike trails.

www.imdb.com

www.imdb.com

These products and their market strength preceded the pandemic. Their strategic sense is predicated on social anxiety and the prohibitive cost of leaving one’s apartment. The self-reliance these devices promise to enable is obviously a fantasy. Millennials are as ingrained as any other Americans into the tapestry of this country. We think, directionally, in terms of the streets and landmarks that Boomers built. Stylistically, we’ve reverted to the oversized, bodily disguise of Gen X. Musically and entertainment-wise, we’ve been stratify, delineate, and say precisely what things were so that we might retire, satisfied with our explications, to an overpriced two bed with pillows that say “pillow” on them. outpaced by curly, dangly, hive-minded Gen Z, who have unified their image more rapidly and comprehensively than millennials. The legacy of millennial culture—through music, movies, academics and fiction—will be of ceaseless infighting and gatekeeping, a desire to

www.imdb.com

I’m not upset, exactly, with how millennials are portrayed and understood. I’m only woozy from the dissonance. Greta Gerwig is cusp, born in ‘83, and Diablo Cody, who wrote Juno, and who was born in ‘78, is squarely Gen X. The guy who wrote Scott Pilgrim is also Gen X, ‘79. Our stories were conveyed to us, and with an unprecedented degree of gullibility and receptivity, we incorporated them directly into our image and ethic. We deserve scorn for that, derision. Also, we turned country music into guys who wear high-vis vests and flat brims. We financially enabled Logic, the corniest rapper of all time, to develop a positive self-esteem. Neil Young was on when some of our Canadian parents reproduced, ergo Arcade Fire, a band with an unprecedented reach into its own colon. For these reasons and others, we hate ourselves and do not resemble ourselves, at least anecdotally. None of my friends like this stuff, maybe excepting Arcade Fire, who toggled something chemical in us when we were the right age.

My theory is that Gen X cooked up some millennials in a petri dish to satisfy their own vision for the future human, a sort of ubermensch of prevarication and ennui. By a similar token, we’ve created the e-girls and e-boys of Instagram through collective will and approval, probably to satisfy a more embarrassing desire. In other words, the most visible flagbearers of a generation satisfy the tastes of the monied, landed, enfranchised cohort preceding them. For a long time, this was only the Boomers, and for a long time every station was classic rock, but the emergence of a more cohesive Gen X in the media, and the absorption of the elder millennial cohort by this same bolder Gen X, is probably to blame for the millennial image. That stuff, the participation trophies, and the ice caps.

www.imdb.com

It’s not a defense, is it? It’s disavowal with some redirection mixed in. Some of my points have the tone of conspiracy. But the media machine is intentional, insidious, and directed. It generated the typical millennial, who is either Michael Cera or Emma Stone, both ‘88. We have to ask why, I guess. Who wanted them? Their parents? Their parents. Their children will want them. Their friends and so on. We’ll never have the consensus approval of the Boomers, who awarded it to themselves. And until there’s another world war and another housing boom…

Both of these things are possible. China is poised to invade Taiwan and the older Boomers, presently 77, are less than a year away from the national life expectancy. It could all line up in a bath of nuclear fire and heart disease, and our children (given the older-adjusted age of marriage and reproduction in America) might end up in possession of America’s next monoculture. Our children—who will have at this point developed radiation-resistant fur in an unprecedented Lamarckian response to Earth’s inhabitability problem, will look to us for some answers. And some of us will inevitably play Frances Ha, eternally black and white, dooming the rest of us for however long we have left.

My hands-on nursing adventure in Dar es Salaam.

Three planes. Thirty hours. Tired, nervous and excited, I collected my bags on a Saturday at Julius Nyerere Airport in Tanzania and prepared myself for my first day as an intern in the labor ward at Muhimbili University National Hospital in Dar es Salaam. I was one of 40 or so volunteer medical and nursing students sharing a house owned by Work the World, a program specializing in healthcare internships in Africa and Asia. My goal was to gain hands-on experience and clinical hours in obstetrics between semesters at the Trinitas School of Nursing. I was starting on Monday.

I think of myself as an adventurous person and I have done more traveling than most—to Southeast Asia twice, several countries in Europe, and Mexico several times. I am comfortable interacting with people and respectful of their cultures. I had never been to Africa, however, and was not familiar with Tanzania before I arrived. I was unsure what to expect, although I knew that the hospital where I would be working was not going to be comparable to anything we have here in the United States.

I think of myself as an adventurous person and I have done more traveling than most—to Southeast Asia twice, several countries in Europe, and Mexico several times. I am comfortable interacting with people and respectful of their cultures. I had never been to Africa, however, and was not familiar with Tanzania before I arrived. I was unsure what to expect, although I knew that the hospital where I would be working was not going to be comparable to anything we have here in the United States.

I am somewhat of a latecomer to nursing. I had been interested in the profession when I was 18, but it seemed really hard to me at the time and I questioned whether I could handle it. I went to college and earned a communications degree and then worked in the franchising industry for nine years.

When I was 29, my father was admitted to the hospital for an emergency triple-bypass. I worked remotely for several days from his hospital room and, while I was there, I talked with the nurses a lot. The whole experience with my dad (he pulled through and is doing fine) reignited my interest in pursuing nursing as a career. I started classes at Trinitas in January of 2020—great timing, yes, I know—and graduated in January of 2023.

I am the oldest sister in my family by 10 years and the oldest cousin by eight years, so I basically remember when everybody in my family was born. I found this more exciting than anything else in my life as a young girl. So as I started nursing school, I was interested in obstetrics and knew I wanted to go into labor and delivery. I conveyed this to my professors, who advised me to wait a year and keep my options open. But once we were in our semester of obstetrics, I knew that’s where I wanted to be.

Siblings are typically close together in age and don’t remember the experience of being in the hospital when their younger sisters and brothers are born. But I was 10 when I met my little sister, within an hour of her being born. I wasn’t in the delivery room, but I remember being there with my mom and holding her. She was so tiny. It is one of my core memories. I remember what I was wearing and what it smelled like there and the feeling of amazement of seeing this baby that just came into the world—and being amazed by my mom. Since then, I’ve always been interested in the birth experiences that women have.

The first time I was in the delivery room at Trinitas, I really felt like I was part of a team. It all seemed very natural to me. The baby was born after a long, 24-hour labor. It was striking how much work the mother did, how exhausted she was, and how miserable she was while going through the most physically difficult thing she’ll probably do in her life—and then seeing that “switch” when she was holding her baby for the first time and how all that suddenly didn’t matter. She was happy and glowing and crying. And I was crying.

The first time I was in the delivery room at Trinitas, I really felt like I was part of a team. It all seemed very natural to me. The baby was born after a long, 24-hour labor. It was striking how much work the mother did, how exhausted she was, and how miserable she was while going through the most physically difficult thing she’ll probably do in her life—and then seeing that “switch” when she was holding her baby for the first time and how all that suddenly didn’t matter. She was happy and glowing and crying. And I was crying.

I have been in the room for a lot of births and delivered several babies myself since then…and I still cry every time.

I came across Work the World while searching for a summer labor and delivery internship. In Europe, where the program is based, midwifery is kind of parallel to nursing. In the UK, for instance, nursing students do not typically learn about women’s health. To gain that knowledge, they often volunteer for midwifery programs abroad. Here in the US, the nursing programs are more comprehensive and include obstetrics training, but students are only allowed to watch procedures, not get their “hands dirty.” Often, your first chance to put a learned skill to work may not come until your first job.

Sure enough, I received valuable clinical training working directly with patients and midwives, assisting in deliveries on a daily basis. I was able to do things that nursing students here just don’t get to do. For instance, we had to take a phlebotomy course, I learned how to start IVs there, I administered oxytocin to induce labor, and I learned how to handle all types of monitoring. I delivered four babies and scrubbed in on five c-sections. One of my deliveries was breech and another involved shoulder dystocia. Each mother of these four babies I had supported throughout her labor, from two to 10 hours. There were other mothers for whom I was there during all stages of labor. After delivery, I was constantly assessing the mothers and the babies. They were my patients.

The midwives ran the show in the labor ward at Muhimbili Hospital. Most were very caring and nice toward the mothers, but there were a couple who regarded their patients as being uncooperative when they were just in a lot of pain. There are no epidurals and no pain medications available for mothers there and when they yelled the midwives would sometimes yell back. Some practices I witnessed would be unheard of and unacceptable in the US, and I found them very upsetting at times. But I wasn’t there to criticize how they treated their patients. I was there to learn.

Along with the learning opportunity came certain challenges for which it turned out I was unprepared. Resources we take for granted here are scarce to non-existent. For example, we had one fetal heartrate monitor for the whole floor, no IV pumps, and there were no individual rooms for the patients. Each area was divided into bays by plastic curtains. In each bay was a bed, a stool and an empty nightstand. Patients brought their own supplies to the hospitals—including sheets, pillows and drinking water. The only thing provided was a basic Foley catheter. The different wards in the hospital were connected by outdoor walkways. There were few if any doors separating inside from outside, including in the surgical ward.

Along with the learning opportunity came certain challenges for which it turned out I was unprepared. Resources we take for granted here are scarce to non-existent. For example, we had one fetal heartrate monitor for the whole floor, no IV pumps, and there were no individual rooms for the patients. Each area was divided into bays by plastic curtains. In each bay was a bed, a stool and an empty nightstand. Patients brought their own supplies to the hospitals—including sheets, pillows and drinking water. The only thing provided was a basic Foley catheter. The different wards in the hospital were connected by outdoor walkways. There were few if any doors separating inside from outside, including in the surgical ward.

Another surprise was that I was the only American in the program. Most of the people living in the residence were from the UK or Europe. There were a couple of people from Australia and a couple from Turkey. There was a lot of change over. Every week new people were coming in. There were eight of us that came in my week. We stuck together and became pretty close, and we’ve all kept in touch.

Every morning we would travel to the hospital in little three-wheeled taxis called tuk tuks. The culture in Dar es Salaam (the translation of which, by the way, is Abode of Peace) caught me off-guard a couple of times, especially the way women are regarded. Where the hospital was located in the city wasn’t a very touristy area and—as a group of independent, educated women without a man present—we were not always treated respectfully by the local people. It was the first time in all my travels that I felt that uncomfortable.

In the hospital, however, I was completely in my element. When there were issues that needed to be addressed quickly, I proved to myself time and again that the training I was receiving at Trinitas would kick in when it was needed. I could step up and do what I had to do in the moment when there was no time to think about it. When we had a post-partum hemorrhage, for instance, I knew exactly what I had to do to start IV lines and get fluids into the patient in order to get her into surgery. I jumped right in and did it like it was second nature.

In Tanzania, I gained tremendous confidence being put in situations that I had only learned about in a lecture. During my time at Muhimbili University National Hospital, I was able to apply absolutely everything I learned at the Trinitas School of Nursing to my patients in Tanzania—and I know that everything I learned in Dar es Salaam I will bring into my future nursing practice.

In Tanzania, I gained tremendous confidence being put in situations that I had only learned about in a lecture. During my time at Muhimbili University National Hospital, I was able to apply absolutely everything I learned at the Trinitas School of Nursing to my patients in Tanzania—and I know that everything I learned in Dar es Salaam I will bring into my future nursing practice.

In nursing school, you get so much information that occasionally you wonder whether, when the task is in front of you and you need to help somebody else, Will I be able to do it?

When you get that chance and your instincts kick in and you do the right thing, afterwards it’s a really good feeling.

Editor’s Note: Alexandra Redmond will be taking her boards early this year and hopes to be working in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in 2023.

Editor’s Note: Alexandra Redmond will be taking her boards early this year and hopes to be working in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in 2023.

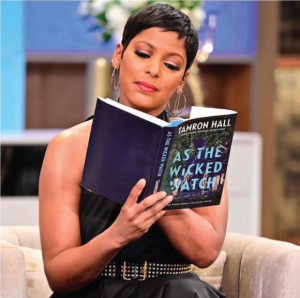

EDGE Interview

There is no magic formula for breaking down barriers. The individuals who do so, by nature and definition, are the ones who bring unique skills and perspective to an obstacle where others have tried and failed. Tamron Hall began her career in broadcast journalism as a small-town reporter and outworked, outhustled and, let’s face it, “out-Tamron’d” the competition until she was co-hosting the third hour of Today, sitting behind the anchor desk on NBC Nightly News and had her own primetime hour on MSNBC. In 2019, she launched The Tamron Hall Show, a syndicated talk show that has already won her a pair of Daytime Emmys. Gerry Strauss was curious how a gifted storyteller with a passion for detail could make such a splash in a format where other people do the talking. It turns out, Tamron Hall’s other secret power is listening.

EDGE: Have you always been intrigued by people and their stories?

TH: I have. My grandfather, who was born in 1901, lived on a very small street in Luling, Texas called Cosi. All of the people there had either been sharecroppers or had worked in conditions that were the real challenges of black Americans. And that’s putting it lightly. I was always curious about their lives. There was a woman named Mama Susie, who was a hundred years old. I think I was 10. I would go down and talk with her. She was a midwife who had outlived all of her children and her husband. So I guess, looking back, I was always honing the skillsets needed for my job. I just didn’t know it.

EDGE: When did the idea of becoming a television journalist start?

TH: When I was a teenager in the ’80s. I finally saw a woman doing it that looked like me. My father and I were watching television one day—I was not being the best student, we’ll say—and he said, “If you get your grades up, that could be you.” He pointed at this woman, Lola Johnson. At the time, she was the first black woman to anchor the news in North Texas. I saw a black female journalist, I saw this anchorwoman who was sitting next to this white man, and she was as composed and as strong, and had this really beautiful, rich, baritone voice. Wow! There was something about it emotionally that connected in a way that nothing had prior to that. I grew up like any kid at that time, with Michael Jackson and Madonna posters on my wall. I ran out to the mall to get all the bangles and the layers that Madonna wore in her “Borderline” video. I was an MTV junkie. I loved that…but I knew I couldn’t do that. Seeing Lola Johnson, there was something about her delivery of the news that I felt was my destiny. This was a job I hadn’t known was possible. It was not on the list of things when you have Career Day at Carroll Peak Elementary School in Fort Worth, Texas.

Heidi Gutman/Disney General Entertainment

EDGE: As a black woman in your field, was it an uphill battle to earn the types of serious, high-level assignments that would help enhance your reputation as a journalist?

TH: Oh, I think it’s still challenging for me, to be quite honest. The first and only time I’ve ever lost a job in my life, I was 48 years old and I’d been a journalist for 30 years. I went into interview for job opportunities after leaving the Today Show as the first black woman to ever do that show. I’d won an Edward R. Murrow Award and had been Emmy-nominated for work that I’d done as a consumer reporter and covering the election of Barack Obama with the NBC News team. I’d filled in that last week for Lester Holt. I hosted my hour of the Today Show. I filled in for my friend Savannah Guthrie, who was on maternity leave, and hosted my hour on MSNBC. I went into a number of news organizations who essentially were offering me kind of journeymen fill-in roles. I remember a conversation where someone said, “Oh, well, someone’s going on maternity leave.” I said, “Oh, Anderson Cooper’s going on maternity leave? I didn’t even know that he was going to have a baby! Congratulations to him.” [Laughs] I say this very cautiously because every opportunity is an opportunity to shine. Some of my biggest breaks were when I got a chance to fill in for someone. That said, direct to your question, I felt my résumé—and the response from viewers when it was revealed that I was leaving—gave me some value. But it didn’t. And I think that is an example of the ongoing challenges, to the question you asked, being a black woman in this industry.

EDGE: Having lived and worked all over the country, in so many different cities, do you feel the perspective you’ve gained makes you a more astute journalist and observer of the world?

Disney General Entertainment

TH: Oh, absolutely. Listen, my summers were spent in Luling, Texas after my mom—who was a 19-year-old single mom—took advantage of an opportunity in a bigger city so she could become the person that she wanted to be, a teacher. This was a very small, rural town. Even now, when my relatives are ill, they’ve got to drive 45 minutes or an hour to just see a doctor—and I’m not talking about specialists. There is one doctor who comes in to Luling who provides medical care—I believe it’s like once or twice a week—to people who cannot afford to go into Austin or Houston. That happens right now. I have a relative who was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. For her to see anyone, she’s got to drive an hour, and she is on government healthcare. I think about that every day I walk through the streets of New York and I see a rental that’s $30,000 a month for two bedrooms. This dichotomy not only has helped my journey as a reporter, it helps my journey as a human. It reminds me I was lucky enough to be a reporter covering some of the biggest stories in a local market, because that gave me perspective on a national scale. I always tell people when someone says to me, “Oh, I hate watching local news,” that you have the wrong perspective, because local news is going to tell you when that highway is closed down that you take every day, or when there is a disaster coming your way in your town. So I was fortunate not only to your point of having lived in all these different cities, I was a local reporter in the streets of those cities.

EDGE: Does this depth of experience make you a better talk show host?

TH: It definitely helped me and what I do right now as a talk show host. I think that when I launched this show, people wondered what it would be. And I always knew that it was going to be those steps that you just mentioned as a reporter, as a kid from a small town, as a kid who’s lived in the heart of Manhattan, and in the smallest street in Luling, Texas. Those tools and those experiences were what I always planned to bring to the show, and that’s why the show is the type of show that it is.

EDGE: When you signed the contract to co-anchor the third hour of the Today Show in 2014—which was a history-making opportunity for you—you chose to wear a jacket that was previously owned and worn by Lena Horne. What was the connection that you felt with Ms. Horne and what she brought to the world?

TH: Growing up, Lena Horne was everywhere. She was this fairy godmother. You know Glinda in the Wizard of Oz? That was Lena Horne for me. I always admired the elegant but strong way she floated through rooms. There was always a presence of power, of strength, of being unapologetic. I also recognized her authentic voice as a kid, in the beauty salon, with my aunt reading Jet magazine, reading Ebony, reading about Lena and Harry Belafonte. I felt that what she represented and embodied was what I wanted out of my career. And so fast-forward when I ultimately lost that job, I thought about how would she have handled it. Would she get down in the dirt and try to leak stories and get mad? Or would she elegantly learn that there are more than one set of wings available? I thought a lot about how she handled adversities that I can’t even imagine—and did it in a way that made black people proud and also made white audiences root for her. That’s something that didn’t happen a lot then when you belonged to the black community. She, in so many ways, belonged to the greatness of America, and the greatness that a black woman can present as a representative of this country.

Disney General Entertainment

EDGE: Having rolled the dice on yourself, and now that The Tamron Hall Show is a such a success, do you feel you were prepared for it?