“The menu divined by Bucco is a coming together of contemporary cooking. He trends seasonal, adds a little local, and comes up with American Med as a core.”

It’s the late 1970s and there’s a small crowd at the bar of the venerable Ryland Inn, tucked back off the whoosh of cars on Route 22 in the Whitehouse Station section of Readington, in suddenly populated eastern Hunterdon County. There are fellows just in from jobs in New York, the  long commute to their new five-bedroom homes on two acres over for the day, there’s a smattering of casual dinner-seekers finishing burgers, there are journalists like me, in between night meetings, stopping in to catch the local gossip in a homey, low-key setting. That Ryland’s a roadhouse, a pitstop on the outskirts of suburbia. By the time it was purchased and re-imagined as a fine-dining destination, with Dennis Foy briefly installed as the name chef—a front man for then-little-known Craig Shelton—Readington and eastern Hunterdon had sprawled confidently into suburbia and many of the denizens in the immediate ‘hood (not to mention surrounding hunt country) were well-heeled and world-wise, ready for haute cuisine in an atmosphere to match, right in their backyards. The 1990s Ryland Inn delivered it all. Soon Shelton was on the cover of Gourmet magazine and the recipient of the food world’s equivalent of an Oscar, a James Beard Award. Ryland catered to the food cognoscente and captains of industry in a seamless operation that defied anything New Jersey had seen. Though its last years were rocky—and the flood that six years ago forced the inn to close was tragic—Ryland had made restaurant history in a state once better known for red sauce joints and boardwalk grub. The rebirth of the Ryland Inn a year ago, a vision realized by new owners Jeanne and Frank Cretella, with chef Anthony Bucco, gives us a very shiny new dining toy.

long commute to their new five-bedroom homes on two acres over for the day, there’s a smattering of casual dinner-seekers finishing burgers, there are journalists like me, in between night meetings, stopping in to catch the local gossip in a homey, low-key setting. That Ryland’s a roadhouse, a pitstop on the outskirts of suburbia. By the time it was purchased and re-imagined as a fine-dining destination, with Dennis Foy briefly installed as the name chef—a front man for then-little-known Craig Shelton—Readington and eastern Hunterdon had sprawled confidently into suburbia and many of the denizens in the immediate ‘hood (not to mention surrounding hunt country) were well-heeled and world-wise, ready for haute cuisine in an atmosphere to match, right in their backyards. The 1990s Ryland Inn delivered it all. Soon Shelton was on the cover of Gourmet magazine and the recipient of the food world’s equivalent of an Oscar, a James Beard Award. Ryland catered to the food cognoscente and captains of industry in a seamless operation that defied anything New Jersey had seen. Though its last years were rocky—and the flood that six years ago forced the inn to close was tragic—Ryland had made restaurant history in a state once better known for red sauce joints and boardwalk grub. The rebirth of the Ryland Inn a year ago, a vision realized by new owners Jeanne and Frank Cretella, with chef Anthony Bucco, gives us a very shiny new dining toy.

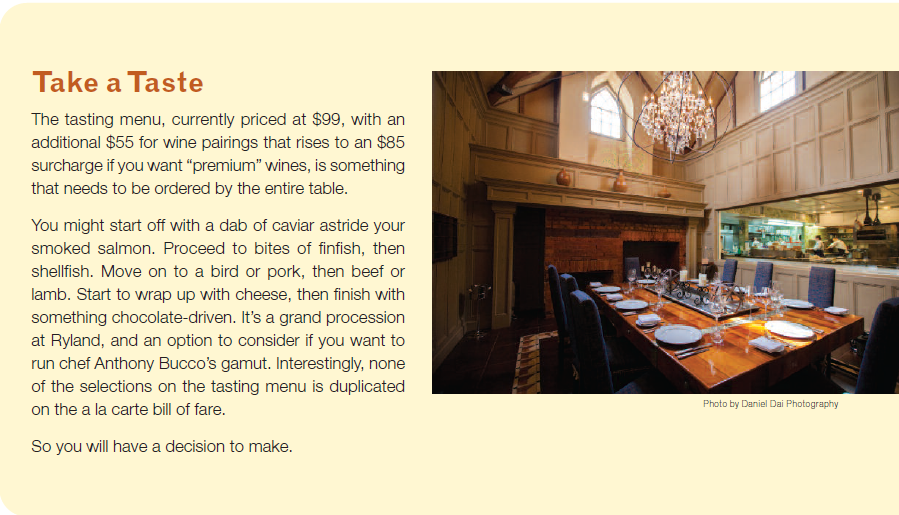

Today’s Ryland is posh, suave and ready for parties.  The outdoor entryway that leads to the indoor entryway just about shouts “Have your wedding here!” Once inside, vaulted ceilings, chandeliers that look like they were recycled from Liz Taylor’s diamond booty, fabrics and appointments hardly from the off-the-rack collections, and an air of mission accomplished set the scene for rarefied dining. Rather than a pretty charger plate that will be swept away shortly after you’re seated, there’s a framed picture at your place setting. Something old to add to all the new, I suspect. The Cretellas clearly wanted to bring every aspect of Ryland’s past to its high-toned present, and so there’s a sense of history in the artwork as well as in the Old-World graciousness of the well-orchestrated service. Come to Ryland to be pampered, once again.

The outdoor entryway that leads to the indoor entryway just about shouts “Have your wedding here!” Once inside, vaulted ceilings, chandeliers that look like they were recycled from Liz Taylor’s diamond booty, fabrics and appointments hardly from the off-the-rack collections, and an air of mission accomplished set the scene for rarefied dining. Rather than a pretty charger plate that will be swept away shortly after you’re seated, there’s a framed picture at your place setting. Something old to add to all the new, I suspect. The Cretellas clearly wanted to bring every aspect of Ryland’s past to its high-toned present, and so there’s a sense of history in the artwork as well as in the Old-World graciousness of the well-orchestrated service. Come to Ryland to be pampered, once again.

The menu divined by Bucco is a coming together of contemporary cooking. He trends seasonal, adds a little local, and comes up with American Med as a core. You can expect pears and pumpkin in fall, Jersey staples such as birds from Griggstown Farm and fish from Barnegat, and also luxe ingredients the revived Ryland wants attached to its name: foie gras, Berkshire pork, uni. The cavalcade of chi-chi ingredients punctuates the menu, some of them a tad out-of-date (squid ink, white anchovies), some of them more current (red quinoa, shishito peppers). You can go a la carte, you can go tasting menu; you will spend. All entrees are in the $30s, the least expensive starter a salad at $12. Indeed, the wine list struggles at the value end of the spectrum and could stand to be updated at the three-figure range as well with a smarter selection of artisan bottles. But we enjoy our splurge, cosseted as we are in the grand Polo Room, and dispatch a complimentary uni-custard with smiles. I’m feeling quite at home with the Jersey’d version of pasta carbonara, a tangle of squid ink chitarra with ultra-smoky Mangalitsa bacon, spirited Fresno chilies and a dot or five of uni.

It’s mod and classic at the same time and, most importantly, it’s delicious. So is the stately torchon of foie gras, swaddled with pears braised in vanilla and an onion jam I’d be happy to have for dessert. There’s even a dusting of chocolate crumbs to make my case for this starter as a most grand finale. The octopus done Spanish style is terrific, an assemblage of tender meat with crumbles of warming chorizo, those vivacious shishitos, real-deal black potatoes and a kick of zesty chimichurri. Bring it on, anytime. By contrast, the mild purée of fall vegetables is a bland option, but that isn’t to say this take on a stylish soup is uninteresting: with twirls of fennel fronds, a smack of fig jam and a sprinkling of pumpkin seed oil, it’s both comforting and appropriately warming. Our server tosses in an extra, a black olive cavatelli that strikes me as pure Sicily with its dressing of golden raisin puree kept in check by good, salty capers and buttery pine nuts. Just when I think Bucco is too reliant on sweet, he proves his mettle with a shot of the right balancing agent. The harissa-stoked tomato jam is as fine a friend as grilled swordfish can have, the sweet-hot condiment giving a needed tickle to the rich fish steak. I don’t think the red quinoa or eggplant on the dish did as spirited a two-step with the meaty sword, however.

But I love the way the chickpea panisse and riffs of white anchovies play off the steamed red snapper, and thought the spark of lemon basil and snap of skinny string beans kept pace with the plate. Pork belly, especially Hudson Valley Berkshire, took a liking to the cheerful crumb-like topping the folks here dub “granola,” and the tart apple and mild butternut squash accompaniments were just-right sides. Desserts trip the globe, but need reining in at times. The yuzu curd “truffle,” with astringent Asian pear, a sultry black sesame cake and green tea ice cream works a Far East theme nicely. But flavors warred in the frozen cranberry parfait, with pecan streusel, toasted marshmallow meringue and cloying pumpkin pie ice cream proving too much that’s too sweet isn’t a good thing. The central taste of cranberry was lost. Tamarind, however, was a uniting element in the peanut butter mousse ensemble that allowed specks of banana and dabs of Nutella to compliment, not cover up. Ryland, rebooted for an era that knows both unbridled luxury and forced restraint. Wow, I think as I leave the space I first set foot in 36 years ago. Lots of bucks have been put into this ol’ gal, and she’s looking mighty fine. Over the top? Maybe. But not out of sight.

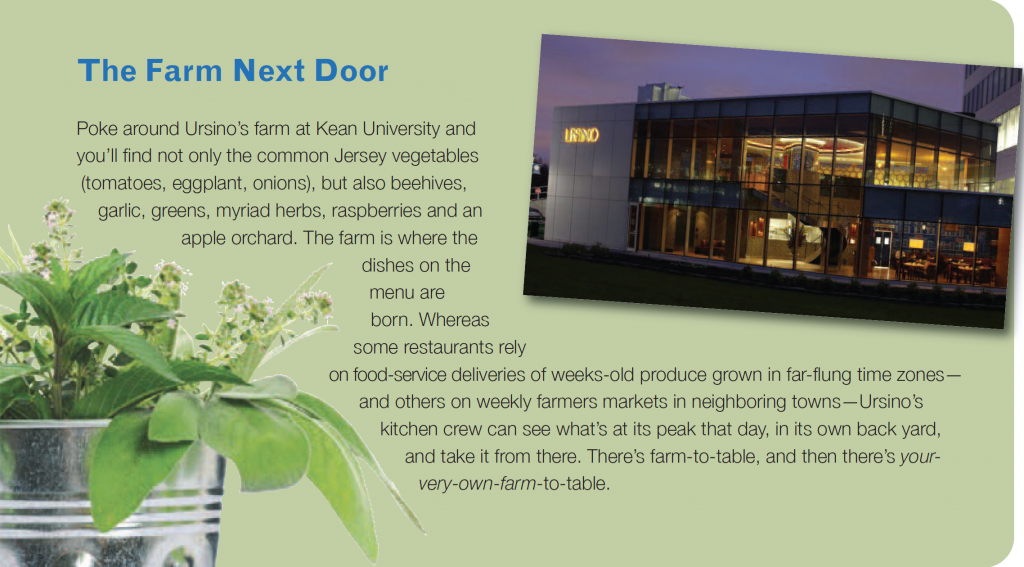

Turso’s menu reflects what’s grown by Dreyer and his farm crew. The menu descriptions, while referring to the origins of ingredients such as Barnegat scallops and “local” oysters, all but ignored this extraordinary plus. For instance, Liberty Hall beet salad, with its richly colored baby carrots, nibs of honeyed walnuts and sparks of sharp Valley Shepherd cheese, was a rousing harbinger of autumn on this latesummer night. Yet nowhere is it explained that Liberty Hall is both the name of one of Kean’s campuses and a history museum, originally the elegant home of New Jersey’s first governor. (You’d think an education would be part of the dining package.) We had to ask about almost everything, and waits between questions and answers often were long. On the other hand, Turso’s focused, uncomplicated food doesn’t need a promotional boost. Slice into the smoked swordfish, smartly partnered with shavings of crunchy fennel and perky pea tendrils, and you’ll quickly be distracted from service flaws by flavor rhythms of the rich fish as it intersects with a smack of anise from the fennel and the engaging rawness of the shoots.

Turso’s menu reflects what’s grown by Dreyer and his farm crew. The menu descriptions, while referring to the origins of ingredients such as Barnegat scallops and “local” oysters, all but ignored this extraordinary plus. For instance, Liberty Hall beet salad, with its richly colored baby carrots, nibs of honeyed walnuts and sparks of sharp Valley Shepherd cheese, was a rousing harbinger of autumn on this latesummer night. Yet nowhere is it explained that Liberty Hall is both the name of one of Kean’s campuses and a history museum, originally the elegant home of New Jersey’s first governor. (You’d think an education would be part of the dining package.) We had to ask about almost everything, and waits between questions and answers often were long. On the other hand, Turso’s focused, uncomplicated food doesn’t need a promotional boost. Slice into the smoked swordfish, smartly partnered with shavings of crunchy fennel and perky pea tendrils, and you’ll quickly be distracted from service flaws by flavor rhythms of the rich fish as it intersects with a smack of anise from the fennel and the engaging rawness of the shoots.

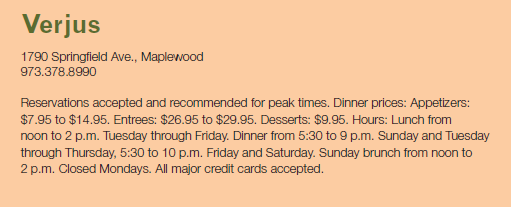

business, and where it might be taken more seriously than at any other restaurant in New Jersey. This is serious praise. The chef-owner Charles Tutino knows his birds. He not only roasts chickens every day Verjus is open, he roasts duck. Both often come in half-bird portions, which may seem an extreme amount of food to anyone who is not an aficionado of expertly roasted birds. The only reason I’ve ever found to stop eating once a roasted chicken (or duck) is set before me is to save something for the next day’s lunch. This requires belief in the benefits and joys of delayed gratification. When the bird is properly roasted, that is not always possible. It was not possible at Verjus. Let’s back up a bit, and give you some background as well as appetizers. Tutino is a classically trained chef who worked at French restaurants in New York before coming to New Jersey and setting up shop with his wife Jane Witkin in an understated space they decorated in a style that would mirror the food. There are cloth-covered tables, dark blond wood chairs, silver and stemmed glasses. There are, perhaps, a couple dozen tables. The scene is hushed, adult. You can converse.

business, and where it might be taken more seriously than at any other restaurant in New Jersey. This is serious praise. The chef-owner Charles Tutino knows his birds. He not only roasts chickens every day Verjus is open, he roasts duck. Both often come in half-bird portions, which may seem an extreme amount of food to anyone who is not an aficionado of expertly roasted birds. The only reason I’ve ever found to stop eating once a roasted chicken (or duck) is set before me is to save something for the next day’s lunch. This requires belief in the benefits and joys of delayed gratification. When the bird is properly roasted, that is not always possible. It was not possible at Verjus. Let’s back up a bit, and give you some background as well as appetizers. Tutino is a classically trained chef who worked at French restaurants in New York before coming to New Jersey and setting up shop with his wife Jane Witkin in an understated space they decorated in a style that would mirror the food. There are cloth-covered tables, dark blond wood chairs, silver and stemmed glasses. There are, perhaps, a couple dozen tables. The scene is hushed, adult. You can converse.

Frank, who legend has it wanted to be buried with a slice of owner Louise Esposito’s banana cream pie, who knew the secret behind the name of the world-renowned restaurant, and who just might be its unofficial mascot, invariably greets diners who descend into the basement and keeps crooning all night long. Those diners might be Jay-Z and Beyonce. They might be members of the cast of The Sopranos. They might be sports stars. They might be good old Jersey boy rock stars such as Jon Bon Jovi. You don’t believe these folks, plus heads of state and of Fortune 500 companies, hurdle the hoops of the reservation process to score a table in the cramped, cluttered, completely charismatic low-ceilinged, dimly lit dining spaces where vintage Italian nonna fare is served alongside a handful of improbable-sounding original Esposito dishes? They do.

Frank, who legend has it wanted to be buried with a slice of owner Louise Esposito’s banana cream pie, who knew the secret behind the name of the world-renowned restaurant, and who just might be its unofficial mascot, invariably greets diners who descend into the basement and keeps crooning all night long. Those diners might be Jay-Z and Beyonce. They might be members of the cast of The Sopranos. They might be sports stars. They might be good old Jersey boy rock stars such as Jon Bon Jovi. You don’t believe these folks, plus heads of state and of Fortune 500 companies, hurdle the hoops of the reservation process to score a table in the cramped, cluttered, completely charismatic low-ceilinged, dimly lit dining spaces where vintage Italian nonna fare is served alongside a handful of improbable-sounding original Esposito dishes? They do. didn’t fly in because even the leftovers couldn’t fit in an airplane’s overhead compartment, pasta awash in a “blush” sauce that combines ricotta and marinara, and Louise Esposito’s pies, each of which—and there are a good couple dozen—have their own ardent legions of fans. I’ll throw my support behind the coconut-pecan ricotta pie, but we’ll discuss later. First, the hype surrounding Chef Vola’s is exaggerated. Yes, the phone number remains unlisted in a phone-book sense of listing numbers. But you have it here and you can find it if you have basic-level Internet skills. Second, you can get a reservation. As with many extremely popular restaurants, you simply have to plan ahead, call ahead and not expect a table at 8 on a Saturday night.

didn’t fly in because even the leftovers couldn’t fit in an airplane’s overhead compartment, pasta awash in a “blush” sauce that combines ricotta and marinara, and Louise Esposito’s pies, each of which—and there are a good couple dozen—have their own ardent legions of fans. I’ll throw my support behind the coconut-pecan ricotta pie, but we’ll discuss later. First, the hype surrounding Chef Vola’s is exaggerated. Yes, the phone number remains unlisted in a phone-book sense of listing numbers. But you have it here and you can find it if you have basic-level Internet skills. Second, you can get a reservation. As with many extremely popular restaurants, you simply have to plan ahead, call ahead and not expect a table at 8 on a Saturday night.

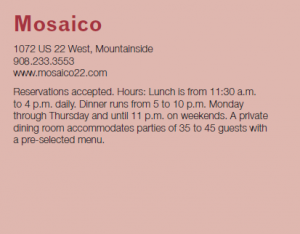

Mosaico. “A mosaic is made up of a thousand little details that are individually beautiful and of high quality,” says Carrera. “The artist assembles them to form a complete picture. We just reassembled some of the pieces.”

Mosaico. “A mosaic is made up of a thousand little details that are individually beautiful and of high quality,” says Carrera. “The artist assembles them to form a complete picture. We just reassembled some of the pieces.” creation of chef Luis Romero (who has been cooking for Carrera and Dinic for more than a decade) is a scallopine layered with portabella mushrooms, roasted peppers and gorgonzola, in a brandy brown sauce, served with red potatoes on a bed of arugula. Another standout item is the French cut grilled pork chop. It has an entirely different thickness than what New Jersey restaurant-goers are probably used to. It’s never dry, even when ordered well done. Mosaico has also carved out a sterling reputation as a place to enjoy the bounty of the ocean. There are always at least two fish specials on the menu, even at lunch. Regulars swear by the crab cakes and, according to Carrera, the seafood salad rivals prosciutto and melon as their most popular appetizer. Grilled calamari is not on the menu, but is listed among the specials almost every day. Fish and shellfish are delivered each morning, so there’s an excellent chance that what comes to the table was swimming somewhere the previous day. The crowd at Mosaico is a mosaic in and of itself. At midday, four out of five tables appear to be business lunches. Some tables tear through their meals, while others linger well

creation of chef Luis Romero (who has been cooking for Carrera and Dinic for more than a decade) is a scallopine layered with portabella mushrooms, roasted peppers and gorgonzola, in a brandy brown sauce, served with red potatoes on a bed of arugula. Another standout item is the French cut grilled pork chop. It has an entirely different thickness than what New Jersey restaurant-goers are probably used to. It’s never dry, even when ordered well done. Mosaico has also carved out a sterling reputation as a place to enjoy the bounty of the ocean. There are always at least two fish specials on the menu, even at lunch. Regulars swear by the crab cakes and, according to Carrera, the seafood salad rivals prosciutto and melon as their most popular appetizer. Grilled calamari is not on the menu, but is listed among the specials almost every day. Fish and shellfish are delivered each morning, so there’s an excellent chance that what comes to the table was swimming somewhere the previous day. The crowd at Mosaico is a mosaic in and of itself. At midday, four out of five tables appear to be business lunches. Some tables tear through their meals, while others linger well  into the afternoon. In the evenings, it’s a blend of young and old, family dinners and romantic twosomes, and a fair number of business people.

into the afternoon. In the evenings, it’s a blend of young and old, family dinners and romantic twosomes, and a fair number of business people.

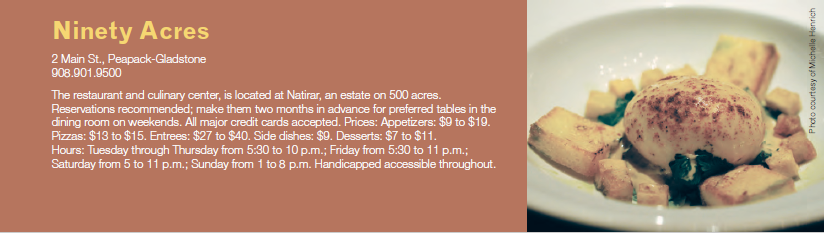

the service staff debated right in front of us which table got the plates they had in hand; politely trying to wrangle silverware as our food grew cold; and having to beg refills of our wine from a bottle set at a distance. The worst offenders? A couple of captains who openly complained about being short-staffed. None of that happened during a recent visit, when our meal’s delivery was well-orchestrated and servers attentive (if still prone to interrupting conversation with the always-awkward, “How is everything?”). The wine list has grown in scope and depth, the handiwork of sommelier Brooke Sabel. Though the by-the-glass program could offer more boutique selections, there’s a tie to the cuisine that shows thought. Clearly, Ninety Acres is in this game for the long haul.

the service staff debated right in front of us which table got the plates they had in hand; politely trying to wrangle silverware as our food grew cold; and having to beg refills of our wine from a bottle set at a distance. The worst offenders? A couple of captains who openly complained about being short-staffed. None of that happened during a recent visit, when our meal’s delivery was well-orchestrated and servers attentive (if still prone to interrupting conversation with the always-awkward, “How is everything?”). The wine list has grown in scope and depth, the handiwork of sommelier Brooke Sabel. Though the by-the-glass program could offer more boutique selections, there’s a tie to the cuisine that shows thought. Clearly, Ninety Acres is in this game for the long haul.

horseradish. At a nearby table, a party of smartly dressed adults and children were doing Ninety Acres’ Saturday night special of prime rib, exchanging grins and wielding their steak knives with admirable skill. Food for thought. Finales here follow suit, meaning they are neither splashy nor curiosities, but takes on classic confections. My favorite was the mascarpone cheesecake that may have skirted pledges to seasonality with roasted pear and rosemary honey as accents, but charmed with pure deliciousness. The crust of the maple custard pie was short of perfectly flaky, but the tout to local eggs and the fledgling sugaring industry can’t be shortchanged. There’s also a chocolate torte paired with chocolate-jalapeno ice cream that shouldn’t put off anyone who fears the heat of chilies. It’s a barely-there presence, that jalapeno, making the dessert all about chocolate. Ninety Acres is all about the New Jersey the jokesters ignore—the New Jersey, mind you, we’re grateful they ignore. It’s been described by those who don’t live here as an oasis. But it’s not. Natirar and its restaurant reflect the well-mannered elegance of the Somerset Hills. It’s going to be a pleasure to watch Ninety Acres and its surrounding communities explore new culinary horizons together.

horseradish. At a nearby table, a party of smartly dressed adults and children were doing Ninety Acres’ Saturday night special of prime rib, exchanging grins and wielding their steak knives with admirable skill. Food for thought. Finales here follow suit, meaning they are neither splashy nor curiosities, but takes on classic confections. My favorite was the mascarpone cheesecake that may have skirted pledges to seasonality with roasted pear and rosemary honey as accents, but charmed with pure deliciousness. The crust of the maple custard pie was short of perfectly flaky, but the tout to local eggs and the fledgling sugaring industry can’t be shortchanged. There’s also a chocolate torte paired with chocolate-jalapeno ice cream that shouldn’t put off anyone who fears the heat of chilies. It’s a barely-there presence, that jalapeno, making the dessert all about chocolate. Ninety Acres is all about the New Jersey the jokesters ignore—the New Jersey, mind you, we’re grateful they ignore. It’s been described by those who don’t live here as an oasis. But it’s not. Natirar and its restaurant reflect the well-mannered elegance of the Somerset Hills. It’s going to be a pleasure to watch Ninety Acres and its surrounding communities explore new culinary horizons together.

THERESA’S The always-smart partnership of shellfish and beans makes for a simple, yet engaging starter. Shrimp are marinated, then grilled, and plated with a white bean salad. The pair is united by a sweet flash of roasted red pepper and the herbal kick of a pesto-laced oil. Flashy and fussy? No. Soulful and satisfying? Yes. So is a local favorite pasta dish, the now-classic penne with vodka sauce. It’s so often tired and trite, laden with massive amounts of sauce that prompt giggles among teens, who think they’ll get a buzz from a sauce labeled “vodka.” Sorry. There’s a vaguely astringent quality to the spirited sauce, but what gives Theresa’s version of the dish a lift above the norm is the carbonara-like addition of crumbled pancetta and sweet peas. Potent in a non-alcoholic way. It’s possible that riots would ensue in genteel Westfield if the asiago-crusted chicken ever were taken off Theresa’s menu. Our polite server on this night said there was no chance of that. Folks love the cheese-on-cheese aspect of the dish, what with mozzarella layered in the mix. It’s all balanced by a dose of tomato and a garlicky cream sauce. If you’re looking for a sweet-tart sensation, give the balsamic-and apricot-glazed pork tenderloin a go. It’s got the appeal of something barbecued as well as a couple of hearty standbys on the side in garlic-licked mashed potatoes and a tangle of spinach. The dessert of choice? A dense, yet light, flourless chocolate cake that demands, and receives, a dollop of vanilla gelato.

THERESA’S The always-smart partnership of shellfish and beans makes for a simple, yet engaging starter. Shrimp are marinated, then grilled, and plated with a white bean salad. The pair is united by a sweet flash of roasted red pepper and the herbal kick of a pesto-laced oil. Flashy and fussy? No. Soulful and satisfying? Yes. So is a local favorite pasta dish, the now-classic penne with vodka sauce. It’s so often tired and trite, laden with massive amounts of sauce that prompt giggles among teens, who think they’ll get a buzz from a sauce labeled “vodka.” Sorry. There’s a vaguely astringent quality to the spirited sauce, but what gives Theresa’s version of the dish a lift above the norm is the carbonara-like addition of crumbled pancetta and sweet peas. Potent in a non-alcoholic way. It’s possible that riots would ensue in genteel Westfield if the asiago-crusted chicken ever were taken off Theresa’s menu. Our polite server on this night said there was no chance of that. Folks love the cheese-on-cheese aspect of the dish, what with mozzarella layered in the mix. It’s all balanced by a dose of tomato and a garlicky cream sauce. If you’re looking for a sweet-tart sensation, give the balsamic-and apricot-glazed pork tenderloin a go. It’s got the appeal of something barbecued as well as a couple of hearty standbys on the side in garlic-licked mashed potatoes and a tangle of spinach. The dessert of choice? A dense, yet light, flourless chocolate cake that demands, and receives, a dollop of vanilla gelato.

MOJAVE GRILL There was a special soup on tap the night of our visit that intrigued: caramelized onion and potato, punctuated by the freshness of scallions and topped with crisped onions that have been shot through with cayenne. Of all the Scalera concepts, I’ve liked Mojave the best. There’s bolder seasoning and more of a distinctive personality on the plates, particularly on the specials’ roster. This soup crystallizes why?: The onion-potato soup is thick, rich and calls for counterpoint, which it gets in the rawness of the scallions and the heat of the crunchy cayenne’d onions. The signature black bean soup needs its jalapeno spike, as well as the luxurious lime crema, chunks of avocado and chopped, spiced tomato. Extra dimension in a dish

MOJAVE GRILL There was a special soup on tap the night of our visit that intrigued: caramelized onion and potato, punctuated by the freshness of scallions and topped with crisped onions that have been shot through with cayenne. Of all the Scalera concepts, I’ve liked Mojave the best. There’s bolder seasoning and more of a distinctive personality on the plates, particularly on the specials’ roster. This soup crystallizes why?: The onion-potato soup is thick, rich and calls for counterpoint, which it gets in the rawness of the scallions and the heat of the crunchy cayenne’d onions. The signature black bean soup needs its jalapeno spike, as well as the luxurious lime crema, chunks of avocado and chopped, spiced tomato. Extra dimension in a dish  is why we eat out, so we can experience what we might not do for ourselves at home. We tend not to make tuna ceviche at home very often, either, which is why Mojave’s faithful snag the chunks of yellowfin made brazen by ginger and pasilla chilies and then soothed by cooling cucumbers and avocado. Tune into the pulled chicken enchiladas and, if you’re in the mood for comfort food, for the ancho mole, red rice and black beans with a swath of cotija cheese and sultry crema. They’re just about as harmonic as a chorus from The Mamas and The Papas. If you’re craving quesadillas, nab the blackened chicken number that comes cosseted with a Monterey Jack-esque cheese and a generous slather of avocado-basil aioli. I wasn’t taken with the yucca-crusted grouper, a nightly special, for the grouper was overcooked, the taste of the yucca not doing a thing for the fish, and the red pepper puree overwhelming. The one-two punch of seared flank steak topped with a vigorous chimichurri hit on all cylinders, though—and it just might make you whip up your own take on the parsley-garlic-hot pepper-vinegar sauce this summer when you’re grilling a flank steak in your backyard.

is why we eat out, so we can experience what we might not do for ourselves at home. We tend not to make tuna ceviche at home very often, either, which is why Mojave’s faithful snag the chunks of yellowfin made brazen by ginger and pasilla chilies and then soothed by cooling cucumbers and avocado. Tune into the pulled chicken enchiladas and, if you’re in the mood for comfort food, for the ancho mole, red rice and black beans with a swath of cotija cheese and sultry crema. They’re just about as harmonic as a chorus from The Mamas and The Papas. If you’re craving quesadillas, nab the blackened chicken number that comes cosseted with a Monterey Jack-esque cheese and a generous slather of avocado-basil aioli. I wasn’t taken with the yucca-crusted grouper, a nightly special, for the grouper was overcooked, the taste of the yucca not doing a thing for the fish, and the red pepper puree overwhelming. The one-two punch of seared flank steak topped with a vigorous chimichurri hit on all cylinders, though—and it just might make you whip up your own take on the parsley-garlic-hot pepper-vinegar sauce this summer when you’re grilling a flank steak in your backyard. As I scooped up the last of the spiced walnuts in the orange-and-arugula salad at ISABELLA’S, I sensed an impatience on the part of my dining companion. It took no special powers of deduction for me to realize my pal wanted our bacon- Cheddar meatloaf now. It soon arrived and began to disappear. I managed to score two bites and reasonable enough spoonfuls of mashed potatoes and creamed spinach, both of which benefit from gravy chunky with shallots. You’d think meatloaf is only served in this country when the moon is full on a fourth Tuesday the way some people attack slices of the stuff. There’s no denying the appeal of Isabella’s meatloaf. (Which has a lot to do with an abundance of bacon, I suspect.) While the attack on the meatloaf was taking place, I took advantage of an uninterrupted spell communing with the night’s special ravioli: pasta pockets stuffed with goat cheese and roasted red peppers, then drizzled with a vibrant tomato-pesto sauce. There’s an accord reached on the fettuccine tossed

As I scooped up the last of the spiced walnuts in the orange-and-arugula salad at ISABELLA’S, I sensed an impatience on the part of my dining companion. It took no special powers of deduction for me to realize my pal wanted our bacon- Cheddar meatloaf now. It soon arrived and began to disappear. I managed to score two bites and reasonable enough spoonfuls of mashed potatoes and creamed spinach, both of which benefit from gravy chunky with shallots. You’d think meatloaf is only served in this country when the moon is full on a fourth Tuesday the way some people attack slices of the stuff. There’s no denying the appeal of Isabella’s meatloaf. (Which has a lot to do with an abundance of bacon, I suspect.) While the attack on the meatloaf was taking place, I took advantage of an uninterrupted spell communing with the night’s special ravioli: pasta pockets stuffed with goat cheese and roasted red peppers, then drizzled with a vibrant tomato-pesto sauce. There’s an accord reached on the fettuccine tossed  with baby shrimp, corn, sweet peas, sundried tomatoes and mushrooms, all of which is bound by a chipotle-charged cream sauce. This is vintage Scalera and what I think his restaurants do best: Take a bunch of familiar ingredients, a concept that’s not off-putting, then jazz it all up to the level of food you expect when you go out to eat. My wish for Isabella’s? That it would pair a cut of beef other than filet mignon with a crust of peppercorns. That intense coating would work much better with a chewier, heartier flavor, such as strip steak or rib-eye, than it does with a mildmannered filet. But all ends well here with a banana-studded bread pudding streaked with caramel and served with vanilla ice cream. It usually does at Westfield’s trio of winners. EDGE

with baby shrimp, corn, sweet peas, sundried tomatoes and mushrooms, all of which is bound by a chipotle-charged cream sauce. This is vintage Scalera and what I think his restaurants do best: Take a bunch of familiar ingredients, a concept that’s not off-putting, then jazz it all up to the level of food you expect when you go out to eat. My wish for Isabella’s? That it would pair a cut of beef other than filet mignon with a crust of peppercorns. That intense coating would work much better with a chewier, heartier flavor, such as strip steak or rib-eye, than it does with a mildmannered filet. But all ends well here with a banana-studded bread pudding streaked with caramel and served with vanilla ice cream. It usually does at Westfield’s trio of winners. EDGE  Editor’s Note: Andy Clurfield is a former editor of Zagat New Jersey. The longtime food critic for the Asbury Park Press also has been published in Gourmet, Saveur and Town & Country, and on epicurious.com.

Editor’s Note: Andy Clurfield is a former editor of Zagat New Jersey. The longtime food critic for the Asbury Park Press also has been published in Gourmet, Saveur and Town & Country, and on epicurious.com.

mble restaurant where local favorites are served. Frank Rizzo, chef-owner of The Italian Pantry Bistro, follows through on all the promises made in the restaurant’s name on his menu—in his cooking and in the attitude set forth in this small, near-Spartan storefront in downtown Cranford. “Comfort” may have become a gastronomic cliché, yet Rizzo and his crew disregard it as a sound-bite and wend their way around its possibilities with confidence and a smack of creativity. All that makes Italian Pantry a fun place to dig in to hearty grub. Which is why this BYOB is crowded from the ring of the dinner bell ’til last call from the kitchen. And why families, kids in tow, can be spotted doing early-shift eating—and couples catching a casual-dress date night knock wineglasses in twosomes and foursomes later on. For all its popularity in Union County, it flies under the radar of many of New Jersey’s restaurant groupies. That might be because it is devoted to the now-rather-passé Comfort Food category. Yet I’d bet a bite of sage-tinged French toast, in full fall regalia with the flavors of poached pear, red onion and a pungent blue cheese sauce, might tempt those trackers of trends. I know the baby-back ribs could stand against anything a destination barbecue shack in the South might be dishing up. You could rack up the clichés describing them—falling off the bone, licked with sauce neither too tart nor too sugared—but the point is the sincerity of the preparation. And, absolutely, the pert, moist, just-shy-of-sturdy cornbread served on the side. You could spend a lot of time wondering why you might never before have come across a sweet potato dumpling. Gently kneaded flour-water dough is plied into myriad shapes and stuffed with all manner of fillings the world over, but the marriage of petite fried turnover and mashed sweet potato is rare. It shouldn’t be. Especially if a swirl of chive oil is used as a spirited accent as it is here. Crunchy calamari with a tomato fondue reads like a signature dish for a restaurant called The Italian Pantry Bistro. But it was the weak link in the opening rounds, with too-tough squid giving off too much frying oil and a dipping sauce that needed to pack more of a spice punch. You’ll expect—and you’ll get—burgers, pizzas and pastas in this hometown-proud spot. But there’s always a twist, or a hint of something extra. It might be a “Buffalo”-style burger paying homage to that city’s famous Anchor Bar wings, slathered as it is with blue cheese. Or a beefy patty that’s another trip to the South, with Tennessee bacon, mushrooms, onions, Cheddar and a slap of that excellent house barbecue sauce. There’s a hint of truffle oil, a substance I usually dread, in the mix, but it’s a background note. Personal-size (jumbo personal-size, th

mble restaurant where local favorites are served. Frank Rizzo, chef-owner of The Italian Pantry Bistro, follows through on all the promises made in the restaurant’s name on his menu—in his cooking and in the attitude set forth in this small, near-Spartan storefront in downtown Cranford. “Comfort” may have become a gastronomic cliché, yet Rizzo and his crew disregard it as a sound-bite and wend their way around its possibilities with confidence and a smack of creativity. All that makes Italian Pantry a fun place to dig in to hearty grub. Which is why this BYOB is crowded from the ring of the dinner bell ’til last call from the kitchen. And why families, kids in tow, can be spotted doing early-shift eating—and couples catching a casual-dress date night knock wineglasses in twosomes and foursomes later on. For all its popularity in Union County, it flies under the radar of many of New Jersey’s restaurant groupies. That might be because it is devoted to the now-rather-passé Comfort Food category. Yet I’d bet a bite of sage-tinged French toast, in full fall regalia with the flavors of poached pear, red onion and a pungent blue cheese sauce, might tempt those trackers of trends. I know the baby-back ribs could stand against anything a destination barbecue shack in the South might be dishing up. You could rack up the clichés describing them—falling off the bone, licked with sauce neither too tart nor too sugared—but the point is the sincerity of the preparation. And, absolutely, the pert, moist, just-shy-of-sturdy cornbread served on the side. You could spend a lot of time wondering why you might never before have come across a sweet potato dumpling. Gently kneaded flour-water dough is plied into myriad shapes and stuffed with all manner of fillings the world over, but the marriage of petite fried turnover and mashed sweet potato is rare. It shouldn’t be. Especially if a swirl of chive oil is used as a spirited accent as it is here. Crunchy calamari with a tomato fondue reads like a signature dish for a restaurant called The Italian Pantry Bistro. But it was the weak link in the opening rounds, with too-tough squid giving off too much frying oil and a dipping sauce that needed to pack more of a spice punch. You’ll expect—and you’ll get—burgers, pizzas and pastas in this hometown-proud spot. But there’s always a twist, or a hint of something extra. It might be a “Buffalo”-style burger paying homage to that city’s famous Anchor Bar wings, slathered as it is with blue cheese. Or a beefy patty that’s another trip to the South, with Tennessee bacon, mushrooms, onions, Cheddar and a slap of that excellent house barbecue sauce. There’s a hint of truffle oil, a substance I usually dread, in the mix, but it’s a background note. Personal-size (jumbo personal-size, th at is) pizzas (here, called pizzettas) aren’t the corner takeout kind. We took to the potato-onion-mascarpone pie, loving its charred crust and light-on-the-toppings style. I would’ve liked it even more with a more generous sprinkle of big-flake sea salt. Something to think about. That pizzetta offered a better use of the spud than the potato gnocchi, which weighed heavy in a terrific pumpkin beurre fondue sporting crispy fried sage leaves. That combo of high-fall pumpkin and butter has potential galore. You’ll see another riff on often-tired comfort fare in Rizzo’s chicken pot pie, which is topped with cornbread instead of either pastry or biscuit. It has all the usual suspects within (chicken chunks, mushrooms, peas, carrots) and a soothing gravy to bind it all together. Johnny Blue mussels, however, are anything but predictable. This season, the kitchen’s playing the pumpkin theme big, and it sets the bivalves in a startling sauce of pumpkin dotted with flecks of cranberries. It seems discordant at first, that swash of mildly sweet sauce with mussels, but there’s something funky and fun about the pairing. And the stand-up fries on the side don’t mind the frivolity. You guessed right: There’s a cupcake on the dessert menu. On this night, it’s a mini sweet potato number dressed in toasted marshmallow frosting. It’s fit for Thanksgiving. I had to laugh, eating one, as I imagined Rizzo and his kitchen team devising it as a spoof to all those marshmallow-topped sweet potato casseroles on holiday tables. Less satisfying was a baked apple dumpling that lacked substantial apple presence and seemed to try to compensate with too much walnut-raisin stuffing and a burst of butterscotch sauce. But a well-balanced poached pear crème brulée with a properly crusted top hit its stride, and the high mark for finales. The Italian Pantry Bistro is a neighborhood restaurant with a voice. It’s deliberately modest and humble, like many storefront BYOBs, but it doesn’t run with the pack by playing it safe with familiar dishes. No, instead, Italian Pantry spins comfort in a way that makes it impossible to take the genre for granted. EDGE

at is) pizzas (here, called pizzettas) aren’t the corner takeout kind. We took to the potato-onion-mascarpone pie, loving its charred crust and light-on-the-toppings style. I would’ve liked it even more with a more generous sprinkle of big-flake sea salt. Something to think about. That pizzetta offered a better use of the spud than the potato gnocchi, which weighed heavy in a terrific pumpkin beurre fondue sporting crispy fried sage leaves. That combo of high-fall pumpkin and butter has potential galore. You’ll see another riff on often-tired comfort fare in Rizzo’s chicken pot pie, which is topped with cornbread instead of either pastry or biscuit. It has all the usual suspects within (chicken chunks, mushrooms, peas, carrots) and a soothing gravy to bind it all together. Johnny Blue mussels, however, are anything but predictable. This season, the kitchen’s playing the pumpkin theme big, and it sets the bivalves in a startling sauce of pumpkin dotted with flecks of cranberries. It seems discordant at first, that swash of mildly sweet sauce with mussels, but there’s something funky and fun about the pairing. And the stand-up fries on the side don’t mind the frivolity. You guessed right: There’s a cupcake on the dessert menu. On this night, it’s a mini sweet potato number dressed in toasted marshmallow frosting. It’s fit for Thanksgiving. I had to laugh, eating one, as I imagined Rizzo and his kitchen team devising it as a spoof to all those marshmallow-topped sweet potato casseroles on holiday tables. Less satisfying was a baked apple dumpling that lacked substantial apple presence and seemed to try to compensate with too much walnut-raisin stuffing and a burst of butterscotch sauce. But a well-balanced poached pear crème brulée with a properly crusted top hit its stride, and the high mark for finales. The Italian Pantry Bistro is a neighborhood restaurant with a voice. It’s deliberately modest and humble, like many storefront BYOBs, but it doesn’t run with the pack by playing it safe with familiar dishes. No, instead, Italian Pantry spins comfort in a way that makes it impossible to take the genre for granted. EDGE  The Italian Pantry Bistro 13 Eastman St., Cranford 908.272.7790 Open from 11:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday, from 11:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. Friday and Saturday, and from 5 to 9 p.m. Sunday. Closed Mondays. Reservations accepted for Sunday, Tuesday through Thursday only; it’s first-come, first-served on Fridays and Saturdays. All major credit cards accepted. BYOB. Appetizers generally range from $8 to $14, burgers $13 to $14, pizzas from $9 to $14 and pastas $20 and up. Entrees are $22 to $32.

The Italian Pantry Bistro 13 Eastman St., Cranford 908.272.7790 Open from 11:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday, from 11:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. Friday and Saturday, and from 5 to 9 p.m. Sunday. Closed Mondays. Reservations accepted for Sunday, Tuesday through Thursday only; it’s first-come, first-served on Fridays and Saturdays. All major credit cards accepted. BYOB. Appetizers generally range from $8 to $14, burgers $13 to $14, pizzas from $9 to $14 and pastas $20 and up. Entrees are $22 to $32.

Seven forty-five on a Saturday night, and the show is about to begin. Regulars file into the corner storefront at Maplewood and Baker, settling into seats that almost seem assigned. There are nods of recognition, glances over to the fellow in charge, a sense of anticipation in not-sohushed exchanges. Corks pop. Wine glasses are filled and the floor crew at Arturo’s switches into high gear. At the rear of the intimate restaurant, chef/maestro Dan Richer already has warmed up his wood-burning oven by firing dozens and dozens of pizzas for the early-eating crowd. But right now, as the 8 o’clock hour approaches, he’s dispatching cups filled with husked cherries, also known as bush cherries. They’re nutty little fruits that look a bit like miniature tomatillos, but taste like nothing else on the planet. Peel back the papery skins, flick the fruit into your mouth and wonder how you’ll ever again eat another sugared peanut or mushy olive as a prelude to dinner. They’re the ideal starter for Richer’s unique show. It’s dinner theater, this ritualistic Saturday night minuet between chef and diner, a paean to all that’s locally grown and produced and catches the chef’s discerning eye. There’s no formal bill of fare on this night, just a procession of plates served forth with no fanfare and minimal explanation. It’s based on the trust Richer has built up between himself and his diners, folks who have warmed to the distinctive style of both the rustic, no-frills dining space and the man who delivers a spare, yet deeply satisfying dining experience. “Coppa, house-made,” is the way our server describes the next dish. He knows no embellishment is needed to sell diners on the veritable kaleidoscope made from cured pork shoulder and its fat, presented as delicate slices of salumi that appear air-brushed on the platter. Alone, or partnered with crusty, country bread, this coppa is pretty darn perfect. Actually, so is Arturo’s. Richer took over the old pizza joint in downtown Maplewood in early 2007 and re-made it to suit his dreams and palate. Pizzas are now of the modern age – that is to say, they go back in time to ovens fueled by wood, to crusts born of kneading and slow-rise techniques, to toppings that tilt toward Spartan, not extra-anything. A welledited selection of those thin-crust pizzas plus pastas are the order of the night five days a week, with Tuesdays turned over to a scaled-back tasting menu and Saturdays the destination-diner extravaganza. On that night, Richer goes strictly market and microseasonal. It’s completely, obsessively ingredient-driven in a good way. Ask about the olive oil, for instance, and you’ll be brought a bottle of the newest member of the Arturo’s Olive Oil Brigade, an unfiltered number from Puglia whose fruitiness makes already silky-sweet scallops even silkier and sweeter. These scallops are the star of Richer’s crudo, a bowl of dense and rich shellfish bathed in the Puglian oil

Seven forty-five on a Saturday night, and the show is about to begin. Regulars file into the corner storefront at Maplewood and Baker, settling into seats that almost seem assigned. There are nods of recognition, glances over to the fellow in charge, a sense of anticipation in not-sohushed exchanges. Corks pop. Wine glasses are filled and the floor crew at Arturo’s switches into high gear. At the rear of the intimate restaurant, chef/maestro Dan Richer already has warmed up his wood-burning oven by firing dozens and dozens of pizzas for the early-eating crowd. But right now, as the 8 o’clock hour approaches, he’s dispatching cups filled with husked cherries, also known as bush cherries. They’re nutty little fruits that look a bit like miniature tomatillos, but taste like nothing else on the planet. Peel back the papery skins, flick the fruit into your mouth and wonder how you’ll ever again eat another sugared peanut or mushy olive as a prelude to dinner. They’re the ideal starter for Richer’s unique show. It’s dinner theater, this ritualistic Saturday night minuet between chef and diner, a paean to all that’s locally grown and produced and catches the chef’s discerning eye. There’s no formal bill of fare on this night, just a procession of plates served forth with no fanfare and minimal explanation. It’s based on the trust Richer has built up between himself and his diners, folks who have warmed to the distinctive style of both the rustic, no-frills dining space and the man who delivers a spare, yet deeply satisfying dining experience. “Coppa, house-made,” is the way our server describes the next dish. He knows no embellishment is needed to sell diners on the veritable kaleidoscope made from cured pork shoulder and its fat, presented as delicate slices of salumi that appear air-brushed on the platter. Alone, or partnered with crusty, country bread, this coppa is pretty darn perfect. Actually, so is Arturo’s. Richer took over the old pizza joint in downtown Maplewood in early 2007 and re-made it to suit his dreams and palate. Pizzas are now of the modern age – that is to say, they go back in time to ovens fueled by wood, to crusts born of kneading and slow-rise techniques, to toppings that tilt toward Spartan, not extra-anything. A welledited selection of those thin-crust pizzas plus pastas are the order of the night five days a week, with Tuesdays turned over to a scaled-back tasting menu and Saturdays the destination-diner extravaganza. On that night, Richer goes strictly market and microseasonal. It’s completely, obsessively ingredient-driven in a good way. Ask about the olive oil, for instance, and you’ll be brought a bottle of the newest member of the Arturo’s Olive Oil Brigade, an unfiltered number from Puglia whose fruitiness makes already silky-sweet scallops even silkier and sweeter. These scallops are the star of Richer’s crudo, a bowl of dense and rich shellfish bathed in the Puglian oil  with needle-thin slivers of French breakfast radish that add color and bite to the raw-fish dish. There are a few twirls of baby greens—so tiny that they probably are better thought of as newborn greens—to add color and contrast, and that’s it. It’s gentle, it’s refined, it’s an exacting example of what this chef is trying to do: simplify, simplify, simplify. That’s his culinary style, and it’s both brave and smart. While others less secure in their métier, less confident of their skills, fuss and add a silly number of frills to a plate, Richer practices the art of the take-away. He pares down a dish to its fundamentals, letting his ingredients assume center stage. A salad of baby arugula, for instance, is accented by thin slices of peaches and flecks of shaved Parmigiano- Reggiano. That’s it. High-season tomatoes, both cheery Sun Golds and beefy San Marzanos, are chopped and set in a glass compote to be served only with a sprinkling of sea salt. The tomatoes’ own juices make it good to the last drop. Tagliolini, a thin-strand pasta, is too fresh, too creamy in taste and texture to need anything more than a handful of teeny cubes of zucchini and a little grated Parmigiano Reggiano. We all but bribed our server to admit to an infusion of cream or butter. No, we were told. Nothing but the fresh pasta, the zucchini, the Parmigiano-Reggiano. That’s what good pasta can do. And a good hunk of pork shank needs but a bed of earthy kale to keep it company. In northern states, it’s such an underappreciated partnership, anything pig and greens. In Richer’s hands, it could be the next big thing in Yankeeland. His whipped ricotta, served with raspberries and what possibly was a mirage of shaved dark chocolate, is precisely what dessert should be: neither overwhelmingly sweet nor baroque in scale. I would’ve had seconds had seconds been offered, however, since I’ve always dreamed of cheese and fruit being transformed into just this kind of finale. I left Arturo’s thinking that either I should 1) move to Maplewood or 2) convince Richer to take his show on the road to my hometown. I’ll further assess these options when I return to Arturo’s for the duck prosciutto, hazelnut-pear salad and pasta with wild boar ragu. For without a doubt, this food needs to be a regular part of my eating life. EDGE

with needle-thin slivers of French breakfast radish that add color and bite to the raw-fish dish. There are a few twirls of baby greens—so tiny that they probably are better thought of as newborn greens—to add color and contrast, and that’s it. It’s gentle, it’s refined, it’s an exacting example of what this chef is trying to do: simplify, simplify, simplify. That’s his culinary style, and it’s both brave and smart. While others less secure in their métier, less confident of their skills, fuss and add a silly number of frills to a plate, Richer practices the art of the take-away. He pares down a dish to its fundamentals, letting his ingredients assume center stage. A salad of baby arugula, for instance, is accented by thin slices of peaches and flecks of shaved Parmigiano- Reggiano. That’s it. High-season tomatoes, both cheery Sun Golds and beefy San Marzanos, are chopped and set in a glass compote to be served only with a sprinkling of sea salt. The tomatoes’ own juices make it good to the last drop. Tagliolini, a thin-strand pasta, is too fresh, too creamy in taste and texture to need anything more than a handful of teeny cubes of zucchini and a little grated Parmigiano Reggiano. We all but bribed our server to admit to an infusion of cream or butter. No, we were told. Nothing but the fresh pasta, the zucchini, the Parmigiano-Reggiano. That’s what good pasta can do. And a good hunk of pork shank needs but a bed of earthy kale to keep it company. In northern states, it’s such an underappreciated partnership, anything pig and greens. In Richer’s hands, it could be the next big thing in Yankeeland. His whipped ricotta, served with raspberries and what possibly was a mirage of shaved dark chocolate, is precisely what dessert should be: neither overwhelmingly sweet nor baroque in scale. I would’ve had seconds had seconds been offered, however, since I’ve always dreamed of cheese and fruit being transformed into just this kind of finale. I left Arturo’s thinking that either I should 1) move to Maplewood or 2) convince Richer to take his show on the road to my hometown. I’ll further assess these options when I return to Arturo’s for the duck prosciutto, hazelnut-pear salad and pasta with wild boar ragu. For without a doubt, this food needs to be a regular part of my eating life. EDGE

“}e21`perch in the L-shaped first-floor dining room, a table for 10 catty-corner from ours is being readied for guests. Before long, on our other side, a few tables are being pushed together by the busy floor crew. I ask a server how many will be in that party. He shrugs and says, “Either 10 or 12. We’ll find out when they get here.” Party Central in Kenilworth. Boulevard Five72 is fit for celebrations and, on this weekend night, folks everywhere are toasting one another. Servers sashay around the dining spaces briskly and purposefully as the evening promises to crescendo every 15 minutes. Everyone and everything is dressed for the occasion. Approach the restaurant, which sits stately on the main thoroughfare that lends its name to Boulevard Five72, and you might think it looks something like a French chateau. Inside, there’s a bit of a French provincial feel to the décor, dominated by shades of beige and wood tones. It’s an appropriately restful backdrop to the constant-motion dining scene. Snag a bottle of wine from the list and settle in. Chef-partner Scott Snyder’s menu is amenable to almost anything you might be in the mood for. I’d suggest going for one of the value-priced red wines from Spain and letting it do-si-do with the fava bean ravioli nestled in a rustic rabbit ragout. It’s the standout dish on the menu of the moment at Boulevard Five72—a partnership of stalwarts from the south of France that have long earned their stripes at the table. Snyder finishes the starter with an ethereal pouf of truffle scented mascarpone that provides yet another flavor bridge from rabbit to fava to pasta. Or you might consider the crab cake, which here comes accompanied by a coarse chop of a salsa, starring chickpeas

“}e21`perch in the L-shaped first-floor dining room, a table for 10 catty-corner from ours is being readied for guests. Before long, on our other side, a few tables are being pushed together by the busy floor crew. I ask a server how many will be in that party. He shrugs and says, “Either 10 or 12. We’ll find out when they get here.” Party Central in Kenilworth. Boulevard Five72 is fit for celebrations and, on this weekend night, folks everywhere are toasting one another. Servers sashay around the dining spaces briskly and purposefully as the evening promises to crescendo every 15 minutes. Everyone and everything is dressed for the occasion. Approach the restaurant, which sits stately on the main thoroughfare that lends its name to Boulevard Five72, and you might think it looks something like a French chateau. Inside, there’s a bit of a French provincial feel to the décor, dominated by shades of beige and wood tones. It’s an appropriately restful backdrop to the constant-motion dining scene. Snag a bottle of wine from the list and settle in. Chef-partner Scott Snyder’s menu is amenable to almost anything you might be in the mood for. I’d suggest going for one of the value-priced red wines from Spain and letting it do-si-do with the fava bean ravioli nestled in a rustic rabbit ragout. It’s the standout dish on the menu of the moment at Boulevard Five72—a partnership of stalwarts from the south of France that have long earned their stripes at the table. Snyder finishes the starter with an ethereal pouf of truffle scented mascarpone that provides yet another flavor bridge from rabbit to fava to pasta. Or you might consider the crab cake, which here comes accompanied by a coarse chop of a salsa, starring chickpeas  with a cameo of fruit. The punchline of the appetizer? A flash of sriracha sauce, moderated by avocado. As I ate, I thought there’d be nothing wrong with giving that hot-fun sriracha more of a chance to dance around the plate: Between the sweetness of the crab and the earthiness of the chickpeas, the dish has the foundation to stand up to more heat. Go for it. Shrimp punctuate a chunky corn chowder that benefits from a trio of compelling accents: smoky bacon, celery root and a touch of turnip. It’s a solid soup—one worth exploring all summer long—as Snyder and his kitchen crew riff on the shellfish and switch around the accenting vegetables to stay in season. One vegetable I wish they’d switch out is the red flannel hash that’s made from

with a cameo of fruit. The punchline of the appetizer? A flash of sriracha sauce, moderated by avocado. As I ate, I thought there’d be nothing wrong with giving that hot-fun sriracha more of a chance to dance around the plate: Between the sweetness of the crab and the earthiness of the chickpeas, the dish has the foundation to stand up to more heat. Go for it. Shrimp punctuate a chunky corn chowder that benefits from a trio of compelling accents: smoky bacon, celery root and a touch of turnip. It’s a solid soup—one worth exploring all summer long—as Snyder and his kitchen crew riff on the shellfish and switch around the accenting vegetables to stay in season. One vegetable I wish they’d switch out is the red flannel hash that’s made from  beets and plated with the grilled salmon. The grainy mustard and pesto-like spinach purée adds spot-on counterpoints to the moist fish, but the root vegetable clashes with the salmon. A basic strip loin, meanwhile, showed the kitchen’s precision, and the rich reduction of red wine swirled on the plate was all the steak needed. But a haystack of onions that looked more frizzled than frittered, as the menu described, proved an amiable companion, so we gobbled it all up. Why not? Steak and onions are a heavenly marriage. As are shellfish and arborio, the basis for Boulevard Five72’s risotto. It’s heavy on the truffle in its lobster broth, which I know draws applause from a multitude of

beets and plated with the grilled salmon. The grainy mustard and pesto-like spinach purée adds spot-on counterpoints to the moist fish, but the root vegetable clashes with the salmon. A basic strip loin, meanwhile, showed the kitchen’s precision, and the rich reduction of red wine swirled on the plate was all the steak needed. But a haystack of onions that looked more frizzled than frittered, as the menu described, proved an amiable companion, so we gobbled it all up. Why not? Steak and onions are a heavenly marriage. As are shellfish and arborio, the basis for Boulevard Five72’s risotto. It’s heavy on the truffle in its lobster broth, which I know draws applause from a multitude of  diners impressed by the presence of extreme luxury. I’m a little less drawn to the use of truffle oil than most; I think it overwhelms shellfish, in particular, keeping its unique character in the closet. We added character to our entrées in the form of two sides well worth the supplement. Spanish chips are one of the planet’s most enjoyable foods. Here the thick-cut potato slices are crisp and crunchy and judiciously dusted with pimenton and salt. Good greens are spiced just right—and right for just about any of Boulevard Five72’s entrées. My suggestion re the greens? Serve with a wedge of lemon to give diners the option of adding a little zing as desired. There’s citrus aplenty in the steamed pudding cake, an elegant finale served with a side of blackberry sorbet. An updated strawberry shortcake was underscored by a faint drop of balsamic vinegar and partnered with a creamy, subtle basil gelato. A favorite at my table was the dark chocolate-caramel tart, with its delightful sprinkling of fleur de sel and a cloud of mascarpone mousse offered as a finishing flourish. As we wound down our dinner, servers were gearing up for yet another large-party table. Amid all the activity, you might notice a slight slow-down between appetizers and main courses, and maybe your entrée plates are left to sit a tad too long after you’ve set down knife and fork. But the crew, largely, performs admirably. The crescendos continue at Boulevard Five72. EDGE

diners impressed by the presence of extreme luxury. I’m a little less drawn to the use of truffle oil than most; I think it overwhelms shellfish, in particular, keeping its unique character in the closet. We added character to our entrées in the form of two sides well worth the supplement. Spanish chips are one of the planet’s most enjoyable foods. Here the thick-cut potato slices are crisp and crunchy and judiciously dusted with pimenton and salt. Good greens are spiced just right—and right for just about any of Boulevard Five72’s entrées. My suggestion re the greens? Serve with a wedge of lemon to give diners the option of adding a little zing as desired. There’s citrus aplenty in the steamed pudding cake, an elegant finale served with a side of blackberry sorbet. An updated strawberry shortcake was underscored by a faint drop of balsamic vinegar and partnered with a creamy, subtle basil gelato. A favorite at my table was the dark chocolate-caramel tart, with its delightful sprinkling of fleur de sel and a cloud of mascarpone mousse offered as a finishing flourish. As we wound down our dinner, servers were gearing up for yet another large-party table. Amid all the activity, you might notice a slight slow-down between appetizers and main courses, and maybe your entrée plates are left to sit a tad too long after you’ve set down knife and fork. But the crew, largely, performs admirably. The crescendos continue at Boulevard Five72. EDGE