- 900 South Ave. West Westfield NJ 07090

- 973-377-MATH (6284)

- visit website

- 2299 Vauxhall Rd. Union NJ 07083

- 908-964-7800

- visit website

- 42 Norwood Ave. Summit NJ 07902

- 908-273-0900

- visit website

- 1000 Morris Ave. Union NJ 07083

- (908)737-5326

- visit website

- 1000 Morris Ave. Union NJ 07083

- (908)73-READY (73239)

- visit website

- 1969 Morris Ave. Union NJ 07083

- 908-851-7711

- visit website

- 25 Saint Bernards Rd. Gladstone NJ 07934

- (908)234-1611

- visit website

- 52 Great Hills Rd. Short Hills NJ 07078

- (973)379-3442

- visit website

- 230 Mendham Rd. Morristown NJ 07960

- (973)538-3231, Ext. 3019

- visit website

- 700 Shunpike Rd. Chatham NJ 07928

- (973)410-0400

- visit website

- 840 N. Broad St. Elizabeth NJ 07208

- (908)352-0670

- visit website

- 99 South St. New Providence NJ 07074

- (908)464-8652

- visit website

Five challenges facing New Jersey education

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Most school administrators wouldn’t trade their job for anyone else’s. That being said, most wouldn’t wish their job on their worst enemy. Whether calling the shots in a public, private, faith-based or boarding school, the people who run New Jersey’s halls of education are engaged in a never-ending game of Whack-A-Mole: As soon as one problem is addressed, two more always seem to pop up. None of these problems, it is worth noting, is simple. Nor is much in the way of extra help available to deal with them. In fact, since the 1980s, the number of teachers in New Jersey has grown by nearly a third. The number of administrators during that time has gone up a mere two percent. New Jersey’s public schools handle about 1.4 million kids in a given year, and their budgets make up the largest state-funded operation.

Our students rank high nationally in reading, writing and arithmetic, and we have the best high-school graduation rate in the country. New Jersey’s private schools rank among the best in the nation, too. Even so, our schools—all of our schools—have had to face significant challenges in the early part of the 21st century. Some are obvious, like budgeting. Everyone could use more money, from language arts instructors to librarians to lunch ladies. At the same time, budget reformers are looking for creative ways to slash school budgets, which in some places are driving property taxes up so high that many residents can’t afford to stay in the towns they’ve lived in for generations. In these pages, we’ll veer off the beaten path a bit and look at five topics that you either don’t hear much about, or don’t think about too much when you do hear about them. All are on the daily schedule for school administrators, and present some of their most difficult challenges.

TEACHER PERFORMANCE This is an incredibly complex issue. Who are the best teachers? Are they the ones who consistently turn out superb test-takers? Are they the ones whose students come back to visit 10 and 20 years later? Are they the ones who take thankless jobs in the most troubled school systems? These questions are not only relevant from a quality-of-education standpoint. With more and more discussion about the creation of incentives for great teachers—and a mechanism for getting rid of some lousy ones—there will be a need for some quantifiable measurements. And those measurements will have to include metrics that take into account the challenges each educator faces in his or her classroom. That is why all eyes are focused on the Newark school system, which famously received a pile of Facebook stock from Mark Zuckerberg three years ago.

In the new contract negotiated with city teachers at the end of 2012, there is a provision for merit pay. Teachers rated as “highly effective” can now pocket $5,000 in bonus money, which comes right out of the Facebook fund. Teachers in the more troubled schools can earn even more, as can math and science teachers. Teachers rated as “effective” will receive an agreed-upon pay raise every year they maintain that standing. Newark’s teachers are represented by the American Federation of Teachers, which negotiated the bonus terms. Most public educators in the state are represented by the New Jersey Education Association, which to this point has stood firmly against a bonus scheme. Needless to say, the NJEA will come under pressure to consider teacher bonuses if the Newark experiment is a success. What does success look like? More money for outstanding teachers, a fair wage for competent ones, and perhaps a way to ease out chronic under-performers.

SECURITY In the wake of the New-town tragedy, every school in the state had to reexamine its readiness and vulnerability in emergency situations. The process was expensive, time-consuming and eye-opening. For a while, everyone was nattering about armed guards in the hallways and even armed teachers in the classrooms. It appears that cooler heads have prevailed. The fact of the matter is that armed intruders are incredibly rare; a far more likely emergency scenario is an out-of-control parent, power failure or dangerous weather event. The bad news is that most New Jersey schools lack adequate staff training on the procedures needed to deal with these emergencies. There is actually an Office of School Preparedness and Emergency Planning. As you might imagine, its inspectors have been very busy since the Sandy Hook shootings. Some of their visits are scheduled, while others are unannounced. The goal is not to “catch” public schools unprepared, but to make sure that they follow a set protocol for lock-downs and other safety drills. The state has always had relatively strict drill requirements, so it has been more of a fine-tuning process than an overhaul.

Private schools are a different matter. They tend to operate more openly to project a warm and welcoming feeling to current and prospective parents. Many of these schools have drop-off and pick-up “traditions” that they are reluctant to change, even when they might compromise security. In some schools, parents could slap a Visitor sticker on and roam the halls without attracting a second look. Well, this situation has changed dramatically in the last year. Parents who were once charmed by a feeling of openness have started looking at their schools with a more critical eye. As a result, most private schools—at considerable expense—have undergone security audits, and are now making substantial changes to their physical spaces, technology, and visitor policies. These changes have to be paid for. In some cases, schools will dip into their endowments. In others, there will be a noticeable bump in tuition.

HOMEWORK The point of homework is not just to educate students outside the classroom. It helps them develop time-management skills and teaches them lessons in accountability they will need to learn before moving on to college or into the workforce. The challenge public schools face is that students who will not (or cannot) complete their homework assignments fall behind the rest of the class. They become disinterested or disenchanted or disruptive. Over the course of a semester, depending on the school system, a teacher who is tough about homework is likely to find a large portion of the class far behind by the time final grades are given. In subjects where testing is used to measure a school’s success (and by extension, a teacher’s effectiveness), everyone loses. So what’s a teacher to do? In many instances, a large portion of class time is now devoted to getting homework done!

This is the only way to ensure that every student is on the same page. Unfortunately, this limits the amount of material that can be covered in class. It is also creating a generation of kids with a lot of un-monitored after-school time to kill, which isn’t necessarily a good thing. The challenge for private schools where homework is concerned often comes down to blow-back from parents about too much. Above 5th or 6th grades, most private schools have a policy limiting homework to no more than 15 to 30 minutes per subject. Of course, if three classes give a half-hour each, a project is due in a fourth class, and a student needs to study for a quiz or exam in a fifth class, the result can be a meltdown. And guess who deals with that? The parents…who are paying thousands of dollars a year (sometimes tens of thousands) in tuition. Many feel that this buys them the privilege of not having to crack the whip on homework assignments.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

RECESS (aka GYM) Recess—or free time for physical activities—has long been a tradition in both public and private education. Researchers agree that its value includes the development of cognitive skills outside the classroom environment, including cooperation, teamwork and communication. Recess has also been shown to have a direct link to improved academic performance. And, of course, activity during the school day is one way of addressing the obesity issue. The problem is that the number of schools with a structured PE curriculum is shrinking—in some cases for budgetary or manpower reasons, in others because of liability concerns.

In schools that need to improve their measurable academic success, outdoor time has actually been cancelled to give students extra time to prep for tests. Those schools that continue to schedule recess or gym classes have in many cases devolved into little more than active socializing. Indeed, at some schools, “walking and talking” constitutes an adequate amount of physical activity. A recent study estimated that two in five schools have either eliminated recess or reduced it. In lower-income districts, the cuts have been even more dramatic. The situation has become so distressing that, this past year, Shirley Turner, a state senator representing portions of Mercer and Hunterdon Counties, introduced a bill requiring public schools to provide a daily recess period, but only through fifth grade.

BULLYING In the last five years, national attention has been focused on the issue of bullying in schools. It is on the rise nationwide, and in New Jersey, too. The rapid growth of social media has certainly added fuel to what was a smoldering fire. So, too, has the focus on confrontation in the reality shows that young people watch. Schools have combated this growing problem as best they can, including a stronger anti-bullying law that went into effect in New Jersey during the 2011–12 school year. That law compelled schools to designate an Anti-Bullying Coordinator, who must report every incident. Prior to the 2011 legislation, reports of school bullying had risen sharply, by 15 to 20%, over a three-year period, according to the state’s Department of Education. Critics of the new rule claimed that the stricter reporting requirement might send the bullying numbers soaring.

However, this doesn’t appear to be the case. In some districts, bullying incidents actually fell. In others they remained fairly consistent. In a few, they spiked. Who are the bullies? About a third of reported incidents involve seventh- and eighth-graders. A quarter occur among ninth- and tenth-graders. Fewer than 1 in 20 of these incidents was linked to racial or religious bias, so basically it’s kids being jerks. Some have posited that the rise in bullying may be linked to the punishment now meted out in public schools for physical violence. In the old days, standing up to a bully meant punching him in the mouth—or at least making yourself a hard target. Now that response would carry an automatic suspension. Others point out that if a bully is using social media as a weapon, a punch in the mouth isn’t even an option anymore. The notion that bullying is less of a problem in private schools may be accurate, but it is not supported by any hard numbers. Those institutions are not compelled to report bullying, and each sets its own policy. To be certain, bullying does occur in New Jersey’s private, faith-based and boarding schools. It may be more subtle or sophisticated, and some cases may involve influential families, so administrators must tread lightly before dropping the hammer on a bully.

Editor’s Note: What might this same article include a year from now? Some trends to keep an eye on are New Jersey’s adoption of national Common Core standards. New York adopted them recently and saw its test scores fall. It will also be interesting to watch the development of Governor Christie’s Regional Achievement Centers, which are meant to be a resource for teachers and parents, but thus far have been underutilized. And finally, a debate may be on the horizon regarding the skyrocketing costs of special education.

Of note to teachers and parents: TRMC’s Department of Behavioral Health & Psychiatry produced Step-Up, Take Action: When Does a Child Need Help? Log onto edgemagonline.com for a free PDF version in English or Spanish.

Abraham Browning Photo courtesy of NJ.gov

Why do our license plates say Garden State? Unless you are in law enforcement, it is doubtful that you spend a lot of time thinking about license plates. However, if you are 60 or younger, that slogan has probably been attached to every car you or your family has ever owned. At the time Garden State was added to our license plates in 1955, the term had been in use as an unofficial nickname for well over half a century. The characterization of New Jersey as a garden may not seem right to out-of-towners, but anyone who has spent any time here knows how incredibly productive the soil is in all but a couple of places. In the 1700s and 1800s, New Jersey served as the primary food source for two of the nation’s fastest-growing cities, New York and Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin likened our state to a barrel of food, open at both ends, nourishing two major populations.

Legend has it that the term Garden State came into wide use after the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. During that event, Abraham Browning, New Jersey’s Attorney General in the years prior to the Civil War, gave a speech in which he described his home state as “an immense barrel filled with good things to eat and open at both ends—with Pennsylvanians grabbing from one end and the New Yorkers from the other.” It was during this speech that he supposedly dubbed New Jersey the Garden State. When the license plate bill was introduced in Trenton in 1954, Governor Robert Meyner decided to investigate the origin of the slogan and determined that at no time had it ever been recognized officially. Focused on promoting the state’s growing reputation as a business-friendly industrial player, Governor Meyner felt the word garden sounded too rural—and actually vetoed the bill! “I do not believe that the average citizen of New Jersey regards his state as more peculiarly identifiable with gardening for farming than any of its other industries or occupations,” he said. The legislature ignored him, overrode the veto, and early the next year the new license plates started arriving at Motor Vehicles.

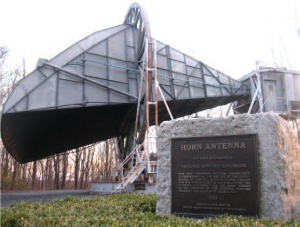

Photo courtesy of Fabioj

Who came up with the Big Bang theory? If you were hoping to read about Leonard, Sheldon, Howard and Raj, skip to the next teachable moment. This Big Bang happened billions of years ago—and was “discovered” by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson in 1965. The two radioastronomers, working at Bell Labs in Holmdel, were interested in measuring radio signals coming from space. They were given permission to use a satellite receiver (from an obsolete project called Echo), which was destined for the scrapheap. It just happened to be perfect for their experiments. As soon as Penzias and Wilson began, they noticed a static-y background signal in the microwave range.

Until they eliminated this mysterious noise, they could not continue with their work. The problem was complicated by the fact that, no matter where they pointed the receiver, they heard the same noise. They began ruling out various possibilities. It was not an extra-terrestrial radio signal. It had nothing to do with nearby New York City. An above-ground nuclear test was not the culprit either. It occurred to the scientists that perhaps the pigeons living in the antenna were creating the problem. They shooed them away and then swept out their poop themselves. Next, they turned to the work of others. In 1929, Edwin Hubble had shown that the galaxies we could see from earth seemed to be moving away from us. This suggested that the universe had been compacted at some point.

In England, astrophysicist Stephen Hawking and two colleagues were taking Albert Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity and trying to work backwards to measure time and space. The conclusion they drew was that time and space had a “beginning”—and that all matter and energy originated at that point. Closer by, in Princeton, Robert Dicke theorized that if such an origination point existed, then the residue of the “big bang” that created the universe would be evident in consistent, low-level background radiation anywhere you looked. What Dicke needed was evidence. After four frustrating seasons, Penzias and Wilson began reaching out to their colleagues. They contacted Dicke and presented their dilemma. Of course, he knew exactly what the noise was. Dicke shared his theoretical work, knowing he’d been “scooped.” The three scientists published their findings and in 1978, Penzias and Wilson received the Nobel Prize. One wonders if they could have imagined this outcome more than a decade earlier, while they were sweeping bird droppings off their receiver.

How did our bridges and tunnels get built? New Jerseyans don’t like it a bit when Manhattanites deride them as the “Bridge & Tunnel” crowd. But bridges and tunnels provide vital lifelines for urban dwellers and, lest we forget, they do not build themselves. In the case of the Holland Tunnel to New York and the Ben Franklin Bridge to Philadelphia, credit goes to the vision, political will and—surprise!—unbridled corruption of two of the state’s iconic influence-peddlers: Frank Hague and Enoch “Nucky” Johnson. Hague clawed his way to power in Hudson County beginning in the 1890s, rising from the job of Jersey City constable to ward boss to City Commissioner by 1913. During World War I, Hague filled a power vacuum and seized control of the state’s most populous and richest county.

He was elected Jersey City Mayor in 1917. Johnson, the inspiration for Nucky Thompson in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, held a number of different official positions in Atlantic City. He ascended to role of political boss in 1911 after his predecessor was jailed. He quickly consolidated this position and held it for three decades. To stimulate business for his town, Johnson made sure that city officials looked the other way when it came to enforcing laws against gambling, prostitution and liquor. When Prohibition kicked in a few years later, Atlantic City became a Mecca of vice and Johnson’s take on this illicit business was hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Between the two machine bosses, they controlled enough money and manpower in New Jersey to get almost anything done— or make almost anyone disappear. They first joined forces in 1916. Johnson was the campaign manager for Walter Evans Edge, a state senator from Atlantic County who had his eye on the White House.

The first step was to get him to the governor’s mansion. This would be tricky, as Edge was a Republican and Hague was a Democrat who controlled votes in the northern half of the state. Johnson (then 33) met with Hague (then 40) and suggested they forge a partnership that would serve both their ambitions going forward. Hague instructed his organizers to make sure Edge won the Republican primary, and then yanked his support from a stunned Democratic candidate Otto Wittpenn in the general election. With Edge running things in Trenton, Johnson’s power grew. The new governor rewarded him by making him Clerk of the State Supreme Court. He also pushed through laws that gave New Jersey’s cities more autonomy, which helped solidify Johnson and Hague as machine bosses. In 1917, Governor Edge “rewarded” Johnson and Hague by reorganizing the state highway department. This enabled him to authorize the construction of a bridge between South Jersey and Philadelphia (the Ben Franklin Bridge) and a tunnel between Jersey City and Manhattan (the Holland Tunnel).

The bridge opened in 1926 and the tunnel opened in 1927. Both projects transformed the cities that Johnson and Hague controlled. After 30 years, the law finally caught up with Johnson. For years, he had listed enormous amounts of income from gambling, prostitution and kickbacks on his tax return as “other contributions.” The IRS finally nailed him in 1941. Hague fared better during FDR’s administration. Indeed, the lion’s share of federal funds earmarked for New Jersey was put under Hague’s control, conspicuously bypassing the state’s senators or governors. Hague finally resigned as Jersey City Mayor when the new state constitution went in place in 1947.

It was rewritten largely to curtail the influence of local political bosses, and he knew it. Edge went on to enjoy a long and productive national and state political career, but never made it to the White House. He was the fron-trunner for vice president on Warren Harding’s ticket in 1920, but enemies he made with his wheeling and dealing in the Garden State blocked his candidacy, and Calvin Coolidge ended up as Harding’s running mate. Coolidge ascended to the presidency after Harding died in office. Who knows what New Jersey would look like today had Edge been president instead of Coolidge. One can only imagine the extent to which Frank and Nucky might have elevated their power.

Photo Courtesy of Twin Lights Historical Society

Where was the Pledge of Allegiance given for the first time? The Pledge of Allegiance was first published on September 8, 1892, in The Youth’s Companion, a children’s magazine that enjoyed wide circulation across the United States. On April 25, 1893, the Pledge was given for the first time as America’s official national oath of loyalty in a ceremony atop the Navesink Highlands, overlooking Sandy Hook. How the Pledge made this extraordinary journey in less than eight months is a story that is still not covered in most textbooks. The Pledge originated in the offices of The Youth’s Companion in Boston as part of a promotion to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering America.

The publisher’s nephew, James Upham, was in charge of marketing the publication. His goal was to sell flags through advertising that appeared on the magazine’s back pages. Knowing that schools did not typically have flags in their classrooms, he came up with the clever idea of having students recite a pledge of loyalty to the flag at the start of each school day. At a time when patriotism in America was on the rise, this seemed like a sure bet. The writer of the pledge was Francis Bellamy, a local Baptist minister and occasional contributor to the Companion. He may or may not have had editing help, but the final result was I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. An ardent socialist, Bellamy had originally include the words equality and fraternity in the Pledge. It was decided that no one quite knew what fraternity meant (it was an expression held over from the French Revolution), and that equality might offend those who frowned upon the notion than women and African Americans might share in the advantages enjoyed by white males.

The Pledge of Allegiance immediately caught the attention of President Benjamin Harrison, who was running for reelection that fall. Harrison proclaimed that October 12 would now be Columbus Day, and ordered that the Pledge be recited in schools on that morning. It soon became a daily practice in many schools, and at various public events. Harrison ended up losing the election to Grover Cleveland (the nation’s only NJ-born president), but Cleveland continued to carry the ball on the Pledge. As the April 1893 opening of the Colombian Exposition in Chicago approached (it was a year late because of construction delays), it became clear to Cleveland and others in his administration that a “mirror event” somewhere on the East Coast would be necessary. A Newark businessman named William McDowell entered the picture at this time. On his various return trips from Europe via steamship, McDowell noted that the greatest commotion on board was not when the incoming immigrants passed that new statue, Liberty Enlightening the World, but upon the first sighting of the coastline. The first piece of America immigrants saw rising over the horizon on their way into New York Harbor was the Navesink Light Station, better know as the Twin Lights. McDowell believed there should be a flag atop the highlands, between the two lights, that was double their height.

Having already secured funds to erect this 135- foot Liberty Pole, he joined forces with The Youth’s Companion and government officials to hold a ceremony to make the Pledge of Allegiance “official” at the same time the Chicago World’s Fair was opening. On April 25th, several hundred local and national dignitaries gathered on a hastily constructed grandstand to witness the dedication of the Liberty Pole at the Twin Lights. It was a miserable, drizzly morning punctuated by several speeches and flag raisings. The Pledge of Allegiance was given for the first time as the official oath of loyalty. A flotilla of international warships fired salutes as it made its way north toward Sandy Hook. The following day, the ships were assembled for a naval review in New York Harbor, followed by parades and a couple of days of social events. Because Cleveland chose to bypass the flag-raising (he managed to make the parties in New York) and because almost every reporter of note in America was in Chicago to cover the Colombian Exposition, the day the Pledge became official never made it into the history books. The wording has changed a couple of times in the last 120 years, and the way we salute the flag has, too. One thing, however, remains the same—the Pledge of Allegiance is the symbolic final threshold every new American must cross before he or she becomes a U.S. citizen.

Who’s hiring our college grads?

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Putting a child through college is a stressful, frustrating, financially draining experience. Parents able and willing to do so deserve a medal. What do they receive? According to a poll by the research firm Twenty-something, Inc., 85 percent get their kids back. Of all the economic numbers confronting moms and dads these days, that one may just be the most deflating. In many cases, the newly minted grad comes home to roost until his or her employment picture gains some clarity.

Though the economic climate may have improved since the worst of times in 2008 and 2009—which marked a loss of more than eight million jobs nationwide—college graduates and displaced job seekers continue to face a less-than-welcoming marketplace in the Garden State. A recent survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) indicated that just about 25 percent of 2012 diploma recipients had jobs waiting for them upon graduation. “While this number represents a slight increase from recent years, it’s still far from healthy,” says Greg Mass, Executive Director of Career Development Services at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) in Newark. An even more disconcerting reality for recent grads: this past summer, New Jersey’s unemployment rate climbed to nearly 10 percent, the highest it has been since 1977.

Fortunately, it’s not all bad news. Representatives of the state’s colleges and universities say it isn’t necessarily that jobs are unavailable in New Jersey, it’s that job seekers simply need to know where—and how—to find them. They point to emerging trends that shed some light on which industries may be bouncing back better than others. Not surprisingly, students who are proficient in the latest technologies will find the biggest pool of potential jobs across the state—and they know it. This year, Computer Science, Information Technology, Engineering, and Information Systems were among the most sought after disciplines, Mass says.

SOCIAL MEDIA BOOM Any parent concerned that their college-aged child spends too much time on Facebook might breathe a little easier knowing that this shift in the way people communicate has actually led to a slew of career opportunities in social media. According to Ryan Stalgaitis, Career Counselor and Internship Coordinator at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, companies are actively recruiting employees who have the know-how to manage their presence on platforms like YouTube and Twitter. “The number-one industry for jobs in New Jersey is anything that deals with social media,” he says, noting that the university is responding to the demand with courses that allow Communications students to pursue a concentration in social media. Likewise, the university’s marketing programs are also experiencing an uptick in enrollment, he adds. “No matter what industry they’re in, all businesses have a need for an online presence today,” says Reesa Greenwald, Interim Director of the Career Center at Seton Hall University in South Orange. “And they need new employees who will be able to help create a stronger Facebook presence, or to properly manage a LinkedIn account,” It’s also an area where recent grads have a leg up on displaced job seekers who have been out of college for a decade or more, she notes.

Even so, students still need to possess traditional communication skills. “We’re still hearing from employers that students need to have stronger writing and interpersonal skills,” says Dr. Joyce Strawser, Dean of the Stillman School of Business at Seton Hall University. The state’s institutions of higher education are trying to stay ahead of the curve in their quest to prepare students for the new demands of the workforce. “Colleges have been responding to developments in technology and business by creating majors that hardly existed five or 10 years ago,” Mass explains. Indeed, many colleges are ramping up their new media offerings to prepare students for careers in cutting-edge industries like game design, animation and programming, graphic design, and e-text and web publication.

9/11 KIDS New Jersey’s college students literally grew up in the “shadow” of 9/11. It changed their world view as kids, and now it’s starting to change their post-graduate careers in interesting ways. Many are finding employment daylight in security-based careers such as information assurance, cybersecurity and homeland security. Others feel compelled to give back to local communities by seeking employment in the non-profit sector. “When we look at the entire spectrum of employment over the past four graduating classes, we see that nonprofit consistently emerges as the top industry of choice for our graduates,” says Beverly Hamilton-Chandler, Director of Career Services for Princeton University. There are some careers that have continued to remain in demand in New Jersey for decades.

Accounting remains on top of the list of fields actively recruiting new employees; positions in the healthcare industry have remained steady even throughout the worst of the recession. According to Kim Crabbe, Director of the Center for Career Development at Drew University, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and biotech firms remain among the top sources for jobs in the state. Yet even in a field like healthcare, where jobs are relatively plentiful, many potential employees are finding that flexibility is key when it comes to channeling their skills and education into a career. “They may have earned a major in a particular field, but students need to know there are lots of things they can do with their skill set,” points out Carolyn Jones, Executive Director of the Center for Career Services and Cooperative Education at Montclair State University. “One of our goals is to help students understand that not everyone in the pharmaceutical industry wears a lab coat.” “Job seekers have to be open to pursuing opportunities that may not be their dream career, but that will at least get their foot in the door,” Stalgaitis adds.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

DOG EAT DOG EAT DOG In many cases, it’s not the career path students choose to pursue, but the steps they’re taking to land coveted full-time positions. Today’s graduates are finding that some tried-and-true methods of job searching—like mailing out résumés and waiting for a response—may no longer pan out. Networking both in-person and online remains the most successful method. “Students have to be assertive,” Strawser advises. “They have to be hungry for that job. They have to learn to follow up, and know how to take networking to the next level.” Not only are New Jersey grads competing with one another for full-time work, they’re also finding themselves up against older workers (who are more credentialed and experienced) due to layoffs, as well as graduates from the last several years, who are still seeking gainful employment.

Some students are even opting to leave the Garden State in search of that first full-time gig. “Graduates are willing to travel further for the right position,” Mass confirms. The competitive nature of the marketplace has also forced many job seekers to chart a less-direct path to their chosen careers. Suddenly, they need an increased level of experience just to compete for what were once entry- level positions. “The career ladder has changed,” Crabbe confirms, adding that sometimes the first step is an internship, not the entry-level job. Those who do snag a good job right out of school face a different work environment than their parents. Twentysomethings find themselves thrown right into the fire as soon as they’ve settled into their cubicles. “I think the greatest challenge is the shortened learning curve for new hires,” says Lynn Insley, Director of the Office of Career Development at Stevens Institute in Hoboken. “Companies expect students to provide value as soon as they join the company, and that’s not something we were seeing prior to the recession.” Job seekers are also navigating an increasing number of positions without benefits—or “consulting opportunities” with no guarantee of conversion to full-time jobs.

Janet Jones, Interim Director of Career Services at Rutgers University, notes that some young people are even opting to bypass the traditional job search by going right into business for themselves. “The students who are most successful are those who have an entrepreneurial spirit, and are able to navigate the opportunities that are open to them,” Crabbe observes. She is speaking for Drew grads, of course. However, this view was shared by all of the college placement professionals interviewed for this story. And for the record, those professionals all represent institutions of higher learning in the Garden State. Their observations and advice are just as relevant to students attending schools outside the state. Indeed, let’s not forget that New Jersey’s greatest export is college students—and that the vast majority will be coming back. We’ll give them a reassuring hug, stuff a few dollars in their pocket, provide meals and laundry service, and offer them a place to rest their heads. And do so gladly. We just don’t want that situation to become a permanent one.

A New Look at the Way We Measure Excellence

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Having recently been coerced into a rousing game of Milton Bradley’s iconic preschool board game, Chutes and Ladders, I was reminded that the players don’t simply go up the ladders and down the chutes aimlessly. Each movement up begins on a square with a picture of a virtuous deed—for example, mowing the lawn or saving a kitten from a perilously high tree limb. The resulting square at the top of the ladder is a picture of the reward for that good deed, such as earning an ice cream sundae or money for a trip to the movies or the circus.

Conversely, reckless behavior—like eating all of the cookies or sneaking a comic book inside one’s history textbook—results in a quick trip down a chute as the deserved consequence of said choice. This popular pastime is perhaps one of the earliest values-based educational games a child might encounter. The message is unequivocal and morally relevant. But is this type of learning experience being woven into the curricula in our schools, where boys and girls spend the majority of their waking hours? Non-cognitive learning and concrete character development are crucial to the development of capable students and solid future citizens.

These qualities are particularly valuable when a young person enters the job market. The question is, how can skills such as resiliency, teamwork, creativity and respect actually be worked into traditional school curricula? These were among the “values” identified and selected in recent conversations among the heads of school of 25 institutions as part of an educational round-table. Other qualities included integrity, grit, empathy and zest—that enthusiasm that keeps us dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. Among the participants was Dr. Chad Small, Headmaster of the Rumson Country Day School in Monmouth County. In his view, these qualities need to be viewed by educators in the same critical context as, say, math and science. “What is crucial to us staying ahead as a country?” he asks. “What precisely is it that makes America great?” This is far from a rhetorical question. Indeed, it is common knowledge that American students have fallen behind other countries in their educational aspirations. This has triggered legislation such as No Child Left Behind.

The crux is that, to support and fund such initiatives, politicians are demanding “measurables,” which in turn lead to test performance-driven teaching. This heresy of emphasis on test scores may well be costing our children dearly, as teachers de-emphasize acquiring values as its own skill set—even though such values are vital to success in career and life, according to recent research. How do we help students in independent schools— and in all schools—to better meet the future head-on? Resilience, maintains Small, is one of the core character traits American schools should be striving to cultivate in their students. Dr. Randy Kleinman, Montclair Kimberley Academy’s Head of Middle School, adds that selfmonitoring, consistent effort and self-advocacy are a part of MKA’s educational mission. “While we do not specifically identify a ‘non-cognitive’ segment of our curriculum, the emphasis on development of those skills is woven into our teaching and the students’ learning experiences throughout our program.” Kleinman says that his faculty has studied the work of Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, who emphasizes the importance of “self-insight” and consistent, persistent effort as keys to success.

Dweck is among the many educators, ethicists and  academics pondering why attributes such as resilience have dwindled in recent decades. Dr. Richard Weissbourd, a Harvard professor, is also concerned about the priorities of parenting youth in America today. He calls upon parents to reflect upon the emphasis on their children’s happiness, self-esteem and achievement to the extent that these concerns appear to have usurped the importance of more character-driven values. Weissbourd goes on to say that American parents today are so concerned with their children’s achievement and happiness, that they shelter and hover—so much so that they attempt to envelop them in a stifling bubblewrap hug of insulation.

academics pondering why attributes such as resilience have dwindled in recent decades. Dr. Richard Weissbourd, a Harvard professor, is also concerned about the priorities of parenting youth in America today. He calls upon parents to reflect upon the emphasis on their children’s happiness, self-esteem and achievement to the extent that these concerns appear to have usurped the importance of more character-driven values. Weissbourd goes on to say that American parents today are so concerned with their children’s achievement and happiness, that they shelter and hover—so much so that they attempt to envelop them in a stifling bubblewrap hug of insulation.

Sparing kids adversity, he insists, actually divests them of coping skills. One might think that schools with religious affiliations would have some advantage in this respect, and perhaps they do. At Delbarton School in Morristown, implicit and explicit methods are used to teach skills like personal responsibility, resiliency, peer leadership, good decision-making, and effective communication. Brother Kevin M. Tidd, a member of the History and English departments who also heads up Delbarton’s Speech and Debate program, describes this focus as part of developing “a young man’s overall moral and religious character.” Union Catholic High School in Scotch Plains, has gone a step further and adopted the framework and holistic view developed by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, a national non-profit organization that advocates the “4 Cs” for student education—Critical Thinking, Communication, Collaboration and Creativity.

Assistant Principal Christine McCoid points out that, although “21st Century” connotes proficiency in technology and media, non-cognitive values such as cooperative learning, resiliency and leadership are always incorporated at UC. “We measure the success of our core value integration through observation rather than absolute quantification,” she says, acknowledging that these skills are difficult to put a number on. Small agrees. Education, he says, has been soft in the area of quantifying character development: “We’ve always known we’ve done it, but we haven’t always known how to measure how well we are doing at it.” With regard to such assessment, Small and the 24 other heads of school at the aforementioned round-table prevailed upon the Educational Testing Service (ETS) to step in.

Using the core values identified by the group, ETS created a questionnaire to be distributed to students designed to encourage each child to self-report data regarding his or her character engagement while in school. The collected data will be anonymous, so that no individual student will be singled out. However, a seventh grade class at one school may be compared with another seventh grade class in an attempt to quantify, for example, values such as persistence and creativity. Imagine if high school seniors touted their “Empathy Scores” instead of swapping SATs. SATs matter for 12 months of your life. Empathy matters as long as you live. The Morristown-Beard School makes the concept of “student engagement” a central priority of its curriculum, and has actually attempted to quantify this non-cognitive quality. “We have tried to measure this aspect of life at MBS through administering the National Survey of Student Engagement for the past two years,” explains John Mascaro, Dean of Faculty. “The results of this survey indicate a high level of student engagement, and we feel that this engagement is a key factor in the ongoing success of our students.” Scoring non-cognitive skills may strike some as a little crazy at first. But in this world of scorekeepers, by measuring something, we deem it a metric that matters, that determines progress over time, that encourages goal-setting.

Private school headmasters can look at their Boards (who demand accountability for the “value-added” programs) and say, “This is what makes us better.” That is precisely why independent schools have picked up the gauntlet on this critical issue of character education and quantification. They do not take government money, which means these institutions have the freedom to push the envelope and explore progressive ideas like establishing baseline scores for non-cognitive skills. Why does that matter? Because if you can score something, you can also legislate and fund it. And maybe, if you can put character development on an equal footing with reading, writing and arithmetic, you’ve found the key to putting our kids back on top of the heap. “You have to start somewhere,” Chad Small says. “You’ve got to get the conversation going.”

Editor’s Note: Erin Avery runs Avery Educational Resources (averyeducation.com). She holds Master’s degrees from Oxford and Yale Universities.

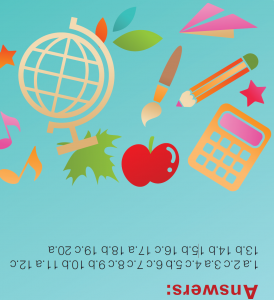

By the time students in New Jersey move into middle school, they have been thoroughly indoctrinated into the history, culture and infrastructure of the Garden State. Typically, this subject is taught as part of the Social Studies curriculum in fourth or fifth grade. The answers to these 20 questions can be found in any elementary school textbook…or you could just ask an 11-year-old.

The longest river contained completely within New Jersey is…

a) the Raritan River

b) the Shark River

c) the Hackensack River

The native people of New Jersey began farming the land…

a) about 10,000 years ago

b) about 5,000 years ago

c) about 1,000 years ago

The first European explorer to set foot on New Jersey soil was…

a) Giovanni da Verrazano

b) Henry Hudson

c) Cabeza de Vaca

The first permanent Dutch settlement in New Jersey was called…

a) New Netherlands

b) New Amsterdam

c) Bergen

Revolutionary War heroine Molly Pitcher participated in…

a) The Battle of Trenton

b) The Battle of Monmouth

c) The Battle of Short Hills

The city of Trenton became New Jersey’s capital in…

a) 1770

b) 1780

c) 1790

Between 1918 and 1929, the number of cars in New Jersey rose by more than…

a) 250,000

b) 450,000

c) 650,000

Harriet Tubman’s base of operations for the Underground Railroad was…

a) Glassboro

b) Camden

c) Cape May

George McClellan, general in chief of the Union Army, was from…

a) Westwood

b) West Orange

c) West New York

Camp Dix (aka Ft. Dix) was built to train troops for…

a) The Spanish-American War

b) World War I

c) World War II

The waterway that brought coal from Pennsylvania to New Jersey factories in the 1800s was…

a) The Morris Canal

b) The Erie Canal

c) The Raritan Canal

The number of New Jerseyans who served in the military during World War II was just over…

a) 300,000

b) 400,000

c) 500,000

The postwar builder who turned Willingboro from a town of 600 to a suburb of 40,000 was…

a) William Carteret

b) William Levitt

c) William Hovnanian

The Garden State Parkway opened…

a) in 1949

b) in 1954

c) in 1959

The governor who initiated the first state income tax, specifically to support New Jersey’s schools, was…

a) Frank Hague

b) Brendan Byrne

c) Jim Florio

The state’s famous business slogan is…

a) Business is ripe in the Garden State

b) Your future is just an exit away

c) New Jersey makes, the world takes

The two parts of the legislative branch in New Jersey are…

a) the Senate and General Assembly

b) the Governor and Congress

c) the Judicial and Fiscal

The Pledge of Allegiance was given as the national oath in 1893 for the first time at…

a) The Newark Train Station

b) The Twin Lights on the Navesink Highlands

c) The steps of the Trenton Courthouse

Poet Walt Whitman lived out his final years in…

a) Saddle River

b) Weehawken

c) Camden

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark opened in…

a) 1997

b) 1999

c) 2001 A passing grade is 13. Brave enough to check your work? You’ll find the answers in the box at right…

Images courtesy of Upper Case Editorial Services

Down the Rabbit Hole

Where is video gaming taking our kids?

Remember the good old days, when homes actually had dens and family rooms? These physical spaces still exist, of course, but thanks to quantum leaps in computing power—and profound shifts in what constitutes social interaction— they have become more and more “virtual.” What we used to call dens we now refer to as home offices. That makes sense, at least. But what of the family room, that once-sacred place where Scrabble and Trivial Pursuit provided the glue for togetherness? In the blink of a generation, it has become the rabbit hole down which ’tweens, teens, twenty-somethings and—in startling numbers—grown-ups disappear for hours on end to play video games. The gaming phenomenon has become a subject of growing interest and concern among educators, employers, psychologists and parents. It has created obstacles and opportunities that didn’t exist a couple of decades ago, and has changed the very definition of what we think of as play.

A LITTLE HISTORY Gaming wasn’t much of an issue when it began in the 1970s. In fact, the word gaming itself did not yet exist. Pong and Space Invaders could be found in arcades and bars, fascinating the quarter-pushers, but the appeal proved limited. However, a new culture had been born. Indeed, 10 years later, Nintendo consoles were everywhere, and games like Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., Zelda, and Metroid had parents enforcing strict bedtimes for their prepubescent offspring. The video game industry continued to grow, technologically and financially, as it entered the 21st century. With the doubling of computer power every few years, games had become more complex, more sophisticated and more addictive. And the money being spent on video games by the public was absolutely staggering. Grand Theft Auto IV was released in 2008 and sold six million units, grossing $500 million, in its first week of release. Game developers, now working with squads of brilliant artists, writers, and coders, had tapped into a demand that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier. Games were modified to be playable not only on hot-selling consoles like Xbox and PlayStation, but on home computers, laptops, tablets and, inevitably, smartphones. With these remarkable advances came a backlash. The assaults came from many quarters—gaming was blamed for teen violence, plummeting verbal abilities, rampaging obesity, and plagues of ADHD, autism and pathological solipsism. College grads, who “should have been” out looking for jobs and spouses, were locking themselves in their darkened rooms with enormous supplies of tortilla chips and diet soda, playing everything from the latest John Madden NFL (total sales for the series estimated at $3 billion) to Guitar Hero, Tiger Woods Golf or Call of Duty.

A LITTLE HISTORY Gaming wasn’t much of an issue when it began in the 1970s. In fact, the word gaming itself did not yet exist. Pong and Space Invaders could be found in arcades and bars, fascinating the quarter-pushers, but the appeal proved limited. However, a new culture had been born. Indeed, 10 years later, Nintendo consoles were everywhere, and games like Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., Zelda, and Metroid had parents enforcing strict bedtimes for their prepubescent offspring. The video game industry continued to grow, technologically and financially, as it entered the 21st century. With the doubling of computer power every few years, games had become more complex, more sophisticated and more addictive. And the money being spent on video games by the public was absolutely staggering. Grand Theft Auto IV was released in 2008 and sold six million units, grossing $500 million, in its first week of release. Game developers, now working with squads of brilliant artists, writers, and coders, had tapped into a demand that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier. Games were modified to be playable not only on hot-selling consoles like Xbox and PlayStation, but on home computers, laptops, tablets and, inevitably, smartphones. With these remarkable advances came a backlash. The assaults came from many quarters—gaming was blamed for teen violence, plummeting verbal abilities, rampaging obesity, and plagues of ADHD, autism and pathological solipsism. College grads, who “should have been” out looking for jobs and spouses, were locking themselves in their darkened rooms with enormous supplies of tortilla chips and diet soda, playing everything from the latest John Madden NFL (total sales for the series estimated at $3 billion) to Guitar Hero, Tiger Woods Golf or Call of Duty.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

WHO’S GETTING HURT? There is widespread agreement that some video games— specifically those emphasizing stealth, violence, misogyny and lawlessness—are unlikely to be positive forces. This is particularly true in the case of pre-teen and adolescent youth, as well as in adolescent males, who tend to lock into these ninja paradigms. Many games enable the player to experience adventure and danger without developing a realistic appreciation of the consequences. Experts are quick to point out real issues even with the seemingly innocuous games that allow kids to experience the mastery of a sport or activity without acquiring the patience and persistence to study and practice. For example, while a child can quickly gain some mastery over any of these games, by contrast an elementary grasp of karate or baseball requires years of constant practice and respect for authority. The boredom and physical discomfort of actually engaging in a sport pay dividends that sitting alone pushing buttons never will. But don’t try telling that to a child who is slugging the ball 500 feet over Yankee Stadium’s virtual fence. Some people go so far as to claim there is a one-to-one relationship between gaming and illegal/antisocial/self-destructive activities. That probably stretches the point a bit too far. If memory serves, teenage boys are not exactly hard-wired to be risk-averse. The better debate is whether certain kids are genetically programmed to be sociopaths. Every time another school shooting occurs, video games are high on the list of proximate causes—right after drug abuse, parental abuse, and getting ditched by the prom queen. This leads to analyses that defy the basic rules of scientific research: clearly defined parameters, repeatable results, and objective evaluations. As yet, no one has produced a shred of evidence that video games turn troubled boys into monsters.

PARENTAL PERSPECTIVE That being said, a search through the archives of the American Psychological Association web site doesn’t leave a worried parent with many clear answers. For every pro there seems to be a con, and vice-versa. Video gaming may indeed encourage violent behavior in some (possibly predisposed) kids. Sexual stereotyping and objectification also broadens the gender gap. Then again, gaming helps develop better hand-to-eye coordination, faster reflexes and better processing skills. Games may even help to treat dyslexia. The more you read and research, the clearer it becomes that nothing resembling a unified approach to gaming as a potential threat to young people’s development has yet emerged. Nor should anyone expect it to. Concerned parents might be better served by developing some basic tools to encourage moderation in gaming. Because of the popularity of video games, completely eliminating them from a child’s life might be difficult. But according to the non-profit Palo Alto Medical Foundation, you can decrease the negative impact that they have by… • Knowing the rating of the video games your children play • Not installing video game equipment in your children’s bedroom • Setting limits on how often and how long your children are allowed to play video games • Monitoring all of your children’s media consumption, including television, movies and the Internet • Supervising your children’s Internet use (there are now many video games available for playing online) • Taking the time to discuss with your children the games they are playing or other media they are watching— how they feel about what they observe in these video games, television programs or movies • Sharing with fellow parents information about certain games or ideas for helping each other in parenting Is it an uphill battle? Of course it is. Parenting is an uphill battle. Are game designers targeting young people? Of course they are—but no more than manufacturers of clothing or fast food or beverages or cosmetics. Commercials for prescription drugs and law firms target adults. Welcome to capitalism. The better question might be: Are we doing enough to identify the kind of at-risk young men and women whose behavior is susceptible to the negative influences of some video games?

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

THOUGHTS FROM THE GAMING WORLD Every so often there is a groundswell of interest in regulating the content of video games. As any lawyer will tell you, that gets tricky because the industry will almost certainly put the First Amendment in play. Perhaps it’s not the industry picture that needs to be altered, but the parenting picture. Consider the viewpoint of one young game developer who recently cashed an eight-figure paycheck after selling his company to a major software corporation. His take is that video games have provided many parents with a cheap, popular, absorbing babysitter—one that keeps Junior at home rather than running in the mean streets. “If you don’t think your child should be playing,” he says, “maybe you should buy her a book, or teach him how to do woodworking, or get them aikido lessons. Maybe it’s not the kids who are being irresponsible, but you. There’s nothing inherently evil in gaming, any more than there is in ice cream—it’s not an unqualified evil like tobacco, crystal meth, binge drinking, or unsafe sex. It’s fun, it has positive qualities, it can even be educational. But you need to help your kids develop values and priorities and a sense of balance.” Tens of millions of children have access, by one means or another, to a wide range of video games. Some are despicable, yet others are clearly educational and developmentally sound. Some perspective is called for here. Remember that the overwhelming majority of these children will have their hearts broken, get zits, fail to make the varsity, and wallow in the certainty that their parents neither love nor understand them—all before they reach voting age. Amazingly, they will go on to lead reasonably productive and happy lives.

The Cold, Hard Fact

New Jersey’s number-one export is college-bound seniors. During each application period, the nation’s top colleges are flooded with applications from the Garden State. It’s a numbers game that works against our kids. However, if you do a little homework, there are definitely ways to make the numbers start working for you. So with the dark winter of college acceptance letter anticipation upon us, let’s look back at the 2011 application period and see what it has to teach next year’s juniors and seniors. First things first. For the mournful applicants who threw their hats in the Early Decision ring at Ivies such as Brown University—which accepted only 900 of the 2,900 applications—ED now stands for Early Disappointment. Ditto Northeastern, which deferred an inordinate amount of highly qualified Garden Staters. The story was the same in one popular school after another. Indeed, many of our young and talented “intellectual-istas” are now pacing the library aisles hoping that fat envelope shows up in April…and wondering what went wrong. What went wrong is that they all chased after the same hot colleges, essentially forcing the hands of admissions officers to say No. Geographical diversity is a high priority at most top schools. Translation: we can only take so many kids from New Jersey. How do you swing those odds in your favor? That process starts during the critical first steps in the college search and application process.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

MANAGING EXPECTATIONS In order to have successful outcomes, an ounce of expectation management is worth any of those one-pound college guides you’ll be buying at the local Barnes & Noble. Understand where your college-bound child fits into the overall admissions picture. For instance, while GPA is a healthy indicator of a student’s success in college, a 3.0 at The Lawrenceville School is quite different than a 3.0 at nearby Trenton Central High School—with due respect to both. Standardized test scores are also useful in helping a student (and more importantly his or her parents) determine whether or not the student is likely to be admitted or likely to be rejected by a given college. Beyond those quantitative indicators, one must acknowledge that college-admission decisions can also turn on relationships. In addition to an “in” or connection at a school, however, students must also demonstrate a knowledge of the culture and mission of that college—and articulate that interest throughout the application. To do so, successful applicants must really know the colleges to which they are applying. And if that school is a “hot” school, well, they really need to bring their A-Game to the application.

IDENTIFYING A HOT COLLEGE Long before work begins on applications, you can start creating a wish list of schools. That list will almost certainly be populated by a number of hot colleges. That’s fine and that’s fun, but look at those schools and ask yourself, how many of them were popular five or ten or fifteen years ago? Where I’m going with this is that there are a lot of schools right now primed to “join” the hot list. Your job is to identify them before everyone else does. Beating the competition to a hot college is much like picking a stock. First, observe how the school performs over a period of time. Frankly, this is one of the major reasons families come to people in my business. Educational consultants visit numerous college campuses, read The Chronicle of Higher Education and other pertinent periodicals, attend symposia and present at conferences, and nurture ethical relationships with admissions representatives—all on their clients’ behalf. Of course, you can “day-trade” and do the work yourself. Begin by identifying and tracking a college of interest. Some points to consider are: Has this school made a jump in rankings and/or is it rankings-aware? Has there been a recent shift in leadership? Are the current students and grads singing the school’s praises? How strong are the career services and what companies recruit on campus? This information isn’t always easy for a layperson to access or understand, but the more you amass, the better your results will be. One good publication that is literally the length of a church bulletin is the CollegeBound newsletter (collegeboundnews.com), which is very readable and provides real-time admission numbers. I tweet these bitesize stats daily.

NAMING NAMES Without specifically advocating these institutions as bestfits for any individual, here are a couple of examples of what I’m talking about. Ever heard of High Point University, in North Carolina? If not, you will. I have been following High Point for some time now. It has all the earmarks of a hot college due to the leadership of its president, a former CEO with a business-savvy approach to student satisfaction and success. The graduating senior entering just four years ago probably would not be accepted this year in the Early Action pool. Size, location and price-point make this college one to watch. Closer to home, I also like what I am seeing at Drexel University. It stands out among the growing number of colleges offering co-op opportunities. Co-op stands for “cooperative,” which is an option at some colleges that enables students to earn course credits for work experience in the form of approved internships (which are frequently paid!). This option is best suited toward pre-professional students who are actively preparing for a career in a specific field, learn-by-doing students, and students who want “a foot in the door.” An inordinately large number of students are hired by the firms at which they completed their co-ops. It’s not hard to see why schools offering co-op programs have seen their popularity and demand rise over the course of the past three years—while at the same time the precarious economy has called into question the value of the liberal arts education in favor of a skill- and career-based undergraduate education. Making industry connections and building up a résumé all appear to be de rigeur at this juncture, but as a purist, I beg to differ that the liberal arts and sciences are passé. In favor of this argument, take Bucknell University. Tucked away in Western Pennsylvania, this Division I college has grown extremely selective in its admissions decisions over that past decade. The emphasis on interdisciplinary study and engaged learning is helping Bucknell produce superlative leaders and self-starters.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

DOLLARS AND SENSE As college costs skyrocket and family budgets tighten, the “default” pick for many students is the state school or community college. However, that is not necessarily where the higher-education bargains are. Indeed, the changing economy has created some eye-opening options—and potentially an entirely new class of hot colleges. Parents of 10th and 11th grade students at this juncture may want to consider the fact that most students at independent institutions pay less than the published tuition price. According to College Board’s “Trends in College Pricing,” the average student paid $17,000 less than the sticker price at independent colleges and universities in the U.S. in 2010-2011. How is that possible? Federal grant aid for students at state schools is about $3 billion a year. Meanwhile, institutional grants—the free money given to students by the colleges they attend—is around $20 billion! So opting for the state university or community college without exploring the estimated cost after Gift Aid could cost you in the long run. Gift Aid is free money for college that students do not have to pay back. It comes in the form of tuition discounts off the sticker price for attractive applicants. A strong academic profile and high-test scores—which will in turn boost a college’s rankings—are two reasons why colleges would offer Gift Aid to an applicant. By the way, as of last December a mandatory net price calculator must appear on all college web sites. This is a groundbreaking change intended to help families get an early read on the true cost of college. Though each site’s calculator will vary, some will calculate Gift Aid. The bottom line is that the college application process can be a messy one, but it’s definitely manageable. Of the many things that are crucial to keep in mind, perhaps the most important is that college is not a one-size-fits-all prospect. The right school, hot or not, is out there for your collegebound son or daughter. The more effort you put into identifying that school, the better your chances for a positive outcome.

Editor’s Note: When Erin is not authoring articles, she runs Avery Educational Resources (averyeducation.com). She also does pro bono work with children who lost parents on 9/11. A Division I varsity athlete and a competitive Irish step dancer, she holds two Master’s degrees from Oxford and Yale Universities, respectively.

’Tis the season. No, not of family gatherings and holiday cheer. For college-bound seniors and their parents, it’s crunch time.

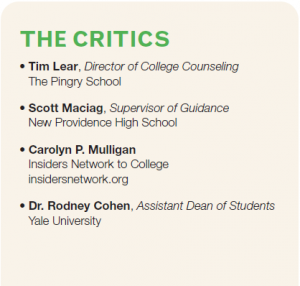

College admissions officers are bracing themselves for the tsunami. Over the next few weeks, the steady stream of applications they have been wading through will turn into an unstoppable torrent. One of the countless charms of the Internet is that it has made the process of applying to multiple schools incredibly simple. A generation ago, high-school seniors would pick a handful of schools—including a reach and a safety—fill out the paperwork by hand, lick the envelope, stamp it, and send it off. Thanks to the common application (aka The Common App) and the wonders of technology, today every one of the 3.5 million teenagers thinking about college can apply to 20 schools with only slightly more effort than it took to lick those envelopes. One thing about teenagers hasn’t changed. No matter how easy the computer has made it for them to apply to college, they somehow find a way to turn the process into a full-on heart attack anyway. The majority of kids will be pushing the SEND button on their applications just a day or two before the deadline. Some will take it down to the final minutes or seconds. While frustrating for parents, engaging in this type of brinksmanship isn’t what should concern the moms and dads of college-bound seniors. The critical time-management issue is making sure that enough thought and effort have been devoted to the creation of an essay for the common application that grabs the attention of even the most overwrought admissions officer. It is the piece that tells a college who a young person is, and helps determine whether he or she would be a good fit for the school. Is your senior‘s essay done? I’m guessing the answer is no. Remove your fingers from around your child’s neck for a moment and take a look at what another kid did. I asked four professionals in the college admissions process to critique this essay. I made it clear that the writer had already matriculated, so we weren’t fishing for praise. Instead, we were looking for specific, constructive criticism that would help members of the Class of 2013 evaluate their college essays as the application deadline nears….

THE ESSAY When life hits you in the face, react with your head, not your hands. I never really knew what my parents were talking about until that awful Sunday afternoon in May. I had struck a section of guardrail with such force, and at such an unusual angle, that it lifted two of the supporting stanchions completely out of the ground. Luckily, I was unhurt. The culprit was long gone. Not a drunk driver. Not some idiot wolfing down a Quarter Pounder while texting on his cell phone. Rather, it was an enormous beetle that had flown through the open, driver-side window—smack into my face. A novice behind the wheel, I swerved left, over-corrected right, and finally lost control at 50 miles per hour. Precisely six weeks after posing for my first driver’s license photo, I had become a cliché. I was shocked and angry and embarrassed. The car was a twisted wreck. It had collapsed around me, absorbing the energy of my high-speed, metal-on-metal encounter. Totaled. It was only later, when I saw photos of the car and revisited the scene of the accident, that I realized how fortunate I was. Had I swerved 20 feet sooner I might have been cleaved by a telephone pole. Had I left the road 20 feet farther down the hill, I would have launched myself into a ravine. Teenagers are not wired to contemplate their own demise, yet whenever I drive past this spot it is hard to think of anything else. In time I realized something slightly more profound. By handing the keys to a newly minted driver, mom and dad were giving me that first terrifying (for them) taste of true independence that’s part of the letting-go process of parenthood. While all I saw was the upside, they had quietly thought through the downside and purchased the automotive equivalent of a Panzer—a used Audi wagon that was basically conceived and constructed to crash into guard rails and deliver young drivers back to their parents older, wiser and relatively unscathed. I might mention here that I had lobbied briefly for a Thunderbird convertible (yeah, dream on!). It’s less than a year later and my parents are now preparing to hand me the keys to a college education. They will be writing out another large, painful check and making me the driver of my own life. How terrifying this is for them I can only guess. Recently, I found myself telling a friend “when life hits you in the face, react with your head, not your hands.” She wasn’t really sure what I was talking about, but a few weeks later, she found herself wrapped around a telephone pole thanks to an adventurous squirrel. At this point, it is safe to say that almost everyone in our group of friends has both heard and understood this bit of wisdom. Of course, part of giving advice is accepting that advice yourself. And in that spirit, I would like to tell my parents what I have learned. Next time I will react with my head and not my hands. That’s a no-brainer, so to speak. And although I still feel indestructible, I also know grave consequences await both my actions and in-actions. Mostly what I’d like to tell them is that in choosing a college, I now know I’m looking for the Audi, not the T-bird. I’d like to tell them…but I won’t. As they taught me, sometimes you just have to figure things out for yourself.

THE FEEDBACK All four of our experts agreed on two things. The essay demonstrated excellent writing skills, but also fell short of that certain something admissions officers love to see in an essay: Wow Factor. “I really enjoyed the opening. It grabbed my attention and piqued my curiosity,” says Lear. However, he  maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading

maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading  thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

Editor’s Note: Assignments Editor Zack Burgess writes on culture, politics and sports for a number of publications and web sites. His work can be seen on zackburgess.com. The young author of the essay in this story was accepted by (and now attends) a Top 30 university.