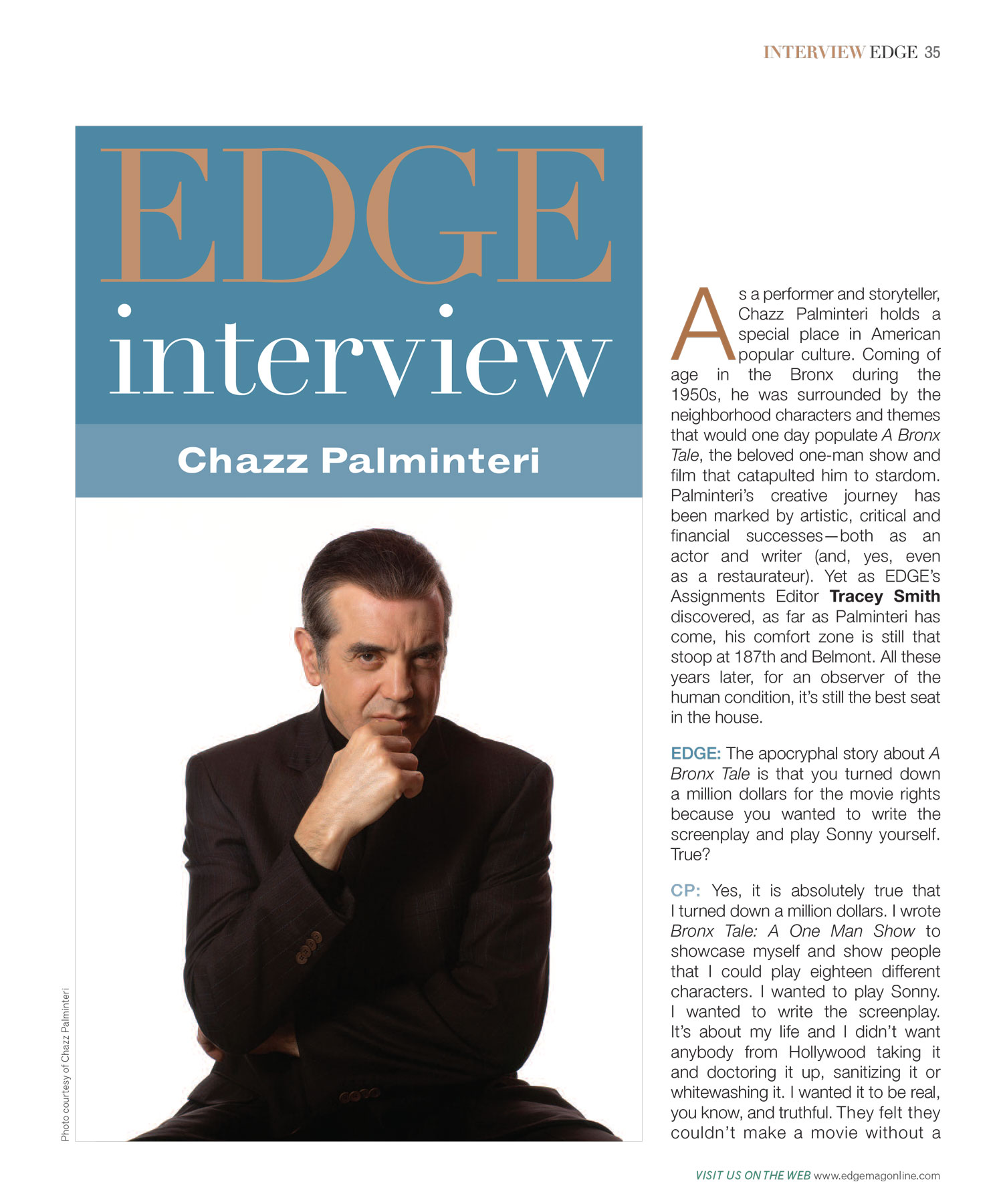

Anyone who questions whether acting is a craft needs to spend a little time with the cast of a play like Stick Fly, which opened to rave reviews this past winter at the Cort Theatre on 48th Street. Produced by Alicia Keys and directed by Kenny Leon, Lydia Diamond’s engaging family drama explores themes of race and class through the story of an upper-class African-American family. While this may be unfamiliar territory for most Broadway theatergoers, the two male leads of Stick Fly are instantly recognizable. Mekhi Phifer (ER) and Dulé Hill (The West Wing and Psych) rank among the most beloved and talented ensemble television actors of our time. Hill is an old hand where Broadway is concerned, while for Phifer Stick Fly marks his debut. EDGE Assignments Editor Zack Burgess met with the co-stars before a performance at the Cort over the holidays. Three-way Q&A’s can be tricky—especially with so much ground to cover—but as usual, Zack just pointed his subjects in the right direction and they took it from there.

EDGE: Did either of you have a professional relationship with Alicia Keys prior to this production of Stick Fly?

Dulé Hill: No. But I have always been a fan of hers. Who’s not a fan of hers?

Mekhi Phifer: I knew her, but of course not to the level of our friendship since this project got started.

DH: I had done a version of Stick Fly about five years ago in L.A. It was a staged reading with mikes. It kind of reminded me of old-school radio. It was fun. I hadn’t thought about it since then, and then I got a call back in the summertime to do a project. I knew they had an offer out to Mekhi, which really piqued my interest. Once I was told the name of the play, I said I’m in. Alicia’s involvement was the icing on the cake.

EDGE: You both have done lots of television and film work so you have a good background in terms of shared experience. The exception is probably that Dulé has spent time on the Broadway stage. Mekhi, how has Dulé helped you adjust to performing on stage?

MP: Dulé has done Broadway four times. I’ve never done a play, so I’ve asked him a lot of questions. It’s always helpful to be surrounded by people who are veterans and who are good at what they do—who know what is entailed in making this thing work. Being able to go to Dulé was very helpful for me to get acclimated to this environment.

DH: Remember that the other pieces have mostly been musicals. This is only the second produced play that I have done. So it’s still kind of a new world for me. I’m not going to be putting on any tap shoes or singing.

EDGE: Dulé, what did you see as Mekhi’s immediate strengths in terms of stagework when you guys started rehearsals back in the fall?

DH: It comes down to being a brilliant actor. He brings it every time. That’s the case whether he’s on ER playing Dr. Pratt or the star of Paid In Full, coming on Psych or playing Flip in Stick Fly. That alone is it. Having those skills. There are things you have to do when you’re dealing with the stage versus film and television, and Mekhi took everything in,

learned and adapted. He asked questions and processed information very quickly. You wouldn’t know that this is the first play he’s ever done. I really respect him for that.

EDGE: Dulé, are there any parallels between the LeVay Family in Stick Fly and your own experience growing up in New Jersey?

DH: I grew up in a middle-class family, although I don’t think we had anywhere near the type of money of the LeVays. But I definitely relate to the LeVays’ dysfunction. I have a great family, but we have our level of dysfunction, too. There are things we don’t talk about. We don’t always address issues when we should and they end up simmering underneath and then exposing themselves in other areas.

EDGE: What about similarities to your character, Spoon?

DH: Spoon is trying to figure out where he wants to go in life. And that is foreign to me because I started doing theatre at the age of ten, and started tap-dancing when I was three. I’ve always been on a journey of self-discovery and owning who I am as Dulé—not trying to fit into the mold of what other people think I should be. Spoon doesn’t own his vision. He starts to figure it out during the play, but in a way his family never supported him or gave him the opportunity to really find out what he wanted to do. I’m very thankful that my parents supported me, exposed me to new experiences and let me find where I want to go in life.

EDGE: Is that what Stick Fly is about?

DH: It’s about family dysfunction, self-identity…and daddy issues.

EDGE: Daddy issues in what respect?

DH: The idea that, when you’re a child, your father is perfect. For instance, I love my dad to death, but growing up there’s this issue of trying to fit into the mold of who you think you should be because of your father. Then one day you realize that your father is a man just like you. He has his own faults and Achilles’ Heel.

MP: My character, Flip, emulates his father. He’s a doctor, like his dad. He’s just living life. He’s off the cuff. Flip has what is seemingly a closer relationship with his father than the one Spoon has. But I think what makes Dulé’s character stronger than mine in certain respects is that Flip took the more accepted route by becoming a doctor.

EDGE: What was your family background like, Mekhi?

MP: I grew up in a single-parent home and never met my Dad. At the same time, my mother was a schoolteacher, a dancer and a choreographer. She always stressed academics, but she was also about the arts. There was never one way to do something. She favored an obtuse way of thinking versus an acute way of thinking. So my mom wanted me to have great grades and she looked over my homework. But she was always supportive of the arts. So when I was a kid and I would do little talent shows, or rap in freestyle and battles, she was always very supportive.

EDGE: What nuggets of wisdom have you guys picked up from your co-stars over the years?

DH: We’ve worked with phenomal co-stars.

MP: I agree, we’ve both been blessed to work with some dynamite co-stars.

DH: On The West Wing, Martin Sheen used to say to me, “It’s got to cost you something. If it doesn’t cost you something, then it’s meaningless.” Whether it’s the journey of the character or you as an individual, you really have to put yourself into it. Something—time, energy, whatever— has to be sacrificed if you’re going to have a successful career. For example, if I’m hanging out all night partying and then try to come on stage the next day, it’s just not going to work. You have to make choices and say, “This is where I want to go. This is what I want to do.” That always stuck with me. What also struck me about Martin was his humanity, how personal and gracious he was with everybody. I try to take that part of him and apply it to my own life.

MP: The first piece of advice that really stuck with me came while I was doing my second film, Tuskegee Airmen. Laurence Fishburne told me then that “less is more”— especially when you’re dealing with film and television. Another piece of advice I got was from Bill Cosby. He said somebody had asked him what was the key to success, and he said he didn’t know, but he did know the key to being unsuccessful, and that’s trying to please everybody. Those two poignant statements have stuck with me throughout my career.

EDGE: From Martin Sheen and Laurence Fishburne we move on to Jon Lovitz…Mekhi, what do you take away from a crazy comedy like High School High?

MP: Jon Lovitz was wonderful. We were all young in that movie and I always remember him being so nice. He was extremely successful at that point, just coming off of doing SNL. That was early in my career and it was a little bit of a whirlwind for me. But Jon’s one of those guys that will stop you on the street and talk to you, and after awhile you’ll be like, All right Jon, enough is enough. Enough jokes. I’ve got to go. So like Dulé said about Martin, yeah be successful, but be gracious as well. Live life and get to know more people.

EDGE: Dulé, you got to know Wesley Snipes working together on Sugar Hill. What insights did he give you as an actor?

DH: There was one thing that Wesley told me that stuck with me. I had just gotten to L.A. and it was right before I got The West Wing. I was auditioning for stuff and I wasn’t getting the roles, the scripts weren’t very good, and I was going to get dropped by my agent. I ran into Wesley one day and he said, “If there’s always one way, there’s always another.” I asked him what he meant by that and he explained that if you see a bunch of people going up a hill and falling back and not making it through, then try to look on the other side. There’s not just one way to get to your destination. I don’t know what he meant for me to receive from that, but it always stuck with me. From then on I’ve always looked for different angles on how I approach a character, and my career.

EDGE: I am curious how the involvement of a major musical personality changes the culture of a movie or a TV show or a stage production. For instance, Mekhi, when you worked with Eminem on 8 Mile, was that a very different experience than the other films you’ve done?

MP: It was great. Pure fun. I’m 26, 27, we’re in Detroit, Eminem is at the apex of his career. We had a month of rehearsals so that Eminem could get dialed in. We partied hard and it was fun. It was a great experience working with a director like Curtis Hanson and all these actors who were relatively unknown at the time. We had a blast. What I loved about Curtis was that he trusted us. Even when we were doing the battles—that stuff was not scripted. And the people in Detroit were great. What made those battle scenes real is that those people were real people. They were not day-to-day extras, they were real people from the neighborhood.

EDGE: Every successful actor has that role that he almost got, but it went to someone else. So tell me, each of you, what was the “one that got away”?

DH: That’s a tricky question, because if it got away then it was never really mine. There are roles throughout my career that I wanted, but I’m very happy for the actors who got them. One was Savion Glover’s role in Tap, because I’m a tap dancer. To work with Gregory Hines, Steve Condos, Harold Nichols, Jimmy Slyde and Sammy Davis, it really hurt when I didn’t get it. I just wanted to be in that space with those great actors. A lot of those guys started passing on right after that. Antwone Fisher was another role I really wanted. I would love to have shared the screen with Denzel Washington for that amount of time. Derek Luke got the role and Derek’s a good friend of mine. It really exploded his career. I was happy for the actors who got those parts, but I would be lying if I said I hadn’t wanted those roles.

MP: Right after I did Clockers with Spike Lee, I auditioned for Dead Presidents. I was right down to the wire for the role of Anthony and they decided to go with Larenz Tate, which was fine because Larenz is a friend of mine. They were shooting in New York, it took place in the Bronx, and the Hughes brothers were just riding high off Menace II Society. I remember meeting with the casting director, who thought they were going to give me the part. But I guess the Hughes brothers already had a relationship with Larenz—who had stolen the show in Menace II Society. I guess they figured We’ll ride with him.

EDGE: Have you ever walked out of an audition thinking you’d messed it up?

DH: Going back to Antwone Fisher, I got a chance to read with Denzel. Now normally after I read a script, I don’t usually get caught up in the things that are in parentheses— words like ANGRY or UPSET. I leave that alone and go with my own journey. For some reason in that particular situation, I saw the word ANGRY sticking out. So when I’m in the room and it’s me with Denzel, that word kept popping into my head. So I’m reading and I’m being angry. The first thing Denzel said to me was, “Why you so angry?”

EDGE: But your career survived.

DH: It did. So to all the people out there, I say just because you mess up on one thing doesn’t mean it’s the end of the world.

EDGE: Back to Stick Fly—Dulé, how does this cast compare to some of the others you’ve worked with?

DH: One of the perks of being in this business is just the camaraderie that exists with the people we work with. That’s what makes a show like Psych successful. These people are really good at what they do. And they also happen to be really nice people—people that you want to hang with and have drinks with later. Look at Stick Fly. When you work with actors like Ruben Santiago-Hudson, Tracie Thoms, Rosie Benton—they challenge you just to step up to another level. Ruben is a bona fide professional veteran, Tony Award winner and dynamic actor. You can’t half-step it with Ruben. It’s not going to happen. They’re all phenomenal actors. Then you get blessed to be in a situation where you’re seeing someone like Condola Rashad—someone who is already great, but her career is just getting started. I’m really honored to be on the stage with her. She’s knocking it out of the park now, but in ten, fifteen years I truly believe I will be saying that I was a part of her journey to greatness.

EDGE: What does your director, Kenny Leon, bring to the show, and how might someone in the audience at Stick Fly experience that?

MP: Kenny brings a realism to it. I’ve been to many Broadway shows and the worst thing in the world is to sit there and you’re bored out of your mind. You start fidgeting, you start falling asleep. Kenny not only stresses pace, but telling a story and being good at what you do as an actor. A good analogy would be a dog race. We, the actors, are the rabbit. The audience is the dog. We want them to come up to our speed, and I think we succeed. Doing a play is a totally different machine when it comes to directing. I love Kenny’s direction.

DH: I have to say that most of the directors I have had a chance to work with have been brilliant. But there are things about Kenny that remind me of George Wolf, the director of Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk. They are both very specific about every little detail. Everything we’re doing on stage in Stick Fly is meant to draw the audience’s attention to where Kenny wants it to be. That’s cool, because sometimes as an actor you forget those things.

Editor’s Note: Zack Burgess writes about politics, sports and culture for a variety of publications and web sites. You can read his work at zackburgess.com.

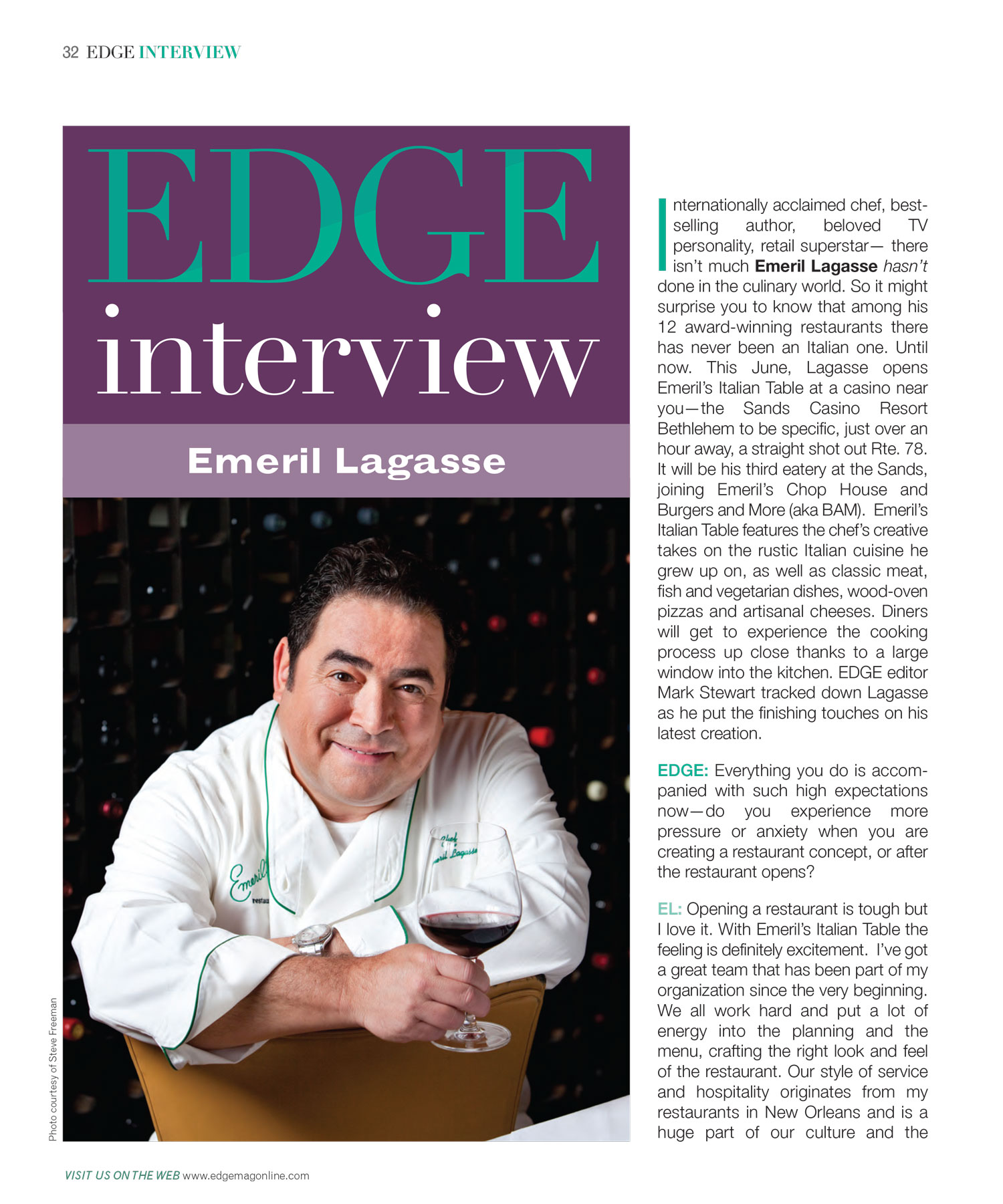

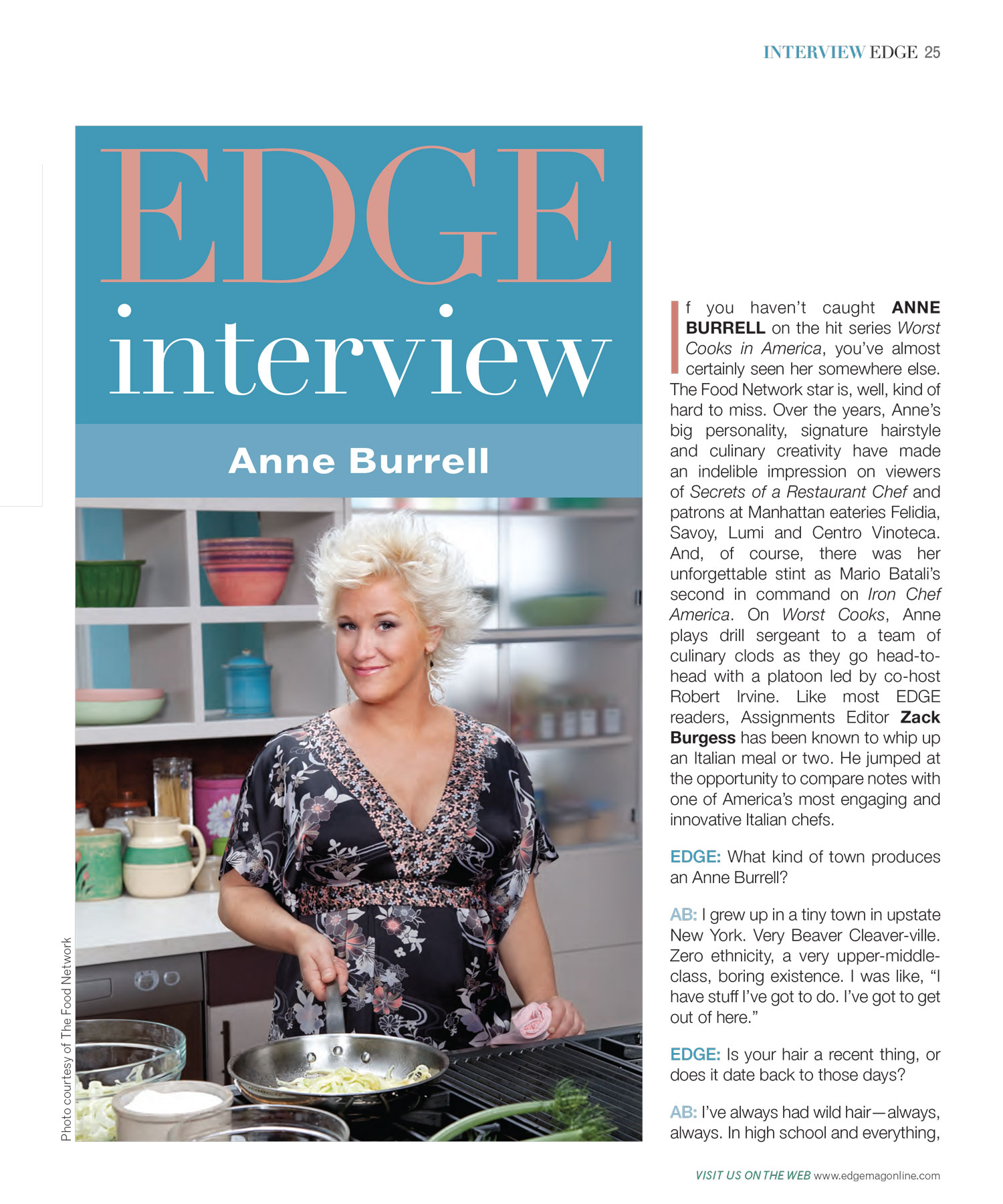

Fashion doesn’t just exist in clothes. Fashion lives in an idea. It is shaped by what and, more importantly, who is happening at the moment. Kimberly Landau of CoCo Pari travels the globe and stays on top of the trends to ensure that her stores in Red Bank and Deal always have the latest in designer clothing and shoes, from swimwear to exquisite and elegant eveningwear to everything in between. Everything is hand-selected, highly edited and well-curated. EDGE regular Diane Alter managed to get Landau to slow down for five minutes and go over some fine points on holiday style, resort wear, designer footwear…and what it truly means to shop for fashion.

EDGE: What kind of conversation do we need to have in order to get me into a great holiday party outfit?

KL: We should discuss what kind of event you are attending, what time of day it will be, what you want say with your outfit and perhaps what celebrities or stylists you want to emulate. We will outfit you from head to toe. We will even help you accessorize.

EDGE: Are there certain designers who seem to click with your customers?

KL: Yes! Herve Leger is certainly one. His clothing is very slimming. They make women look two sizes smaller. I don’t buy clothes that are trendy or retro-hip. I stay with designs that are feminine. My clothes are different and women like that.

EDGE: You personally do all the buying for CoCo Pari?

KL: I do. Me alone. So I know what I have and what is coming in. I buy items that match and complement each other. In department stores, you have to go to different floors—or a different store altogether—to complete an outfit. At CoCo Pari, you can find it all right here. Our clothes and shoes blend. They flow.

EDGE: Would you say that’s the key difference between working with CoCo Pari as opposed to window-shopping my way down Madison Avenue or store-hopping at a high-end mall?

EDGE: Would you say that’s the key difference between working with CoCo Pari as opposed to window-shopping my way down Madison Avenue or store-hopping at a high-end mall?

KL: Unlike department stores, where the saleswomen are simply vying for the largest commission, we truly want to make our customers look and feel their best. So I’d say that the biggest and perhaps the most distinct advantage of shopping at CoCo Pari is working with our young, eager, attractive, energetic and knowledgeable staff.

EDGE: What if I’m a little intimidated by them?

EDGE: What if I’m a little intimidated by them?

KL: You simply need to get past that. Our stylists know what is in, what looks good and what is flattering. You wouldn’t go to a butcher for fish, right? It’s the same when it comes to shopping for fashion.

EDGE: Getting back to shoes for a second, I’m always looking for footwear that makes a statement.

KL: That’s actually the perfect word to define our shoes. Our shoes are not for walking around. Women need to drop the word comfortable when talking about fashionable footwear. You need heels. If women don’t know how to walk in heels they need to learn. You won’t find low, grandmotherly shoes in our stores. Our shoes get noticed.

Some of CoCo Pari’s staff of young fashionistas: (back, l-r) Joy, Aubrey, Stacey, Faith, Lindsey, Briana (manager), (front, l-r) Sophie and Lauren.

EDGE: Looking ahead, when’s the right time to shop for spring vacation?

KL: We start getting our resort wear in January and February, so you should come in then. You can’t go wrong with a pair of sandals and lightweight dresses. We always have a fantastic selection of both on hand.

Editor’s Note: Landau opened her first store at the age of 20. She says she was inspired by “the vibe in Miami Beach’s South Beach district.” CoCo Pari features Christian Louboutin, Jimmy Choo, YSL, Stella McCartney, Alexander McQueen, Herve Leger, Mandalay, Rachel Zoe and Alice&Olivia, among many other top designers. For store locations, hours and more information log onto cocopari.com.

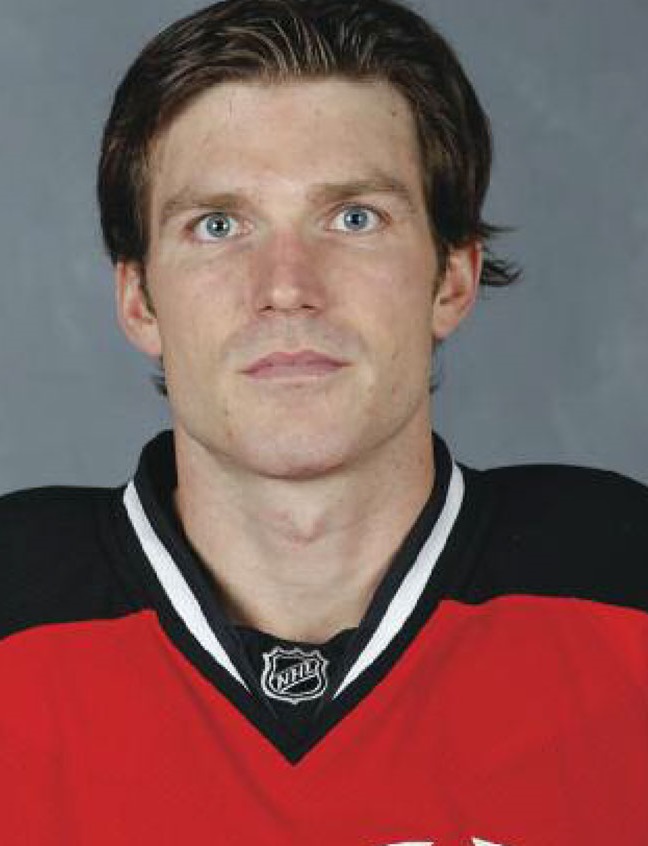

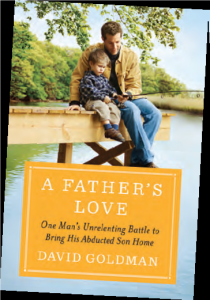

In real life, fairy tales don’t always have happy endings. Young and dashing David Goldman was a model in Milan when he met and married a lovely Brazilian  woman named Bruna Bianchi. Life was good in their Tinton Falls home, especially after the arrival of Sean in 2000. Everything changed four years later, however, after Bruna took Sean on what was supposed to be a brief family visit to Rio di Janeiro. She ended their marriage with a phone call and refused to return, triggering years of agonizing custody litigation in a foreign land. Though her marriage to David was never legally dissolved in the U.S., Bruna married João Paulo Lins e Silva, scion of a powerful family that had provided legal advice to the country’s elite since the 1800s. Bruna and João produced a baby girl (Sean’s halfsister), but Bruna died from childbirth complications. The legal battle only intensified when the family sought to keep Sean in Brazil. In his book A Father’s Love: One Man’s Unrelenting Battle to Bring His Abducted Son Home, David delivers a heart-pounding blow-by-blow of his remarkable battle to win Sean back. EDGE Editor Christine Gibbs welcomed David Goldman into her home this summer, and rediscovered the very human side of a drama that had been played out in newspaper headlines and cable news reports for more than a half-decade.

woman named Bruna Bianchi. Life was good in their Tinton Falls home, especially after the arrival of Sean in 2000. Everything changed four years later, however, after Bruna took Sean on what was supposed to be a brief family visit to Rio di Janeiro. She ended their marriage with a phone call and refused to return, triggering years of agonizing custody litigation in a foreign land. Though her marriage to David was never legally dissolved in the U.S., Bruna married João Paulo Lins e Silva, scion of a powerful family that had provided legal advice to the country’s elite since the 1800s. Bruna and João produced a baby girl (Sean’s halfsister), but Bruna died from childbirth complications. The legal battle only intensified when the family sought to keep Sean in Brazil. In his book A Father’s Love: One Man’s Unrelenting Battle to Bring His Abducted Son Home, David delivers a heart-pounding blow-by-blow of his remarkable battle to win Sean back. EDGE Editor Christine Gibbs welcomed David Goldman into her home this summer, and rediscovered the very human side of a drama that had been played out in newspaper headlines and cable news reports for more than a half-decade.

EDGE: Describe Father’s Day seven years ago.

DG: On Father’s Day 2004, I had just learned that Sean had been abducted by his own mother, my wife, Bruna. Actually, I don’t even want to remember it as Father’s Day that year. That was the first of many holidays that came and went while he was away. I treated each one as if it was just another day. I tried to keep busy and to keep going.

EDGE: Was there a moment when you thought that you might never see your son again?

DG: I never had that moment, and that’s what kept me going. I always believed that we would be together again. However bleak that hope was at times, I never stopped hoping and believing in something that was so true and so right that it would have to happen. It had to happen. I would not give up until it happened.

EDGE: Did the fact that Sean was with his mother and her family give you any comfort?

DG: Well, yes. I knew where he was. I knew that they would take care of him better than if he had been abducted by strangers. Yes, absolutely. But he was mostly with his grandmother, not his mother. In fact his grandmother recently admitted that Sean had lived the whole time with her and not his Mom. I’m still trying to piece things together. It seems that, to some degree, it was Bruna’s mother who was obsessed with our son, and with Bruna’s returning to Brazil. And Bruna could not go back home without her son; what would people think? It was always about image. I wouldn’t say it was exactly “comforting,” but at least I knew that Sean wasn’t someplace that I might never find him.

EDGE: Eventually, you had to deal with Sean’s stepfather— and his wealthy and influential family.

DG: That’s where it became even more concerning. Bruna and I were never even separated in this country—let alone divorced—so I will never consider him as a “stepfather.” This man is a second abductor in my opinion. That family had a sense of entitlement and narcissism that made them feel they were a powerful Goliath in Brazil. So how dare some Gringo, an American fisherman from New Jersey, take them on and drag them through such a mess by fighting against them! Even when I realized how powerful the family was, it didn’t shake me. I don’t know why. Wait, I guess I do know why. I always believed that the rule of law—the rule of God’s law and man’s law—was on our side. I just had to keep standing in the light of truth.

EDGE: It’s almost a cliché that Americans can’t get a square deal when they are fighting in an overseas courtroom. What were some of the frustrations you experienced in your legal battles in Brazil?

DG: According to the terms of the Hague Convention Treaty, an abducted child must be returned within six weeks in order to disrupt the child’s life as little as possible. I immediately approached the Brazilian Central Authority about this, but they refused to file under the Hague Treaty in order to help me as the left-behind parent. After several weeks of no action, I felt forced to hire a Brazilian lawyer, at which time the BCA said that the matter was now out of their hands. Basically the BCA was complicit in the kidnapping.

EDGE: And possibly there was gender bias.

DG: Yes, there was one judge—who wore rock-star sunglasses in court—who stated that she had just lost her own mother and, although she didn’t know the facts of my case, that “the child always belonged with the mother.” She admitted beforehand that that would be her decision and she would back into it somehow. It was ludicrous and offensive. People were even serving coffee to the lawyers and judge right in the courtroom. The lack of decorum throughout my many hearings in Brazilian courts was astounding and so was the attitude and the decisions of some of the judges.

EDGE: Who turned out to be the biggest help to you here in the U.S.?

DG: There were so many people, like my long-time friends Mark DeAngelis and Bob D’Amico, whose support was invaluable. Obviously New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith was just incredible. He went right into battle with me by getting on a plane and flying with me to Brazil. Both of my attorneys dotted every i and crossed every t. They couldn’t control the judges, but they did use the law to our benefit. They closed every door they could and nailed each shut because we were up against some very slick opposition who would slither under any door if they could. Obviously, Senator Frank Lautenberg and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—just coming on TV and speaking about my case— that was unbelievable. Help came from as high up as President Obama. The people from Dateline on NBC and our local New Jersey media pitched in. I couldn’t possibly pick one as being greater than the others. Every bit of help was important. Remember, we eventually got Sean out of there, but only barely by the skin of our teeth.

EDGE: At what point in this almost six-year process did you sense that things might be breaking back your way?

DG: As unfortunate as Bruna’s tragic passing in childbirth was, it gave us—Sean and me—a second chance at life together. It was at that point that not only was Brazil breaking its own law, but also American law and international law. They would have had to change their own constitution regarding custodial rights, since Brazilian law clearly stated that custody was to go to the fit and surviving parent. Once they started breaking their own laws, well, that was when I really and truly believed we could win.

EDGE: Have all the loose ends been tied up, or are there still unresolved issues that require your attention?

DG: Unfortunately they’re not all resolved. The family is still appealing to overturn the decision that returned Sean home to America. They want to have him returned to Brazil, especially his Grandmother. Bruna’s Brazilian “husband” has even sued me on behalf of Sean’s half-sister Chiara. They’ve opened up lawsuits in both countries. Although Sean’s Brazilian grandparents have claimed all they ever wanted was to be allowed to visit, what they were really after was shared custody. They continued to refuse to acknowledge that this was Sean’s home and that, as his Dad, they should support me. While with them in Brazil, he wasn’t even allowed to call me Dad or to hug me when they finally let him see me. Fortunately, Brazil has now made parental alienation a crime. Ironically, Bruna’s Brazilian “father-in-law” was actually lecturing on how a child can be turned into an attack missile against the left-behind parent—even while that family was guilty of doing exactly that!

EDGE: How would you assess the performance of your legal team, the Brazilian media and the Brazilian public?

DG: I’d have to give both my lawyers outstanding grades for their due diligence, their knowledge of the law, and their teamwork. Patricia Apy, my American counsel, is brilliant in this field. Her legal expertise and determination to advocate for her client is amazing. And Ricardo Zamariol, at the age of 23 or 24, faced off with some powerful opponents in Brazil. The Brazilian media were very, very biased. They tried to make it into a nationalism issue by supporting the kidnappers. Much of the truth finally did come out, but it was amazing how distorted the reporting was. Apparently, the families had some close connections with some of the big media networks. The Brazilian public, in the beginning, was inundated with slander and lies, but once the truth started getting through, the public identified with me as victim even though I was an American. Many of them had been personally victimized by the privileged and powerful in high society. They finally realized that I was one of them. They recognized the miscarriage of justice when they finally could see it. They knew how wrong it was to separate a parent from his child, especially when I was the only surviving parent.

EDGE: What do you hope Sean comes away with out of all of this?

DG: I hope, first of all, that he can grow up in a normal and loving environment as any parent would—that he hasn’t been too scarred by underlying issues. He’s been through way too much already. Losing his Mom had to be tremendously painful, especially at age 7. I want my child to grow up to be thoughtful, caring, considerate, enlightened…but all in good time. Right now my focus is for Sean to be an 11-year-old boy doing ordinary things—going to camp, playing ball, joining a swim team, going to the Sandy Hook beach. I want to instill in Sean good values— honesty, humility, gratefulness, and sincerity. The exact opposite of the values he was taught while in Brazil.

EDGE: What lessons will you carry with you going forward?

DG: To never give up hope, especially when you know that what you’re doing is so right. You have to keep going. You have to keep carrying that torch of hope forward. In all cases like mine, the suffering is not on the part of the parent alone. It’s shared by everyone who is close to the abducted child. So I want to continue to carry that torch—through our Bring Sean Home Foundation—to make change for the better really happen for others like Sean and me.

EDGE: What has been the easiest part of the transition back to life with Sean?

DG: Just doing routine, mundane things together at home, like sitting down and watching TV or playing a video game, playing catch, doing homework.

EDGE: What have you found to be the most challenging?

DG: Some of the most challenging part comes from certain learned behavioral traits that Sean picked up while he was in Brazil, such as avoiding accepting responsibility. Most kids will make some excuses at one time or another, but Sean sometimes takes it to a level well beyond his years. It’s just too mature. So I spend a lot of time trying to determine what is normal for an 11-year-old and, what is a byproduct of Sean’s special situation—which included a good deal of brainwashing. The picture they painted of me, of New Jersey, of America, was obviously not true. When he came home, he saw reality—so much love, so much patience, so much understanding from me, from his grandparents, from the community. Having been told horrible lies for five long years, the reality was shocking.

EDGE: In your book you also talk about the challenge of setting parameters. How does that apply to Sean?

DG: Sean had lived an adult lifestyle with his grandparents— staying up late, getting up late, going out socially with adults, and so on. I have been working on getting him back to being a child again.

EDGE: And how is that going?

DG: Once Sean opened that curtain to his childhood, he just wanted to go right back to being a kid again. He’s learning to let go of the adult behavior and mannerisms. He wants to be a kid as much as I want to be his Dad.

EDGE: How did you celebrate this past Father‘s Day?

DG: We went out on our boat along with Sean’s Pop-Pop, who has said to me that not only did he get his grandson back, but he got his son back, too. Now that Sean is back, every day is Father’s Day for me.

Editor’s Note: David Goldman has testified before Congress and is continuing his effort to eliminate child abduction injustices around the globe. For anyone  facing the ordeal of an abducted child, bringseanhome.org offers support, advocacy options, and a summary of ongoing legal activity in this field. A Father’s Love: One Man’s Unrelenting Battle to Bring His Abducted Son Home (Viking $26.95) was released this past spring.

facing the ordeal of an abducted child, bringseanhome.org offers support, advocacy options, and a summary of ongoing legal activity in this field. A Father’s Love: One Man’s Unrelenting Battle to Bring His Abducted Son Home (Viking $26.95) was released this past spring.

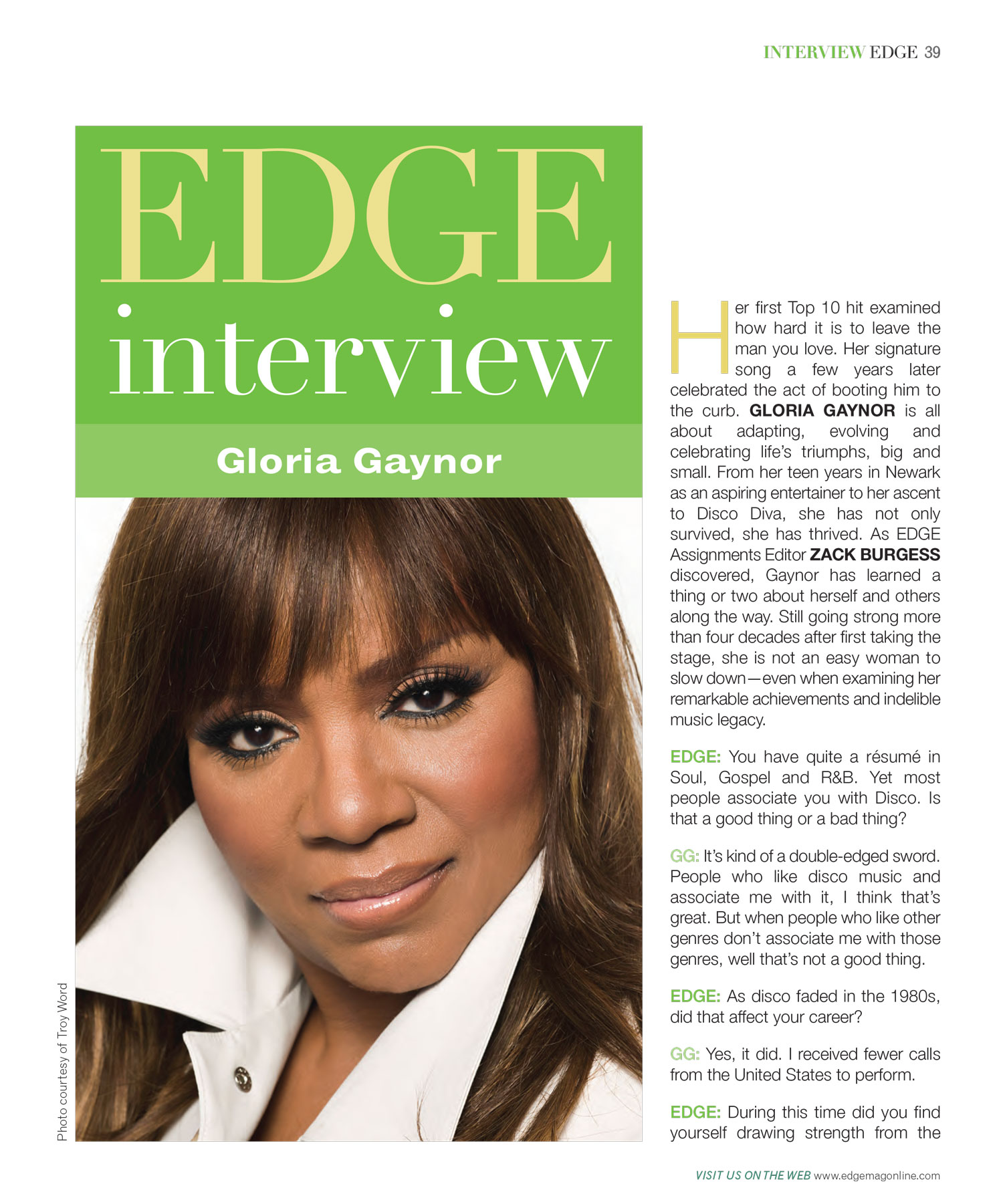

Some athletes seem destined for stardom before they reach their teens. Others blossom in adolescence or soon after. And then there are those fascinating few whom stardom kind of “creeps up on”—taking them, their fans, their friends and family, and even their sport, largely by surprise. David Clarkson is okay with being one of those athletes. The high-scoring star of the Devils was a major reason why they made it all the way to the Stanley Cup Finals last spring, yet it wasn’t too long ago that he was undrafted and ignored by all 30 professional hockey teams. That kind of career arc tends to ground a guy in reality. It also enables him to savor the sweetness of success. EDGE Editor Mark Stewart grabbed Clarkson after a recent practice at the Prudential Center and talked about the Toronto native’s design for living. Turns out it hasn’t changed much since he was scrapping for a spot on an NHL roster. Clarkson takes it one day at a time, finding subtle ways to improve, enjoying life’s little pleasures and appreciating every new day.

Photo credit: Bruce Lowe

EDGE: Consistency is such an important part of an athlete’s life. Not just on the ice after the puck drops, but before you even get to the rink. What are some of the things you do on game day that keep you in a consistent rhythm?

JC: I’d say that I’m pretty superstitious. For the past five years, I’ve stopped at Starbucks on the way to every single home game. It’s part of my routine. I get my sticks ready at a certain time, I get a massage at a certain time. There are a lot of little things I do to prepare. I think it helps me relax and keep my mind off of details that aren’t related to the game. It’s also that, as you said, athletes are very routine-oriented people. When things are going well, a lot of us tend to do things like eat the same meal the night before games. If it worked once, why change?In terms of routine, on game day we usually have a morning skate, then I’ll go back home to West Orange and see my two-year-old daughter McKinnley for a little bit, take a nap after lunch, and head out to the game.

EDGE: What’s the meal you ask for at home when you’re in a groove?

DC: My wife, Brittney is a great cook and baker. I’m very lucky in that department. She makes this chicken with capers in an amazing sauce. I love that.

EDGE: What about when the Devils are on the road? Do you look for the same things on the menu, or do you experiment with local specialties?

DC: I might try something different for an appetizer, but I like to stick to the same entrées before games. Steak, for sure. And sometimes I’ll see what kind of fish is on the menu.

EDGE: What do you watch on TV?

DC: I grew up a huge Seinfeld fan. That’s one of my favorites. Lately I’ve become a big fan of Dexter and Homeland. And How I Met Your Mother.

EDGE: What’s on your iPod?

DC: Every kind of music. My dad was born in Scotland and my mom is Irish, so I have a lot of Rod Stewart on there. But a very wide range of artists, I’d have to say. I love music.

EDGE: Was it weird not playing hockey this fall?

DC: It was. Still, you try to make a positive when something bad happens. So I used that time to train more and get stronger. And I ended up going over to Austria and playing for a little bit. But you know, after the run we had to the Stanley Cup Finals last spring, we were all pretty banged up and tired. I liked being able to relax and see my daughter grow up. We travel a lot as athletes, so that time I got to spend with my wife and daughter was special. By the end, though, I think Brittney was sick of me being at home. She was looking at the calendar wondering when I’d be getting back to work.

EDGE: A lot of our readers send their kids to hockey camp. What is David Clarkson’s great hockey camp story?

DC: I went to Brendan Shanahan’s hockey school as a kid. He was someone who played the game hard, and at the end of each camp they would hand out a stick for the player who’d worked the hardest. I got it one year—my dad still has that stick! But I was like any kid at a camp, dreaming about being here in an NHL locker room one day. I never thought I’d make it, of course, so it was pretty special just to be around those guys at that time in my life.

Photo credit: Bruce Lowe

EDGE: You’d been on the Devils roster a couple of seasons when Shanahan joined the club in 2009 at the age of 40. Did he remember you as a camper?

DC: No. I had to show him pictures of me at the camp—when I was really, really little. He told me if I ever showed anyone else those pictures I’d be in trouble!

EDGE: This is your second time playing for the Devils’ coach, Peter DeBoer. Besides the fact you’re both older and wiser, has anything changed in a decade?

DC: No, he’s always coached the same, structured hockey. If you stick to his system, to what he’s preaching, you’ll be successful. I won a Memorial Cup with him in 2003 in Juniors and last year we went to the finals. So I think what he does with a team shows in the results. Where he goes, success follows.

EDGE: You’re one of the few stars in the NHL that went overlooked in the draft. How did the Devils discover you?

DC: Pete had a lot to do with it. I was 20, 21 years old and no one had drafted me. I didn’t know what was going to happen next. I had been to a couple of tryouts that Pete had arranged, but no one was really sure if I was good enough or tough enough. I think that pushed me harder to prove myself. I played one more year for him, and then the Devils and a couple of other teams called, and the Devils saw something and signed me. It just goes to show, it pays to work hard and do the little things well.

EDGE: What changed in your game to make you a goal-scorer last year, and even more so this year? Is that work you do in-season or during the off-season?

DC: It’s a very wide range of things. As an athlete you can never be happy with where you are. You always try to get better. Having a coach who put me in situations where I had to produce helped me, too. Pete believed in me. But I think in the summer, you have to go home, figure out what you want to get better at, and really work on it.

EDGE: When you say “work on it” does that mean work on the ice, in the weight room? Does that work happen between the ears? Where does that kind of transformational work have to take place?

DC: A lot of it is in your head, yes. But I’ve also hired people to help me with my skating and my hands over the summer. There’s a lot of training and a lot of pushing. I believe the day you are happy with where you are, that’s the day it starts going in the other direction. That’s something I’ve learned from the guys I’ve been lucky enough to play with in this organization.

EDGE: Whenever you’re on the ice, there’s definitely a buzz in the Prudential Center—not just when you’ve got the puck, but when you deliver a check or just get in a guy’s grill. Do you feed off that energy or are you oblivious to it?

DC: Oh, I feed off it. We are very lucky as Devils to have the type of fans we do. I don’t think we could have done what we did last year otherwise. When they start cheering, we get a real charge out on the ice. You really do feel that electricity from the fans.

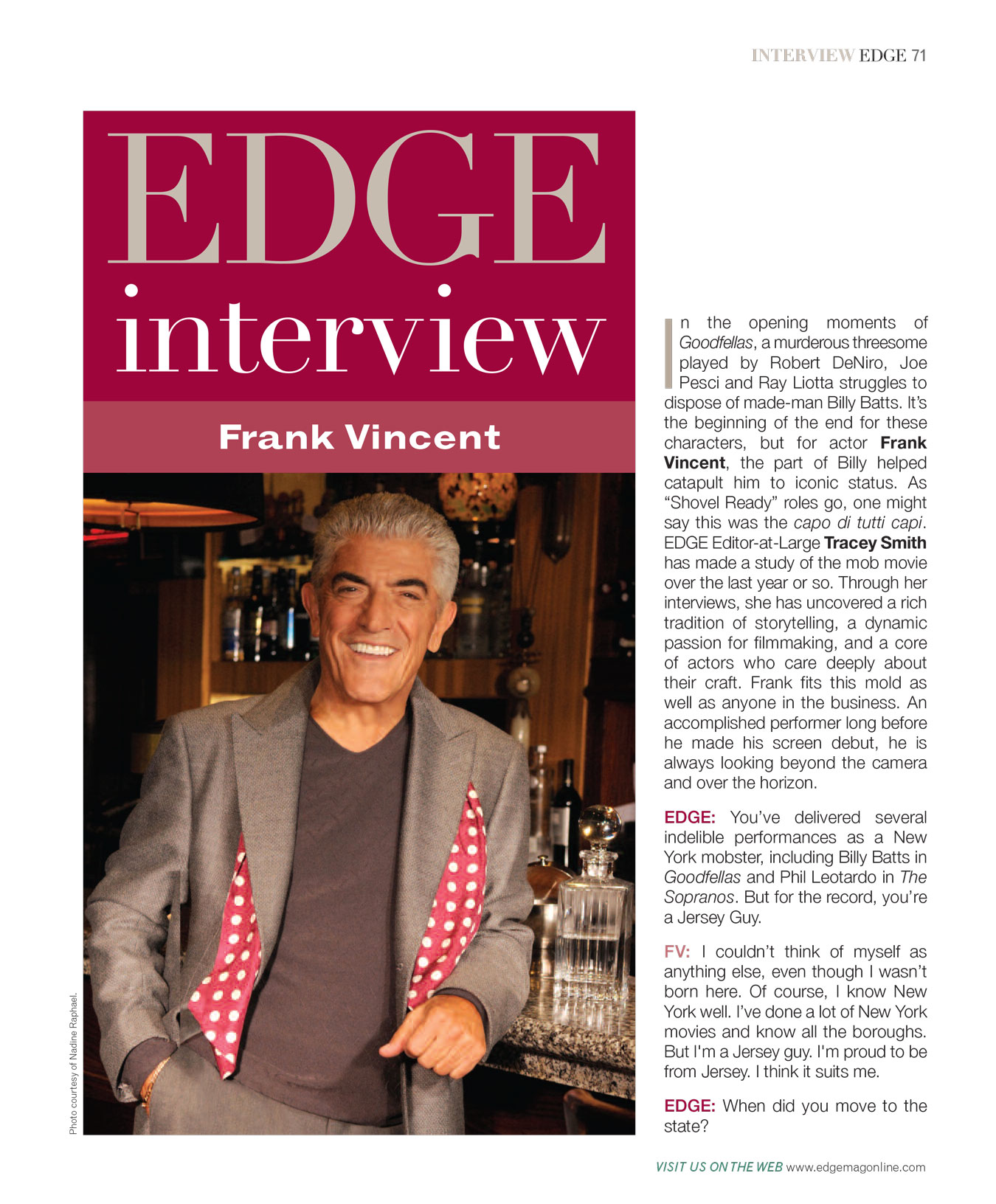

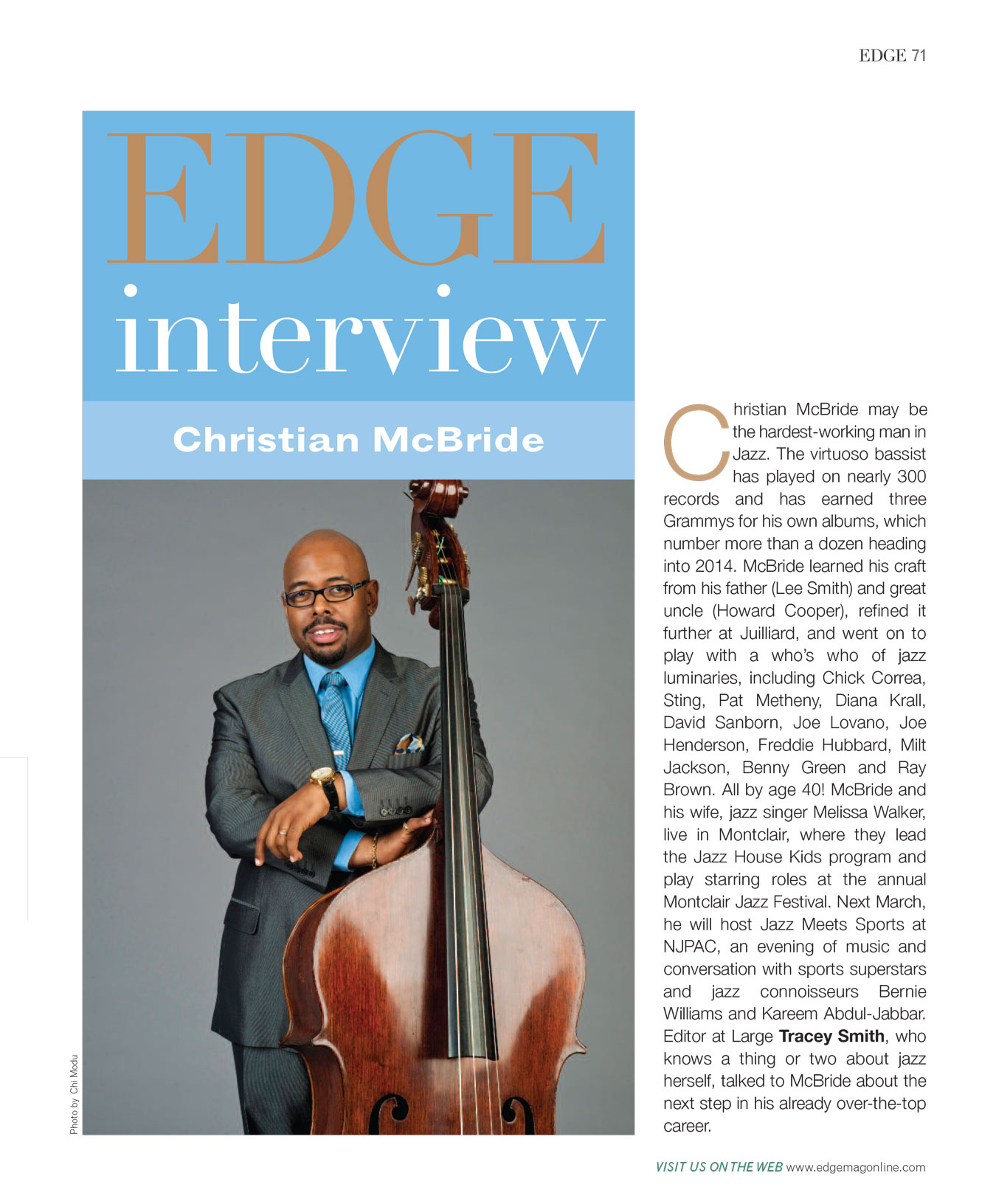

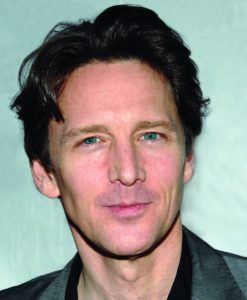

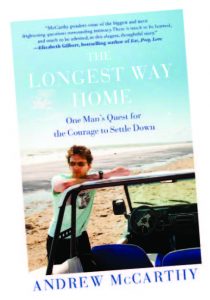

Who knew? Behind the gentle, sensitive blue-eyed preppy we all took Andrew McCarthy to be, there beat the heart of an introspective adventurer and master storyteller? In his second life as a globetrotting journalist, McCarthy has contributed to National Geographic Traveler, Travel+Leisure, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times. He also authored The Longest Way Home: One Man’s Quest for the Courage to Settle Down. EDGE Editor at Large Tracey Smith set out to determine when, why and how this Garden Stater transitioned from beloved actor to best-selling writer. As she discovered, these are merely two facets of the same glittering artist.

EDGE: It takes a tough skin to be an actor and to be able to put yourself out there, in front of people. When you look back at your career what enables you to do both?

AM: I don’t know if it takes a tough skin, but to have one it helps. Most people who go into acting probably don’t have one. I guess you develop one over time—

Photo courtesy of Free Press

or you just get beaten up enough and grow immune. I cannot imagine what else I would do, I’m not qualified to do anything but act. When I was a kid and discovered acting, I was 16, in high school. I was in my first play, and I had an amazing experience. I felt at home with myself, like I had never felt before, and the decision was made in that instant that there was no decision to make. It was just something I was going to do.

EDGE: Did writing hold the same kind of appeal?

AM: It was a similar feeling of relief, a feeling of being at home with myself. I have been lucky to say that my passions have become my jobs, which is a good thing—and I don’t know any way else to do it.

EDGE: Your travel writing tends to take you to the ends of the earth. Is that something you’ve done consciously?

AM: I find remote destinations interesting. I’m looking to be placed outside my comfort zone. I live in the city, so I like going to the Sahara Desert or Patagonia. Those kinds of extreme places really get my attention and wake me up in a way. It’s important to travel the world. It’s sort of a responsibility to see and experience as much of the world as we can. It makes us better people and more responsible global citizens, as it were. And also I find it’s fun as hell, too! I have a globe in my house and sometimes I just sit and sort of spin it. When I find a spot I don’t know about, often that’s reason enough for me to just get on a plane and go.

EDGE: Do you feel like a different person when you return from one of these adventures?

AM: Paul Theroux said, “You go away for a long time and return a different person…you never come all the way back.” In a certain respect that’s true. I’m an accumulation of whatever has happened to me—whether I am on the road or whether I am home. I find I am a better version of myself when I’m on the road. I’m more interested, I’m more curious, more open, braver, more engaged, more right-sized. When you get home it actually seems as if the effects wear off instantaneously. But the real changes, the deeper changes, go much deeper than that. They’re much more substantial.

EDGE: Is your family fully behind your new career?

AM: They are pretty aware that it’s the thing for me to do. Some people like to go to the gym. I like to go to Ethiopia (laughs).

Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

EDGE: Has your travel writing fine-tuned your acting in any way?

AM: On a human level, it’s made me more relaxed in the world, and the more relaxed you are as an actor the better you are as an actor. Laurence Olivier said the key to acting is relaxation. So travel has opened me to be more relaxed in myself and how I deal with the world. And it’s helped my observational skills, which is what acting is all about. I think it makes me more awake and alive. And whenever you’re more awake you’re a better actor.

EDGE: I’m guessing a lot of your fans are anxious to know whether you are close with any of the actors you worked with in your “Brat Pack” days.

AM: I don’t keep in active touch with any of them. That’s the power of movies, you know, just to freeze a moment of time. We were so public at that time. People took a snapshot of us and they hold on to that snapshot. Everyone evolves from their 20’s to when they’re in their 40’s, so hopefully we are all evolving. When I look at these people from afar, I see them doing all sorts of interesting things with their careers. For instance, Emilio Estevez has gone on to direct some very interesting movies. The Way [co-starring his father, Martin Sheen] was just a very lovely movie.

EDGE: When you look into your crystal ball, what do you see five years from now? Do you want to be a playwright?Write a biography?

AM: Write a biography about someone else? No, I don’t see myself ever doing that. I do have a novel that I have been finishing and also an idea for another non-fiction book. Things just seem to have a natural evolution as they present themselves, so I try to pay attention and follow that. I’ve never been one of those people who has a good five-year plan. Whenever I do, it gets completely derailed.

EDGE: Mark Twain maintained that, 20 years from now, you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. “So throw off the bowlines, sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.” Would you agree?

AM: Yeah, I think that’s very true. And that’s the thing that travel does, it obliterates fear. It did in my life. I think that’s 95 percent of what Twain is talking about. Fear is not a viable thing to dictate our behavior. It does too often. It’s a wet blanket. Fear complicates your success. And it masquerades as many things. The challenge is identifying fear, whatever that fear may be. EDGE

Editor’s Note: The Longest Way Home (2012, Free Press) will be available in paperback this spring. In its review of the book, The New York Times described it as “a good book about a good man who’s trying good and hard to figure himself out.” Andrew grew up in Westfield and Bernardsville. He lives in New York City with his wife and daughter.