Happy holidays in Japan & Taiwan

By Sarah Rossbach

Wherever I travel, I cherish that feeling of being transported in time and place to experience a historic site as the ancients did. When in Versailles, I imagine Marie Antoinette is frolicking as a milkmaid in her hameau. In London, I picture Sir John Soanes at his desk gazing at a roman plinth as he designs the Bank of England. In Kyoto garden, I envision the fictional Prince Genji courting Lady Murasaki with a clever cherry-blossom-inspired haiku. Which is why I am so utterly irritated by the busloads of selfie-stick-toting tourists who interrupt my carefully curated daydreams. My solution? Travel during Christmas

And not to Aspen, Park City, Gstaad, St. Moritz, Hawaii, the Caribbean or other traditional winter holiday destinations. This past December, we took our family vacation in Japan and Taiwan, two fascinating countries that can be completely booked-up during the height of their tourist seasons. Japan, for example, is impossible during its more temperate fall—with the brilliant colors for autumn leaf-watchers—and in spring, too, when it’s overrun with tourists elbowing their way between the plum and cherry tree blossoms. At many of the popular historic sites in Taiwan, visitors find themselves unable to secure tour reservations during the high seasons. These situations are unlikely to change. Right now, the US dollar enjoys a favorable exchange rate with both the Japanese yen and the new Taiwan dollar; taxis and mass transit are 50% less expensive than in the West, making both countries vastly more affordable than, say, England or France

Eschewing the yearly wrestling match with the Christmas tree, the added pounds from holiday parties and the challenge to find that perfect present for each and every member of the family, my husband and I boarded a flight with our son to Tokyo a week before Christmas. The planning for this trip began when our daughter, who is teaching English in Taiwan for a year, announced that she would not have the opportunity to return to New Jersey for the holidays

Flying halfway around the world isn’t an easy endeavor. Having done so on a number of occasions, there are some rules I try to follow. If you can save up your airline points, try to upgrade to an economy-plus or, even better, a business class seat. Also, try to arrive in the late afternoon so you can go to bed early and get on a local sleep schedule. Pre-purchase a Japan Rail Pass in the US so that, when you arrive at Narita Airport, you only have to pick up your tickets to the hour-long direct train ride to Tokyo. Before any train trip, we pre-booked our assigned seats at Tokyo Station.

All photos by Sarah Rossbach

TOKYO IN 36 HOURS

Our stay in Japan’s largest city was meant to be short, less than two days. We chose the Palace Hotel, located in the middle of the city (a convenient 10-minute walk from Tokyo Train Station) and overlooking the Emperor’s 1.3 square mile park-like estate. This neighborhood, known as Marunouchi, is Tokyo’s financial district, so it’s quieter and less busy during the weekend and in the evenings. As a result, it was easy to book a table for dinner near our hotel. In much of modern Tokyo, restaurants are not at street level; thanks to the guidance of our hotel’s concierge, we enjoyed amazing sushi on the 35th floor, steaming ramen on the 6th floor and $10 soba on the 7th floor of various local office/vertical shopping mall buildings. Of course, western restaurants exist. Yet the food loses something in translation. Case in point was brunch the next day at my favorite French bakery chain, Maison Kaiser. There were only three weird choices: beef mushroom soup, sliced beef or beef in a chef’s salad

Our time being short, we hired a guide for the afternoon to take us on a Tokyo version of speed-dating. Our guide, Mariko Okunishi, directed us through the city’s excellent (and clean!) subway system to the Meiji Shrine, Neju Museum and Garden, Harajuku Street—a young people’s area where women dressed like little western girls (which I really didn’t need to see)—Shibuya Crossing, the busiest crossroad in the world, and the Ginza aka Tokyo’s Fifth Avenue. The constraints of time and jet-lag prevented us from visiting the 7th century Asakusa Buddhist Temple and various museums devoted to bonsai, Japanese woodcuts and our son’s passion, Anime

The 95-year-old Meiji Shrine is dedicated to the Meiji Emperor and Empress and embodies the traditional Shinto worship of nature. It is a living monument, as locals celebrate weddings and children’s “coming of age” celebrations at 30 days, three, five and seven years. At the entrance to the park are troughs of water and ladles to clean and purify yourself (i.e. wash your hands). The shrine and its 170-acre park was the highlight of our day.

AH, KYOTO

AH, KYOTO

Kyoto is a two-and-a-half-hour ride on a super-clean bullet train from Tokyo. We were smart and arrived early at the station to get the lay of the land; we had to query a handful of uniformed workers before locating our platform. We knew to request a seat on the right side of the train in order to catch a glimpse of Mt. Fuji. While Tokyo has been Japan’s capital since 1868, Kyoto was the seat of power in Japan for over 1,000 years and, as such, offers a stunning breadth and depth of historical and cultural sites. Whenever Kyoto is mentioned, the Japanese sigh and say, “Ah Kyoto”—no doubt invoked by romantic images of parasol-toting Geishas strolling by cherry blossoms in spring and vibrant red Japanese maple leaves in autumn

That being said, as we stepped off the train, I was struck by how much Kyoto, like Tokyo and New York, is a modern city. Japanese sensibility still can be found at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, as well as gardens, preserved palaces and museums. Kyoto boasts over 2,000 temples and shrines, ranging from ones designated as World Heritage Sites to mini sidewalk altars. To immerse ourselves further in Kyoto’s culture, we splurged a bit and stayed at a ryokan, a traditional Japanese inn, where guests sleep on futons in tatami rooms and dine on nine-course kaiseki meals for dinner and breakfast, presented by uber-polite kimono-clad servers. While the quality of these inns can vary, our stay at the Yoshikawa Inn was very comfortable, warm and dry on a cold and rainy day. It was a highlight of our five days in Japan.

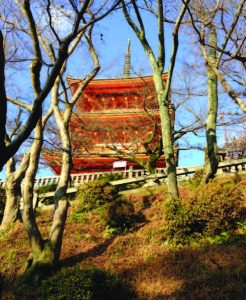

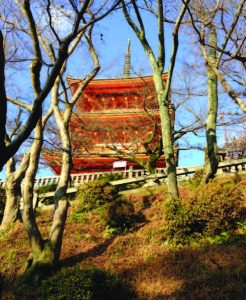

Though lighter in December, tourism at Kyoto’s top attractions is a year-round business. To beat the Chinese tourist buses, we rose early and visited the Kinkaku-ji Golden Temple (page 13), a very gold Buddhist temple. In concept, it dates back to 1398. But in fact it is a 1950s replica of the original, which was burned by a deranged monk. Another wonderful site is the Kiyomizu-dera Temple (left), founded in 778 and built in the 17th century with joinery (no nails) on a hillside overlooking Kyoto. While it is a Buddhist temple, Shinto shrines dot the grounds to “protect” the wooden temple from fire. Visitors often seek blessings and good fortune; they can drink from a spring-fed waterfall that is said to have wish-granting powers, leave petitions to the gods, or purchase good luck talismans. A former practice (fueled by the belief that anyone who survived a 13-foot jump from the temple veranda would have wishes fulfilled) wisely is prohibited now.

Though lighter in December, tourism at Kyoto’s top attractions is a year-round business. To beat the Chinese tourist buses, we rose early and visited the Kinkaku-ji Golden Temple (page 13), a very gold Buddhist temple. In concept, it dates back to 1398. But in fact it is a 1950s replica of the original, which was burned by a deranged monk. Another wonderful site is the Kiyomizu-dera Temple (left), founded in 778 and built in the 17th century with joinery (no nails) on a hillside overlooking Kyoto. While it is a Buddhist temple, Shinto shrines dot the grounds to “protect” the wooden temple from fire. Visitors often seek blessings and good fortune; they can drink from a spring-fed waterfall that is said to have wish-granting powers, leave petitions to the gods, or purchase good luck talismans. A former practice (fueled by the belief that anyone who survived a 13-foot jump from the temple veranda would have wishes fulfilled) wisely is prohibited now.

Surrounded by two moats, the Nijo Castle, the former Shogun’s home, is definitely worth a visit. The castle floors were built to squeak on purpose—as an early form of burglar alarm called “nightingales”—alerting the Shogun of assassins. The 400-year-old Nishiki market is also a fun typical Japanese destination. Its neat, colorful stalls selling everything from matcha to mocha (tea to rice cakes), sushi to sake, and pickles to dried fish. If you enjoy gardens, take a trolley to the Arashiyama area to visit Tenryu-ji, a Zen Temple with a tunnel-like bamboo grove leading to Okochi Villa, a beautiful garden designed by film star Denjiro Okochi. Across the river is a park full of wild but people-friendly monkeys.

Unfortunately, we did not make it to Nara, the capital city of the neighboring prefecture to Kyoto. It boasts some of the best examples of Tang Dynasty Chinese (yes, Chinese!) temple architecture. However, our next stop, Taiwan—a four-hour plane ride from Tokyo—would offer many outstanding examples of Chinese dynastic art and architecture.

ON TO TAIWAN

ON TO TAIWAN

The island nation of Taiwan, home to 23 million people, was known for centuries to the west as Formosa, or beautiful island in Portuguese, a name bestowed upon it by 16th century sailors. In the ensuing years, Taiwan’s indigenous people were pushed to the margins by Han Chinese, who now make up more than 95 percent of the population. In 1949, Chiang Kai-shek fled to Taiwan after losing a civil war on mainland China to Mao’s Communist forces. The island has been known officially as the Republic of China ever since. While increasingly proud of its native Taiwanese culture, Taiwan offers fantastic Chinese food, temples and works of art—some would say the best in the world. Taipei, Taiwan’s capital, has emerged as one of the most vibrant cities in Asia. It is clean, relatively safe, has reliable and inexpensive transportation, great food and a vibrant nightlife. The Taiwanese demeanor strikes me as a pleasant, modern mixture of traditional Chinese and Japanese politeness. And because Taiwan is still perceived by much of the world as an electronics producing nation, it refreshingly isn’t on everyone’s tourist destination list. Yet

We arrived in Taipei on Christmas and, happy to forego our traditional heavy Christmas dinner, we dined at James Kitchen, an informal and quirky Taiwanese restaurant a local friend had recommended. Our taxi dropped us off on winding Yongkang Street, which is lined with hip shops and restaurants, and we entered a narrow building cramped with diners. The owner led us past the kitchen, up rickety steps to a tatami room, with customers’ drawings covering every inch of the walls and ceilings so low I couldn’t stand up. Seated on cushions at our low table, we enjoyed mushroom dumplings, pork lard rice, sautéed vegetables and the fish that James Kitchen is known for. Our check was about $15 per person

We arrived in Taipei on Christmas and, happy to forego our traditional heavy Christmas dinner, we dined at James Kitchen, an informal and quirky Taiwanese restaurant a local friend had recommended. Our taxi dropped us off on winding Yongkang Street, which is lined with hip shops and restaurants, and we entered a narrow building cramped with diners. The owner led us past the kitchen, up rickety steps to a tatami room, with customers’ drawings covering every inch of the walls and ceilings so low I couldn’t stand up. Seated on cushions at our low table, we enjoyed mushroom dumplings, pork lard rice, sautéed vegetables and the fish that James Kitchen is known for. Our check was about $15 per person

Much of Taipei is very modern but, as we had in Japan, we sought out the traditional and cultural. One of our first stops was the Lungshan Temple (above). Originally built in 1738, the temple still serves as a local Buddhist center where people come to pray. Along the alley leading to the temple, we entered a simple vegetarian noodle stall, favored by monks, to enjoy soup noodles and dumplings for about $3 per person

If you are adventurous and don’t mind street food and street ambiance, you can get delicious, healthy food fast and cheap. For instance, at a stall near a university, bowls of perfectly prepared cold sesame noodles topped with shredded cucumber came to $1 per person. Even at the wonderful and popular Taiwanese dumpling chain Din Tai Fung, the check for beer and more than enough steamed soup buns and dumplings to fill five adults totaled $60. The bill for a yummy hotpot dinner of fresh vegetables and sliced beef was about $15 a head. Taiwan also has expensive and upscale restaurants. Some can be found in department stores and hotels, including our hotel, Le Meridian. So after enjoying wonderful inexpensive meals, I treated our family to Cantonese food at My Humble House. Its name is something of a deception, as nothing at the restaurant—from the food to the décor—is humble. Delicious, yes. Humble, no. The service was swift and professional and I am still dreaming of the shrimp dim sum and the barbecued pork, buttery moist pork with a crispy skin—sort of a yin-yang of textures. While you can splurge on expensive eight-course meals, our bill for an a la carte dinner at this top restaurant came to a reasonable $135 for four people.

To get a sense of Taiwanese culture, a friend who lives locally took us to Di Hua Street, the oldest street in Taipei, to view shops selling tea, ceramics, fabric and Chinese medicine. With a few structures dating back to the era of Dutch rule in the mid-1600s, much of the historic architecture has been restored without displacing local businesses. We spent the afternoon wandering through a traditional Taiwanese district with narrow streets, local shoppers and 19th century buildings still in the hands of the original families

If Taipei is your only stop in Taiwan, you still can enjoy scenery and hiking, be it in the city’s vast botanical garden, a steep climb up Elephant Mountain, or a trek up the more challenging Yang Ming Mountain. A bit further away (daytrip distance) is Taroko Gorge, with its hiking trails and rope bridges, Yilan’s hot springs, and beautiful Sun Moon Lake

To my mind, the most compelling reason to visit Taipei is to view the world’s finest collection of Chinese art at the National Palace Museum just north of the city. How did these treasures land in Taiwan? When Chiang Kai-shek made his speedy exit from China, he and his KMT (Kuomingtang) troops had time to cart away crates of nearly 700,000 exceptional works of art formerly owned by millennia of emperors. Here the peerless imperial treasures—jades, Neolithic bronzes, porcelains, painting and calligraphy scrolls, jeweled mystery boxes—are exhibited with clear explanations in Chinese, Japanese and English. With exhibits rotating several times in a year, it would take over 30 years to display the entire collection. On our visit, we saw rare jade carvings, fine Song Dynasty celadon porcelains and stunning bird, animal and flower paintings by Giuseppe Castiglione—an 18th century Jesuit priest who began his stay in China as an Italian missionary. Castiglione became a trusted Imperial court painter who also created portraits of the Empress and Emperor during the height of the Qing Dynasty

To my mind, the most compelling reason to visit Taipei is to view the world’s finest collection of Chinese art at the National Palace Museum just north of the city. How did these treasures land in Taiwan? When Chiang Kai-shek made his speedy exit from China, he and his KMT (Kuomingtang) troops had time to cart away crates of nearly 700,000 exceptional works of art formerly owned by millennia of emperors. Here the peerless imperial treasures—jades, Neolithic bronzes, porcelains, painting and calligraphy scrolls, jeweled mystery boxes—are exhibited with clear explanations in Chinese, Japanese and English. With exhibits rotating several times in a year, it would take over 30 years to display the entire collection. On our visit, we saw rare jade carvings, fine Song Dynasty celadon porcelains and stunning bird, animal and flower paintings by Giuseppe Castiglione—an 18th century Jesuit priest who began his stay in China as an Italian missionary. Castiglione became a trusted Imperial court painter who also created portraits of the Empress and Emperor during the height of the Qing Dynasty

As a student studying Chinese in Taiwan, the National Palace Museum was my favorite destination and it was as quiet as a library. Today, busloads of Chinese and Korean visitors crowd exhibits. The locals typically wait until Friday and Saturday evenings, when the crowds disappear and they can visit the museum free

The ancient Chinese have a proverb: “Walking 10,000 miles is better than reading 10,000 books.” When visiting any foreign country, we learn a great deal experiencing firsthand its scenery, sites, food and people. During our five-day stay in Taiwan, I noticed something that I had been blind to when I lived there as a student many decades ago. I was struck by how polite, kind and helpful local strangers were to us and to each other. Whether at Christmas or anytime of the year (except hot, humid typhoon months of July and August) visiting Taiwan is a lovely experience

The ancient Chinese have a proverb: “Walking 10,000 miles is better than reading 10,000 books.” When visiting any foreign country, we learn a great deal experiencing firsthand its scenery, sites, food and people. During our five-day stay in Taiwan, I noticed something that I had been blind to when I lived there as a student many decades ago. I was struck by how polite, kind and helpful local strangers were to us and to each other. Whether at Christmas or anytime of the year (except hot, humid typhoon months of July and August) visiting Taiwan is a lovely experience

GEISHAS, GEISHAS EVERYWHERE

GEISHAS, GEISHAS EVERYWHERE

Alas, few of them are real…or even speak Japanese. Kyoto’s Geisha costume stores and rental shops do brisk business by the busload with young Chinese women, who mince along the winding temple paths or through the narrow streets of the historic Geisha districts. After weaving through scores of ersatz Geisha girls, we finally bumped into the “real deal,” along with her retinue, in the Gion district, best known as a filming location in the movie Memoirs of a Geisha.

The last week in January is a particularly popular time to visit Key West, especially for sun-worshipping foodies. That’s when the sleepy town perks up for the Key West Food & Wine Festival, which just completed its sixth spin around the block (the block being Duval Street, main drag of the Conch Republic). The brainchild of local legend Marc Certonio (left), the Wednesday-thru-Sunday gathering is, happily, still something of a well-kept secret. There are more than 30 different events, including various strolls, tastings and beach parties—but with dozens, not a mob of hundreds. Also, Certonio has cultivated strong relationships with wine purveyors and wine makers, so you’re likely to see wines of small production and hard-to-find beauties. This year, Archery Summit, Foxen and Byron wines were being poured.

The last week in January is a particularly popular time to visit Key West, especially for sun-worshipping foodies. That’s when the sleepy town perks up for the Key West Food & Wine Festival, which just completed its sixth spin around the block (the block being Duval Street, main drag of the Conch Republic). The brainchild of local legend Marc Certonio (left), the Wednesday-thru-Sunday gathering is, happily, still something of a well-kept secret. There are more than 30 different events, including various strolls, tastings and beach parties—but with dozens, not a mob of hundreds. Also, Certonio has cultivated strong relationships with wine purveyors and wine makers, so you’re likely to see wines of small production and hard-to-find beauties. This year, Archery Summit, Foxen and Byron wines were being poured.

WEDNESDAY

WEDNESDAY THURSDAY

THURSDAY FRIDAY

FRIDAY

On Marc Certonio’s advice, we snagged a pair of tickets to the event at Charlie Mac’s, a local spot that has some of the best food in town. Juan Hernandez (right), the southeastern director for Domaine Select wines, was conducting a six-course, six-wine dinner for 30 people. I don’t even know where to begin, but suffice it to say that when the braised pork and pasta dish came out paired with a semi-dry Lambrusco, my eyes rolled back into my head. That was course four or five. At some point, Juan decided that seven courses was better than six; either that, or I just lost track. Chef Michael Schultz was the man behind the culinary madness. He is the chef for Pat Croce’s various restaurants and establishments in Key West and he has an unbelievable talent for all things fish. If you do one thing when you come down to Key West, eat at one of Chef Mike’s establishments (my favorite is the Turtle Kraals cevicheria at the marina).

On Marc Certonio’s advice, we snagged a pair of tickets to the event at Charlie Mac’s, a local spot that has some of the best food in town. Juan Hernandez (right), the southeastern director for Domaine Select wines, was conducting a six-course, six-wine dinner for 30 people. I don’t even know where to begin, but suffice it to say that when the braised pork and pasta dish came out paired with a semi-dry Lambrusco, my eyes rolled back into my head. That was course four or five. At some point, Juan decided that seven courses was better than six; either that, or I just lost track. Chef Michael Schultz was the man behind the culinary madness. He is the chef for Pat Croce’s various restaurants and establishments in Key West and he has an unbelievable talent for all things fish. If you do one thing when you come down to Key West, eat at one of Chef Mike’s establishments (my favorite is the Turtle Kraals cevicheria at the marina).

AH, KYOTO

AH, KYOTO Though lighter in December, tourism at Kyoto’s top attractions is a year-round business. To beat the Chinese tourist buses, we rose early and visited the Kinkaku-ji Golden Temple (page 13), a very gold Buddhist temple. In concept, it dates back to 1398. But in fact it is a 1950s replica of the original, which was burned by a deranged monk. Another wonderful site is the Kiyomizu-dera Temple (left), founded in 778 and built in the 17th century with joinery (no nails) on a hillside overlooking Kyoto. While it is a Buddhist temple, Shinto shrines dot the grounds to “protect” the wooden temple from fire. Visitors often seek blessings and good fortune; they can drink from a spring-fed waterfall that is said to have wish-granting powers, leave petitions to the gods, or purchase good luck talismans. A former practice (fueled by the belief that anyone who survived a 13-foot jump from the temple veranda would have wishes fulfilled) wisely is prohibited now.

Though lighter in December, tourism at Kyoto’s top attractions is a year-round business. To beat the Chinese tourist buses, we rose early and visited the Kinkaku-ji Golden Temple (page 13), a very gold Buddhist temple. In concept, it dates back to 1398. But in fact it is a 1950s replica of the original, which was burned by a deranged monk. Another wonderful site is the Kiyomizu-dera Temple (left), founded in 778 and built in the 17th century with joinery (no nails) on a hillside overlooking Kyoto. While it is a Buddhist temple, Shinto shrines dot the grounds to “protect” the wooden temple from fire. Visitors often seek blessings and good fortune; they can drink from a spring-fed waterfall that is said to have wish-granting powers, leave petitions to the gods, or purchase good luck talismans. A former practice (fueled by the belief that anyone who survived a 13-foot jump from the temple veranda would have wishes fulfilled) wisely is prohibited now. ON TO TAIWAN

ON TO TAIWAN We arrived in Taipei on Christmas and, happy to forego our traditional heavy Christmas dinner, we dined at James Kitchen, an informal and quirky Taiwanese restaurant a local friend had recommended. Our taxi dropped us off on winding Yongkang Street, which is lined with hip shops and restaurants, and we entered a narrow building cramped with diners. The owner led us past the kitchen, up rickety steps to a tatami room, with customers’ drawings covering every inch of the walls and ceilings so low I couldn’t stand up. Seated on cushions at our low table, we enjoyed mushroom dumplings, pork lard rice, sautéed vegetables and the fish that James Kitchen is known for. Our check was about $15 per person

We arrived in Taipei on Christmas and, happy to forego our traditional heavy Christmas dinner, we dined at James Kitchen, an informal and quirky Taiwanese restaurant a local friend had recommended. Our taxi dropped us off on winding Yongkang Street, which is lined with hip shops and restaurants, and we entered a narrow building cramped with diners. The owner led us past the kitchen, up rickety steps to a tatami room, with customers’ drawings covering every inch of the walls and ceilings so low I couldn’t stand up. Seated on cushions at our low table, we enjoyed mushroom dumplings, pork lard rice, sautéed vegetables and the fish that James Kitchen is known for. Our check was about $15 per person To my mind, the most compelling reason to visit Taipei is to view the world’s finest collection of Chinese art at the National Palace Museum just north of the city. How did these treasures land in Taiwan? When Chiang Kai-shek made his speedy exit from China, he and his KMT (Kuomingtang) troops had time to cart away crates of nearly 700,000 exceptional works of art formerly owned by millennia of emperors. Here the peerless imperial treasures—jades, Neolithic bronzes, porcelains, painting and calligraphy scrolls, jeweled mystery boxes—are exhibited with clear explanations in Chinese, Japanese and English. With exhibits rotating several times in a year, it would take over 30 years to display the entire collection. On our visit, we saw rare jade carvings, fine Song Dynasty celadon porcelains and stunning bird, animal and flower paintings by Giuseppe Castiglione—an 18th century Jesuit priest who began his stay in China as an Italian missionary. Castiglione became a trusted Imperial court painter who also created portraits of the Empress and Emperor during the height of the Qing Dynasty

To my mind, the most compelling reason to visit Taipei is to view the world’s finest collection of Chinese art at the National Palace Museum just north of the city. How did these treasures land in Taiwan? When Chiang Kai-shek made his speedy exit from China, he and his KMT (Kuomingtang) troops had time to cart away crates of nearly 700,000 exceptional works of art formerly owned by millennia of emperors. Here the peerless imperial treasures—jades, Neolithic bronzes, porcelains, painting and calligraphy scrolls, jeweled mystery boxes—are exhibited with clear explanations in Chinese, Japanese and English. With exhibits rotating several times in a year, it would take over 30 years to display the entire collection. On our visit, we saw rare jade carvings, fine Song Dynasty celadon porcelains and stunning bird, animal and flower paintings by Giuseppe Castiglione—an 18th century Jesuit priest who began his stay in China as an Italian missionary. Castiglione became a trusted Imperial court painter who also created portraits of the Empress and Emperor during the height of the Qing Dynasty The ancient Chinese have a proverb: “Walking 10,000 miles is better than reading 10,000 books.” When visiting any foreign country, we learn a great deal experiencing firsthand its scenery, sites, food and people. During our five-day stay in Taiwan, I noticed something that I had been blind to when I lived there as a student many decades ago. I was struck by how polite, kind and helpful local strangers were to us and to each other. Whether at Christmas or anytime of the year (except hot, humid typhoon months of July and August) visiting Taiwan is a lovely experience

The ancient Chinese have a proverb: “Walking 10,000 miles is better than reading 10,000 books.” When visiting any foreign country, we learn a great deal experiencing firsthand its scenery, sites, food and people. During our five-day stay in Taiwan, I noticed something that I had been blind to when I lived there as a student many decades ago. I was struck by how polite, kind and helpful local strangers were to us and to each other. Whether at Christmas or anytime of the year (except hot, humid typhoon months of July and August) visiting Taiwan is a lovely experience GEISHAS, GEISHAS EVERYWHERE

GEISHAS, GEISHAS EVERYWHERE

Making my way from a coffee shop to the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum is as jarring as it gets for an American war veteran. Not too far away is a monument to John McCain’s seizure at Truch Bac Lake (left), commemorating where he parachuted after being shot down in 1967. Equally disconcerting was passing through the doors of Hoa Lo Prison (aka the Hanoi Hilton), where captured soldiers and airmen were subjected to deprivation and torture. American POWs had more prescient gallows humor than they knew. The twenty-five-story Hanoi Towers overshadows the infamous prison these days. The day I visited Hanoi’s university, the Temple of Literature, built in 1076, I watched proud parents taking pictures of recent grads with their diplomas. They were happy to pose with me, too.

Making my way from a coffee shop to the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum is as jarring as it gets for an American war veteran. Not too far away is a monument to John McCain’s seizure at Truch Bac Lake (left), commemorating where he parachuted after being shot down in 1967. Equally disconcerting was passing through the doors of Hoa Lo Prison (aka the Hanoi Hilton), where captured soldiers and airmen were subjected to deprivation and torture. American POWs had more prescient gallows humor than they knew. The twenty-five-story Hanoi Towers overshadows the infamous prison these days. The day I visited Hanoi’s university, the Temple of Literature, built in 1076, I watched proud parents taking pictures of recent grads with their diplomas. They were happy to pose with me, too. Hanoi was only one stop on my three-week odyssey. In South Vietnam, my friends and I idled a few days in the seaside resort of Vung Tau, called Cap Saint-Jacques by the French. Gorgeous mountain lookouts and theme parks feature huge statues: the Buddha atop one and Jesus another. Our B&B was opposite a wonderful seafood restaurant, where we dined among what looked like members of Vietnamese high society celebrating Christmas. In Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), Christmas carols blasted day and night from commercial malls and government offices everywhere in the Communist metropolis. Gift-wrapped packages were stacked in store windows, hotel clerks wore red Santa Claus hats, and Christmas trees were decorated with bright lights and outsized ornaments. The incongruity of it all suggested we may have lost the military conflict, but we won the cultural war. The Vietnamese may have to decide one day if that’s a good thing

Hanoi was only one stop on my three-week odyssey. In South Vietnam, my friends and I idled a few days in the seaside resort of Vung Tau, called Cap Saint-Jacques by the French. Gorgeous mountain lookouts and theme parks feature huge statues: the Buddha atop one and Jesus another. Our B&B was opposite a wonderful seafood restaurant, where we dined among what looked like members of Vietnamese high society celebrating Christmas. In Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), Christmas carols blasted day and night from commercial malls and government offices everywhere in the Communist metropolis. Gift-wrapped packages were stacked in store windows, hotel clerks wore red Santa Claus hats, and Christmas trees were decorated with bright lights and outsized ornaments. The incongruity of it all suggested we may have lost the military conflict, but we won the cultural war. The Vietnamese may have to decide one day if that’s a good thing In 1969, as a young Army lieutenant, I flew along the Cambodian border in a Birddog observation plane, spending my days looking for North Vietnamese troops. The bomb-cratered landscape I surveilled resembled the moon Neil Armstrong stepped onto that same year. Occasionally, what sounded like the intermittent buzzing of mosquitos around our plane drew my attention to muzzle flashes from shooters a thousand feet below. As quickly as they appeared, they skedaddled into their hidey-holes on the side of the border we weren’t supposed to cross. Being a target of small arms fire will instantly snap you out of revaries contemplating the natural scenic beauty of Vietnam. And out of the remorse for what a large country can do to destroy a small one.

In 1969, as a young Army lieutenant, I flew along the Cambodian border in a Birddog observation plane, spending my days looking for North Vietnamese troops. The bomb-cratered landscape I surveilled resembled the moon Neil Armstrong stepped onto that same year. Occasionally, what sounded like the intermittent buzzing of mosquitos around our plane drew my attention to muzzle flashes from shooters a thousand feet below. As quickly as they appeared, they skedaddled into their hidey-holes on the side of the border we weren’t supposed to cross. Being a target of small arms fire will instantly snap you out of revaries contemplating the natural scenic beauty of Vietnam. And out of the remorse for what a large country can do to destroy a small one. Nga motioned for me to sit. She kept leaving the small kitchen area to compose herself and catch her breath. She said something about me being like a detective to find her, still in shock until she finally settled beside me. I’d brought along some old pictures. Our great friend Hung, her best friend Lan (above left), and my fellow lieutenants: Fly, Sam, and Jim. We lingered over the images of parties at her house. Ba Muoi Ba beer bottles littered tables filled with spring rolls, pho, and other delicacies—my first introductions to what is now world-famous cuisine. What news of Lan? I was distressed to learn she was “sick now,” living with her family just a few houses down the street. Of course, I wanted to visit her.

Nga motioned for me to sit. She kept leaving the small kitchen area to compose herself and catch her breath. She said something about me being like a detective to find her, still in shock until she finally settled beside me. I’d brought along some old pictures. Our great friend Hung, her best friend Lan (above left), and my fellow lieutenants: Fly, Sam, and Jim. We lingered over the images of parties at her house. Ba Muoi Ba beer bottles littered tables filled with spring rolls, pho, and other delicacies—my first introductions to what is now world-famous cuisine. What news of Lan? I was distressed to learn she was “sick now,” living with her family just a few houses down the street. Of course, I wanted to visit her. Nga and I held time at bay for several hours, though not quite turning back the clock. Familiarity returned; romance less so. I realize now that a lonely soldier confused warm companionship and a dollop of guilt with true love. I won’t diminish what Nga and I had during the war. Had I brought her home to America, there’s an even chance we might have grown to love each other enough for a marriage to prosper and thrive. And just as likely she might have become homesick and discontented with a fast-paced and rapidly changing society so different from her traditional life in Vietnam. The exigencies of fate won’t allow a resolve to these hypotheticals.

Nga and I held time at bay for several hours, though not quite turning back the clock. Familiarity returned; romance less so. I realize now that a lonely soldier confused warm companionship and a dollop of guilt with true love. I won’t diminish what Nga and I had during the war. Had I brought her home to America, there’s an even chance we might have grown to love each other enough for a marriage to prosper and thrive. And just as likely she might have become homesick and discontented with a fast-paced and rapidly changing society so different from her traditional life in Vietnam. The exigencies of fate won’t allow a resolve to these hypotheticals.