Forget about math…food is the universal language.

As a child, I loved to eat. Food was everything to me. In fact, it’s been said that my first word was “bread.” It’s hard to find a picture of me as a toddler without a piece of bread in my hand or my mouth. My favorite toys were the pots and pans and wooden spoons in the kitchen. At age five, when most boys wanted a new Tonka truck, I asked for an Easy-Bake Oven. I received one and I used it to create my first masterpiece, a chocolate cake baked with the heat of a 100-watt lightbulb.

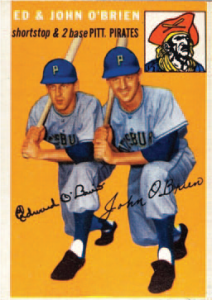

Courtesy of Justin Sutherland

From the beginning, the near-sacred importance of sitting down to a meal as a family was ingrained in me. My parents divorced when I was young. My mother, who was a flight attendant and often traveling, still always made sure we sat down at the dinner table and ate together. Even preparing for and cleaning up after the meal was a family affair: One brother set the table, one cleared the table, and one swept the floor, and everyone helped with the dishes (although not without the occasional pushback). Our meals were never fancy, and my mother’s signature dishes are still my three favorite meals of all time—but only when cooked by her: spaghetti with meat sauce, tater-tot hot-dish with chicken and broccoli, and her famous fried rice.

It wasn’t until I started eating at friends’ houses at sleepovers that I realized how special our mealtime really was. I come from a very diverse and multicultural family. On my mother’s side, my grandmother Masako came to this country from Japan during the Korean War speaking no English and at a time when the United States had poor relations, to say the least, with Japan. She wasn’t allowed to bring any of her culture to this country for fear of repercussions from the United States government. My grandfather on that side is a 6-foot, 5-inch Viking of Norwegian descent, a product of the Great Depression, from a family of farmers and carpenters.

On my father’s side, I am the descendant of slaves and sharecroppers. My grandfather, Harold, came up from Mississippi and settled in Waterloo, Iowa, with my Grandma Zona. Food was Zona’s love language and her food was the start of my love of soul food and barbecue.

It was the combined cultures of my family that gave me my first glimpse into the vast possibilities that foods brought to the world. The day I realized that not all family dinners consisted of Southern collard greens, Japanese sushi, and Norwegian lefse (a potato flatbread), all together on the same table, was the first time I realized we were different. I loved it and I wanted to learn and experience more.

With my Grandma Masako unable to truly share her culture, or even to teach her own children her language, her food was the gateway to her story. At a young age, I followed her around the kitchen, tasting everything from rice balls filled with pickled plums to somen—or, as we called them, “summer noodles”—pickled daikon and mochi, to tonkatsu and, my all-time favorite, sukiyaki, a one-pot family-style dish that filled my

brothers and me with so much joy every time she shared it. Whenever we could, we would invite our white American friends to her house to share our grandmother with them and let them experience this magic in a pot.

Burnell, my Norwegian grandfather, taught me the importance of respecting food. He taught me that no meal was ever complete without a slice of bread with butter and a glass of cold milk. As a product of a farming family during the Depression, he instilled in all of us the rule that we must never waste food, and, if food was prepared for you, you ate it all. Even when he became financially secure, he still would cut the mold off a block of cheese, because the rest of it was still good and not to be wasted. And you never left the table until your plate was clean.

Burnell gave me an appreciation for good, wholesome Midwest comfort food. He was all meat and potatoes. His wife, my Japanese grandmother, learned how to prepare pot roast, Swedish meatballs, spareribs with sauerkraut, and meatloaf. Burnell and I would make a weekly trip to the VFW post for the lutefisk dinner—the lye-soaked fish covered in a mystery white sauce alongside what had to be boxed white potatoes. But I always cleaned my plate, because that’s what you did when you ate with Grandpa. These foods were humble, but to this day, they always remind me of the importance of respecting food. Nothing must be wasted, and a meal is never complete without bread and butter.

Grandma Zona was the Big Mama to her neighborhood. She was a mother to so many neighborhood kids and, although she never had a lot of money, she always made sure that anyone and everyone who came to her table was fed. From church basement lunches (which were sorely needed after a five-hour Methodist service) to Saturday cookouts to every meal in between, she loved to cook, she loved to serve food, and she loved to protect.

It was something of a culture shock when we would travel from our suburban life in Apple Valley, Minnesota, to visit Grandma Zona in what, in my young mind, was “the hood.” There was clearly a disparity between what I had at home and what I experienced in her neighborhood. But I found a very tight-knit and connected community there. It gave me a chance to experience a different way of life—sitting on the front stoop shooting dice, foolishly playing chicken with oncoming trains, or riding bikes to the corner store to get my uncle a pack of cigarettes, knowing I would be able to keep the change to buy a couple Laffy Taffy candies or Lemonheads. With my brothers and cousins, I explored the many abandoned houses and we would take off running when we found a squatter. It was such a different life from where I lived, but I loved it.

All of the happiness and connection in this community was most visible in its food, and especially its soul food. In Grandma Zona’s kitchen, it seemed as if there was always a pot of collard greens on the stove, someone cleaning chitlins with a toothbrush, and a vat of hot oil just waiting for perfectly breaded chicken to be submerged.

Then there were the barbecues. Now, we aren’t talking about the weekend warriors with their Big Green Eggs or other trendy smokers or grills in the driveway. This was the whole neighborhood coming together at a local park to cook, commune, and throw down. It was the deacons from church alongside the neighborhood drug dealers, gang members of different affiliations, absent fathers, and baby mamas—and everyone was somehow your cousin. They all put everything aside to come together to grill and eat. My uncle Hawkeye always manned the grill with his 40-ounce beer in one hand and the barbecue didn’t stop until there were no more coals. This food spoke to me. It was something more than a meal. It had heart. It tasted like family. But what it really was all about, I believe, was that it had soul.

My life continued on this path, in which the love of food shared with my family was at the center of everything that mattered, for many years. As I matured, I became not just an observer of food but an active student of it. I ate everything I could, everywhere I could. I especially found myself wanting to learn more about the South, about soul food—the food that spoke to me most.

When I decided to turn food into a career, I moved to Atlanta. I had gone earlier to business school, but at the suggestion of my father, Kerry, and with a lot of encouragement from him and others, I decided to

pivot in a new direction and go to culinary school. I chose Atlanta because I wanted to be close to the foods of the South and the people who mastered them. I began to explore firsthand the dining and cooking of the South, from New Orleans to St. Louis, Mississippi to Georgia, Alabama to Texas. Spending time in these places filled my nose with the smells of soulful foods. It filled my stomach with their flavors. And it fed my soul.

When I moved back home to Minnesota and decided to open my first restaurant, Handsome Hog, the most important thing for me was to share those feelings and experiences. As my Grandma Zona had done for me, I wanted to welcome everyone to my table and help feed their souls. And I want to pay homage to the memories and the feelings of that soul food…the food that was smuggled into the United States by my ancestors—beans and seeds hidden in the hair of West African women in the slave trade who were stolen from their homes as labor to build this country.

This food encompasses the unwanted scraps that were discarded and left to our people, and that have now become soughtafter delicacies. This is food that was enjoyed in generations of Southern restaurants, with white owners in the front while the true culinary geniuses worked out of sight in the back. In the book Northern Soul, I tell these stories through the lens of all of my experiences, not just my origin and my family, but also through my training in classic French cuisine and fine dining, and my many years of national and international travel—for which I thank my flight-attendant mother. As a born Northerner, this is the food that resonates with me, that feeds my soul. The recipes in Northern Soul are the stories of my life. Here are three that celebrate the bounty of summer—not just in New Jersey, but wherever you happen to call “home.”

www.istockphoto.com

Watermelon Salad

with Bourbon Vinaigrette

SERVES 6 TO 10

Nothing signals the arrival of summer like watermelon! This salad is a fresh way to enjoy this amazing fruit and will definitely make you the star of the BBQ. Just remember: If you swallow a seed, a watermelon might grow in your stomach!

1 medium watermelon, seeded and cut into 1-inch (2.5 cm) cubes

2 English cucumbers, seeded and cut into 1⁄2-inch (1 cm) slices

2 cups (40 g) baby arugula

1⁄4 cup (35 g) sliced pickled chiles

1 large shallot, cut horizontally into thin rings

1⁄4 cup (25 g) toasted pecans

1 tablespoon (18 g) smoked salt

- Toss together the watermelon, cucumbers, arugula, chiles, shallot and pecans in a salad bowl.

- Toss the salad ingredients with the vinaigrette (below), sprinkle smoked salt over the top and serve.

Bourbon Vinaigrette

MAKES ABOUT 3 CUPS (705 ML)

A delicate part of this recipe is igniting the bourbon to cook off the alcohol and enhance the deep, smoky flavors that make it so distinctive. Cook the reduction in a well-ventilated space and over a low flame to prevent any loose clothing, or, in my case, substantial facial hair, from catching fire. That will ruin any party.

1 cup (235 ml) bourbon

1⁄2 cup (176 g) Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons (22 g) whole-grain mustard

1⁄2 cup (118 ml) apple cider vinegar

1⁄4 cup (40 g) minced shallots

2 tablespoons (26 g) sugar

1 tablespoon plus 3⁄4 teaspoon (7 g) freshly ground black pepper

1 1⁄2 teaspoons kosher salt

1 cup (235 ml) extra virgin olive oil

- Heat the bourbon in a saucepan over medium heat until the fumes ignite. Continue to cook over low heat, swirling constantly, until the flame dies out. Remove from the heat and allow to cool to room temperature.

- Whisk together the bourbon, both mustards, vinegar, shallots, sugar, pepper, and salt in a large mixing bowl. Slowly drizzle the olive oil into the bowl while whisking vigorously to emulsify.

- Serve immediately or store in an airtight container in your refrigerator. Allow to come to room temperature before using.

Asha Belk

Shrimp Po’Boy

In my dreams, I walk into a perfectly manicured backyard garden surrounded by my friends. The magnolias are in full bloom. Someone places a tall bourbon cocktail in my hand. I can smell the smoke and caramelizing meat of a well-tended barbecue pit and there—on the buffet table—next to a mountain of shucked oysters on ice, acres of deviled eggs, and a bowl of hush puppies, is a pile of shrimp po’ boys stacked like cordwood. There’s one for everybody, and they’re still warm. I’m passing along this recipe because I want you to help make my dream come true.

MAKES 2 SANDWICHES

Peanut oil for deep-frying

12 large (size 16/20) shrimp, peeled and deveined

1 cup (140 g) finely ground cornmeal

1⁄2 cup (63 g) all-purpose flour

1⁄2 cup (50 g) Cajun Seasoning (page 13)

1⁄2 cup (118 ml) buttermilk

2 hoagie rolls

1⁄4 cup (63 g) Remoulade

1⁄2 cup (28 g) shredded iceberg lettuce

2 plum tomatoes, cut 1⁄4-inch (6 mm) thick

- To make the shrimp, heat the peanut oil in a deep-fryer or Dutch oven to 350°F (177°C). Set out a wire rack for draining the fried shrimp.

- Make a dredge for the shrimp by combining the cornmeal, all-purpose flour, and Cajun Seasoning in a bowl. Submerge the shrimp in the buttermilk. Remove them, let them dry briefly, then toss them to coat in the dredge.

- Working in batches, fry the shrimp for 2 to 3 minutes until golden brown and cooked through. Drain briefly on the wire rack.

- To assemble the sandwiches, slather the insides of the hoagie rolls generously with the remoulade. Add the iceberg lettuce and sliced tomato, and finish with the breaded shrimp, fresh out of the deep-fryer. Serve immediately.

Asha Belk

Go-To Cajun Seasoning

All of the ingredients in this recipe should be stocked in your pantry for use individually from time to time, so picking up any you may be missing is doing yourself as great a favor. Keep this blend at the ready for all sorts of meat, vegetables and seafood that make their way into your kitchen.

MAKES ABOUT 2 CUPS

1⁄2 cup plus 2 tablespoons (53 g) ground cayenne

1⁄4 cup (75 g) kosher salt

1⁄4 cup (36 g) garlic powder

1⁄4 cup (28 g) sweet paprika

2 tablespoons (14 g) onion powder

2 tablespoons (5 g) dried thyme

2 tablespoons (6 g) dried oregano

2 tablespoons (12 g) freshly ground black pepper

- Mix together the cayenne, salt, garlic powder, paprika, onion powder, thyme, oregano and pepper in a bowl.

- Use immediately or transfer to an airtight container and store in a cool, dark place for up to 4 weeks.

Asha Belk

Lobster Étoufée

Étouffée means stuffed or smothered. This dish is smothered in deliciousness, not to mention topped with a whole lobster tail. This ain’t your grandma’s étouffée.

SERVES 4

6 tablespoons (85 g) unsalted butter

2 cups (320 g) diced white onion

1 cup (150 g) diced green pepper

1 cup (120 g) diced celery

4 garlic cloves, minced

1⁄4 cup (31 g) all-purpose flour

2 cups (390 g) uncooked white rice

2 quarts (1.9 L) shellfish stock, seafood stock, or fish stock

1 (15.5 ounce / 439 g) can whole tomatoes, drained and coarsely chopped

3 tablespoons (36 g) Cajun Seasoning (page 13)

1 tablespoon (15 g) habanero hot sauce

1 tablespoon (2 g) fresh thyme leaves

2 bay leaves

2 tablespoons (28 ml) Worcestershire sauce

1⁄4 cup (59 ml) fresh lemon juice

8 ounces (225 g) lobster claw meat

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

4 small to medium lobster tails

4 lemon wedges

- In a large skillet or Dutch oven, melt 4 tablespoons (55 g) of the butter over medium heat. Add the onion, green pepper, celery, and garlic and cook for 2 minutes, stirring often. Whisk in the flour until a roux just begins to form, 2 to 3 minutes more.

- Cook the rice according to the package instructions and keep warm, if necessary, until it is needed.

- Add the stock to the vegetable-roux mixture and stir thoroughly, taking care that there are no lumps in the roux. Add the tomatoes, 2 tablespoons (24 g) of the Cajun seasoning, hot sauce, thyme, bay leaves, Worcestershire sauce, and lemon juice. Bring to a low simmer and cook for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally.

- Add the lobster meat and cook for 5 minutes more. Add some additional stock if the sauce is too thick. Add salt and pepper to taste and keep the mixture warm over low heat.

- With kitchen scissors, cut a slit in the top of each lobster tail from the front to the end of the tail. Using a fork or spoon, pull the tail meat out through the slit and let it rest on top of the shell.

- Preheat the broiler to 500°F (250°C). Meanwhile, transfer the tails to a broiler-ready sheet pan. In a separate pan, melt the remaining 2 tablespoons (28 g) of butter. Brush this butter onto the lobster tail meat and sprinkle the remaining 1 tablespoon (12 g) of Cajun seasoning on top. Broil the tails for 6 to 8 minutes, until the meat is cooked through.

- Divide the rice among 4 plates. Pour the sauce over the rice and top each serving with a lobster tail. Serve with lemon wedges.

A dear friend of mine often says, “Everything good in my life started over a meal.” No words ever rang truer. Food is so much more than a means to an end. More than just the calories and nutrients that sustain our physical lives, food is a fuel that powers us spiritually and emotionally, too. Food tells a story, evokes memories, bridges gaps and connects humanity by a singular thread.

Courtesy of Justin Sutherland

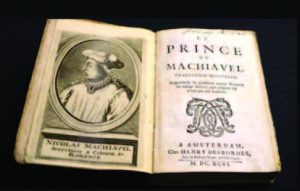

Editor’s Note: Justin Sutherland is familiar to EDGE foodies for his appearance on Top Chef and his victory on Iron Chef America, as well as a hosting gig on Fast Foodies. He completed Northern Soul in 2022 while recovering from a near-fatal boating accident. He narrowly escaped the loss of an arm and an eye, but is back in the kitchen and on his way to a full recovery. Justin was recently featured in a segment by friend of EDGE Tamron Hall on her talk show…and his book has since taken off. It is available from The Harvard Common Press, an imprint of The Quatro Group.

Asha Belk’s food photography has been featured in several books and magazines. In 2021, her work documented the civil unrest following the death of George Floyd.

University of Virginia and thought I might go into politics, because I was a page in the General Assembly and my mom ran campaigns. Later, she was the Director of Consumer Affairs for the Commonwealth of Virginia. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer and sort of segue into politics. I won this contest on Oprah Winfrey and it changed the trajectory of my life. My father had died when I was quite young and my mom raised me and my three older sisters. We weren’t a family that traveled. Before my mother and I moved to Richmond, we lived in Lovingston, which was such a country town—like if you needed new sneakers, you had to drive 35 miles to Charlottesville. Our big thing was we went to Virginia Beach. One time we went to Disney World. Suddenly, I was traveling to Europe. It was definitely wild. [Laughs] I’m grateful and feel like something in this lifetime I did right. It feels good.

University of Virginia and thought I might go into politics, because I was a page in the General Assembly and my mom ran campaigns. Later, she was the Director of Consumer Affairs for the Commonwealth of Virginia. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer and sort of segue into politics. I won this contest on Oprah Winfrey and it changed the trajectory of my life. My father had died when I was quite young and my mom raised me and my three older sisters. We weren’t a family that traveled. Before my mother and I moved to Richmond, we lived in Lovingston, which was such a country town—like if you needed new sneakers, you had to drive 35 miles to Charlottesville. Our big thing was we went to Virginia Beach. One time we went to Disney World. Suddenly, I was traveling to Europe. It was definitely wild. [Laughs] I’m grateful and feel like something in this lifetime I did right. It feels good.

DOTS Candy

DOTS Candy

Editor’s Note:

Editor’s Note:

account is empty. According to the critics of Artificial Intelligence—including the geniuses who created it—this is one version of the dark future that supposedly awaits us if we don’t get a handle on AI.

account is empty. According to the critics of Artificial Intelligence—including the geniuses who created it—this is one version of the dark future that supposedly awaits us if we don’t get a handle on AI.

assistant could not only read bedtime stories, but could customize those stories for each child, embracing favorite themes or reinforcing lessons learned that day. The same device would also be smart enough to shield a child from inappropriate content, and weigh in on concepts such as good and bad and right and wrong. Parents would be able to control an AI assistant and set all kinds of parameters to ensure that their offspring grow up with the educational and cultural guardrails they choose. For tweens and teens, a trusted AI assistant could be helpful working through issues of social anxiety and depression.

assistant could not only read bedtime stories, but could customize those stories for each child, embracing favorite themes or reinforcing lessons learned that day. The same device would also be smart enough to shield a child from inappropriate content, and weigh in on concepts such as good and bad and right and wrong. Parents would be able to control an AI assistant and set all kinds of parameters to ensure that their offspring grow up with the educational and cultural guardrails they choose. For tweens and teens, a trusted AI assistant could be helpful working through issues of social anxiety and depression.

In May 2023, the Brookings Institution released findings on ARRIVE Together, looking at data from more than 300 calls between December 2021 and January of this year—including critically important Officer Narrative Reports. Dr. Rashawn Ray, a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies, joined New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin on a panel that included Lisa Dressner of RWJBarnabas Health, who is Vice President of the Department of Behavioral Health at Trinitas.

In May 2023, the Brookings Institution released findings on ARRIVE Together, looking at data from more than 300 calls between December 2021 and January of this year—including critically important Officer Narrative Reports. Dr. Rashawn Ray, a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies, joined New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin on a panel that included Lisa Dressner of RWJBarnabas Health, who is Vice President of the Department of Behavioral Health at Trinitas.

Krust Kitchen • Philly Special

Krust Kitchen • Philly Special Common Lot • Wagyu Beef Tartar

Common Lot • Wagyu Beef Tartar Trattoria Gian Marco • Calamari Toscano

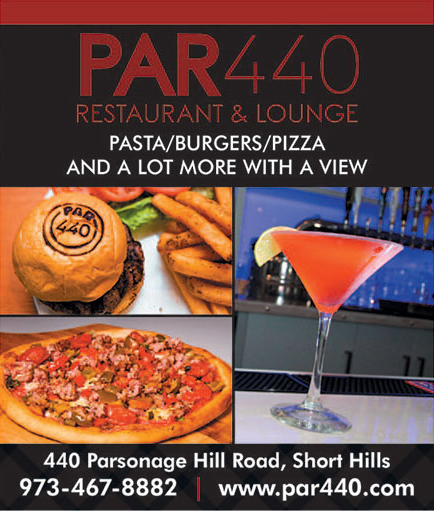

Trattoria Gian Marco • Calamari Toscano PAR440 • Mahi Mahi

PAR440 • Mahi Mahi Galloping Hill Caterers

Galloping Hill Caterers  Limani Seafood Grill • Pan Seared Chilean Sea Bass Barigoule

Limani Seafood Grill • Pan Seared Chilean Sea Bass Barigoule