According to leading New Jersey educators, the case for a challenging literature curriculum is open-and-shut.

A couple of months ago, I convened five of my old school girlfriends during our annual reunion to discuss our all-time favorite middle-school (we called it “junior high” back then) Summer Reading List titles. There was an immediate consensus about Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. These novels represented our first foray into more serious, more adult fiction, offering themes of rebellious angst, social injustice, and seemingly insurmountable challenges. We also agreed that, as parents (and now grandparents), we were all too familiar with the moaning and groaning of subsequent generations when presented with the dreaded list. Perhaps it’s overscheduling or shorter vacations or digital distractions, but it seems as if the “I can’t wait to read it” treasures of our early teens have become the “Do I have to read it?” chores for a lot of kids today.

www.thinkstockphotos.com

For generations the great literary safety net has been supplied by our schools. Whether reading comes naturally to a student or is a bit of a forced march, every child is exposed to the enlightening qualities of a great book sometime in the vicinity of 6th Grade, and in most systems the rubber meets the road in 7th. By high school, kids have been introduced to literature in a meaningful way; they get why reading matters. For some it sticks, for others it doesn’t.

The responsibility of educators is to inspire their students to read. (It’s up to authors to keep readers reading.) Some school systems in New Jersey do a magnificent job. Others have become less demanding of their students, and even of their teachers. In assessing the relative merits of a child’s educational options, parents would be wise to ask questions about how great literature fits into a school’s overall philosophy. We put this question to a number of top schools in the Garden State.

“The job of a teacher is not just to find the right book, but to start a student on a lifetime of reading pleasure.”

—Dr. Peter Lewis • Head of School The Winston School • Short Hills

Dr. Lewis defines the basic literacy goal for all students as “getting pleasure out of print,” adding that “with literature, we need to find a theme that will spark interest—but first we need to provide the techniques and strategy to decode the words, starting in the lower grades.” At Winston, non-fiction is typically factored in during the Middle School grades. Often the hero is a very ordinary human being who rises to meet and overcome challenges. For example, Mountains Beyond Mountains, by Tracy Kidder, is a book about Dr. Paul Farmer and his inspiring quest to cure infectious diseases around the world.

Be it fiction or non-fiction, Dr. Lewis believes that, from an academic perspective, all literature is still fundamentally “text,” and the challenge is to keep students enraptured by the written word rather than put off by the hurdles of decoding them. That effort includes booking author visits to add a living component to the books students are reading. On a school trip to see Orlando Bloom in Romeo and Juliet on Broadway, Bloom met with Winston students and explained that although he had been dyslexic as a child, he had managed to overcome his early challenges to pursue and achieve his lifelong dream of becoming a modern-day Shakespearean actor. Dr. Lewis used the opportunity to emphasize to his students that “Just because it’s hard to do, doesn’t mean you can’t do it.”

“Avid readers make awesome writers.”

—Mary Schoendorf • Middle School Literature Coordinator St. Bartholomew Academy • Scotch Plains

The kids at St. Bartholomew are in a “trilogy mode,” particularly by authors Suzanne Collins (The Hunger Games) and Veronica Roth (Divergent). Schoendorf has noticed that this popular reading genre has been influencing her students’ writing, which is immensely gratifying. Middle schoolers she notes, tend to be a bit unfocused in their writing. Often her role is to help fine-tune their efforts and come more quickly to the point they want to make.

To inspire her students’ interest in literature, Schoendorf regularly offers video clips about the authors to help bring them to life. She also insists on “web quests,” where students are required to research the author’s life and time—all before they even open the book. “This way,” she points out, “the book itself becomes the reward…and one that they can’t wait to start reading.”

Schoendorf also tries to nudge them out of their literary comfort zone into other genres (e.g., the classics). In doing so, she assesses class profiles in order to determine the most appropriate literature for the grade level, beginning with what she believes a class can emotionally handle. For example, she would ordinarily avoid Edgar Allan Poe, at least until the 7th Grade. For her 6th Graders, she might substitute The Hatchet, a young-adult wilderness survival novel by Gary Paulsen—an adventure story that is not as dark as Poe’s work, but offers all the same basic literary suspense elements. Recently, Schoendorf successfully introduced the 7th Graders to The Wednesday Wars, by Gary Schmidt—a coming-of-age story about a 7th grader. Her students were so impressed by the protagonist’s interest in Shakespeare that they asked for a Shakespeare unit in their own classroom, which is now known as Shakespeare Wednesdays. In fact, they even volunteered to give up half their recess for more class time with the Bard…which only proves her favorite point: “Get them interested, and they’ll bite.”

“Many of the most popular books fall into the category of dystopian literature, where the person who saves the world is a young adult.”

—Barbara Dellanno • Dean of Academic and Faith Formation Union Catholic High School • Scotch Plains

Dellanno, who doubles as Union Catholic’s Humanities Curriculum Specialist, sees the goal of both parents and teachers when it comes to young adult literature as “getting them hooked on reading for pleasure.” Her opinion about much of the YAL being written today is that it does just that. In fact, she admits to getting hooked herself on such contemporary classics as the Harry Potter series. Dellanno also believes it’s a positive for young readers to form their own tastes and reading habits. “I think that it is important that teachers and parents allow them to choose what they want to read,” she says, adding that there’s no harm in an occasional comic book or sports magazine.

The point is to get them reading and, once they develop the habit, they are more easily encouraged to branch out into serious literature, even the classics. Not surprisingly, Dellanno gives a thumbs-up to trending series literature, such as The Hunger Games, Twilight, Maze Runner, Divergent, Gone, and Park Service. As for singular novels, she favors The Book Thief and Wonder, as well as novels like Fahrenheit 451 and Persepolis. As for popular authors, continued on page 68 she lists Jerry Spinelli, Walter Dean Myers (a recently deceased resident of Jersey City), Sarah Dressen (for girls), and Elizabeth Wein (for historical fiction). “Dystopian-themed novels,” Dellanno notes, “are empowering and reflect a way for the younger generation to cope in a healthy way with our post-9/11 world.”

When asked why To Kill a Mockingbird seems to top everyone’s list of Middle School classics, Dellanno explains that it is a great tool to teach the important elements of fiction (setting, point of view, foreshadowing and symbolism), and that the 1962 film starring Gregory Peck enables students to compare and contrast great writing and great filmmaking techniques. “Also, the essential questions raised by the novel grip students and make them think and want to discuss what they have read with one another,” she says. The 1960 novel by Harper Lee happens to be Dellanno’s all-time favorite.

“The classics speak to the human condition and teach lessons about life to which all people can relate.”

—Dr. Martine Gubernat • Chair of English Department St. Joseph High School • Metuchen

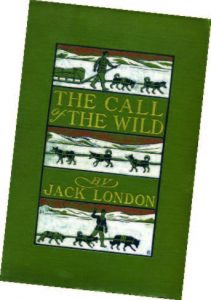

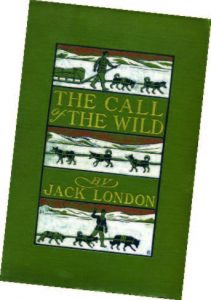

The freshmen boys at St. Joe’s dive right into great literature in English I, including short stories, nonfiction, drama, novels, mythology and poetry. During a typical year, they’ll digest Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Inherit the Wind and The Call of the Wild. This sets the stage for English II, which focuses on American literature; English III, which transports young readers across the ocean for a year of British lit.; and finally to English IV and AP classes that feature challenging selections of world literature.

According to Dr. Gubernat, classic literature is at the heart of the English curriculum all four years. “The classics,” she says, “help readers to consider the impact of events—both large and small, positive and negative—on ordinary people.” The “noble language” of the classics, she adds, serves as the basis for student analysis and evaluation of the written word.

“The written language is still king.”

—Whitney Slade • Head of School

The Rumson Country Day School • Rumson

www.thinkstockphotos.com

The 2014–15 school year will be Slade’s first at RCDS, an independent K–8 school in Monmouth County with a strong historical commitment to fostering an appreciation of literature. The nature of how great writing is delivered, he notes, is changing…and with change comes trepidation on the part of parents and educators. “With the advent of the Internet and social media there is fear—real or imagined—that students will be distracted from reading and the joys of literature,” he says.

Slade believes that it is incumbent upon teachers, parents and caregivers to foster reading whenever possible. However, it needs to be on the young person’s terms. Whether reading an online version of a novel or a well-written publication, engaging in a worthy blog, or simply making a monthly visit to the bookstore, exposure is key. The form it comes in, he insists, should be irrelevant. “Good writing is as important as ever in binding us together, sharing a common history, fostering creativity, and developing skills for an unpredictable workplace,” Slade says.

“Books can evolve with you and your understanding of them can evolve, too…that’s just one wonderful thing about my job.”

—Lou Scerra • English Department Chair Newark Academy • Livingston

At first glance, the literary spread between 6th and 12th Grades at Newark Academy seems extremely ambitious. The 6th Graders are reading A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Nothing But the Truth, a novel about a boy suspended for humming the national anthem. The seniors are tackling

www.thinkstockphotos.com

Alison Bechdel’s 2006 graphic memoir, Fun Home, Junot Diaz’s Pulitzer-winning 2008 novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Virginia Woolf’s 1925 Mrs. Dalloway, and the playwright Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia. In between, students are introduced to Harper Lee, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Walt Whitman, Toni Morrison and John Green.

Serra, who heads the school’s literature-based English Department, points out that much of the literature he assigns is driven by story and character. He meticulously selects texts that are developmentally appropriate in terms of form and content, saying, “I’d like to think we have a nice blend of traditional classics and contemporary literature that all speak to the concerns of the 21st century world. We’re always eager to add new texts into the curriculum and we also try to listen to student input.”

Serra’s personal favorite is The Great Gatsby—the subject, as it happens, of his undergraduate thesis. Interestingly, he credits his sophomores with having helped him to “see the characters, the story, and the novel itself in a new way.”

Inside the Numbers

The U.S. publishing world generated $27.01 billion in net revenue in 2013, selling 2.59 billion units according to a recent report from the Association of American Publishers and BISG (Book Industry Study Group). A large chunk of that business is attributable to YAL. In December of last year, a report on CBS News indicated YAL sales were up 24 percent since 2010, making it the fastest-growing publishing market sector. Long overlooked by the big publishers, these books have actually become popular with adults, too; the report estimated that about 80 percent of YAL buyers are over 18…and not all of them are buying for kids.

www.thinkstockphotos.com

In terms of embracing non-paper delivery methods, the news is also positive. An article in New York Magazine last year entitled “YAL by the Numbers” showed that, in 2002, fewer than 5,000 YA titles were published—of which only 143 were ebooks. By 2012, the number of titles had more than doubled over 10,000, of which 40 percent were of the ebook variety.

Good literature comes in many shapes and sizes—from traditionally leather-bound library tomes to dog-eared and page-worn paperbacks to the latest palm-held backlit digital readers. There are some among us who would never trade that special feeling that comes from physically opening a “real” book and thumbing through it page-by-page. On the other hand, the popularity of audio and ebooks, whether delivered to a Kindle, a Nook, or some other experience-enhancing device, has expanded exponentially, especially among the younger generation. Whatever or however a person prefers to read, it is the actual commitment to read that really matters. And for that we count on our educators—more heavily now than ever.

SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A YOUNG ADULT BEST-SELLER…

SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A YOUNG ADULT BEST-SELLER…

In a recent article in Atlantic Magazine by Nolan Feeney, “The 8 Habits of Highly Successful Young-Adult Fiction Authors,” several recognized authors shared their secrets to success. To be a winner, a YA book of fiction must be:

- Attention-grabbing…from the minute the book is opened until the last page is read.

- Age-appropriate…with someone in the book being a peer of the targeted reader.

- Relatable…to teenage experiences, even some that may be dark, but familiar.

- Meaningful…inspirational but in a realistic way.

- Believable…from an author who can think like a young teen and sound like one, too.

- Respectful…with no patronizing or “dumbing down” of information.

DIRTY DOZEN

DIRTY DOZEN

John F. Kennedy once said that libraries should be open to everyone—“except the censors.” At one time or another, some of the great works of American Literature were included on official lists of Banned Books for public schools and libraries, including the 12 below. All, by the way, made it onto another list: the Library of Congress Books That Shaped America…

The Scarlet Letter • Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850)

Moby Dick • Herman Melville (1851)

Leaves of Grass • Walt Whitman (1855)

The Red Badge of Courage • Stephen Crane (1895)

The Call of the Wild • Jack London (1903)

The Great Gatsby • F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

Gone with the Wind • Margaret Mitchell (1936)

The Grapes of Wrath • John Steinbeck (1939)

For Whom the Bell Tolls • Ernest Hemingway (1940)

The Catcher in the Rye • J. D. Salinger (1951)

To Kill a Mockingbird • Harper Lee (1960)

Where the Wild Things Are • Maurice Sendak (1963)

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS

Benedictine Academy, an all-female, private, Catholic college-preparatory school for grades 9-12 in Elizabeth, celebrates its Centennial this September through April 2015. A Mass and reception on September 21 kick off a year-long calendar of celebrations, including renowned speakers and a grand finale gala. Check the Academy website (benedictineacad.org) for more information or call 908-352-0670 x 105/106. A four-time Jefferson Award-winning, 21st Century learning environment, the Academy emphasizes rigorous academics, including honors and AP courses, and offers five varsity sports—plus service outreach, clubs and extracurricular activities for every interest. Technology includes personal laptops (provided), campus-wide wi-fi, interactive SMARTBoards, and a state-of-the-art science lab. Scholarships and tuition assistance are available.

“All of my life, I have watched my family do charitable work,” she explains. “My grandfather was a physician, my mother was a physician, and through them doing their jobs, I felt like this was a career I wanted to pursue—where I could actually go out into the community to help people and gain personal satisfaction from contributing to medical society.”

“All of my life, I have watched my family do charitable work,” she explains. “My grandfather was a physician, my mother was a physician, and through them doing their jobs, I felt like this was a career I wanted to pursue—where I could actually go out into the community to help people and gain personal satisfaction from contributing to medical society.”

If you miss impatiens—not on the market due to Downy Mildew—a great substitute with a similar color palette is caladium. While not a flowering plant, caladium has heart-shaped leaves in a variety of colors—white, red and pink. Caladium can tolerate the growing challenges of summer months. You can plant it in a dry site in the shade and forget about it.

If you miss impatiens—not on the market due to Downy Mildew—a great substitute with a similar color palette is caladium. While not a flowering plant, caladium has heart-shaped leaves in a variety of colors—white, red and pink. Caladium can tolerate the growing challenges of summer months. You can plant it in a dry site in the shade and forget about it.

Kevin Bullard

Kevin Bullard

restrooms that don’t give the senses a break. That’s all deliberate, the brainchild of Seward Johnson, who, the year it opened, gave me a personal tour of Rat’s and the atelier he installed in the compound when I was on assignment for Town & Country magazine. Johnson was forward-thinking, connecting Rat’s (named after a loyal and hospitable character in the book The Wind in the Willows) to a farm at its birth, urging diners to tour the sculpture grounds before or after their meal, determined to make dinner an all-inclusive creative experience. The mission and the restaurant, reinforced today by the wide-ranging talents of chef Shane Cash in the kitch and the management of Philadelphia-based restaurateur Stephan Starr, never fail to warm my heart.

restrooms that don’t give the senses a break. That’s all deliberate, the brainchild of Seward Johnson, who, the year it opened, gave me a personal tour of Rat’s and the atelier he installed in the compound when I was on assignment for Town & Country magazine. Johnson was forward-thinking, connecting Rat’s (named after a loyal and hospitable character in the book The Wind in the Willows) to a farm at its birth, urging diners to tour the sculpture grounds before or after their meal, determined to make dinner an all-inclusive creative experience. The mission and the restaurant, reinforced today by the wide-ranging talents of chef Shane Cash in the kitch and the management of Philadelphia-based restaurateur Stephan Starr, never fail to warm my heart. Makeda, the Ethiopian restaurant in New Brunswick, was back in its early days, when it was located in a smaller space and the dining was joyfully cheek-to-jowl. It’s long settled in its larger digs in the college town and its imprint on the community is profound: A dear pal who teaches at Rutgers tells me that it’s not only where she takes all out-of-town guests and celebrates birthdays and anniversaries, but the cuisine has influenced her home-cooking. “Makeda transports me every time I eat here,” this professor says. “It’s a vacation in a couple of hours.” I agree, and that’s why this downtown destination owned by Peter Meme and Stuart Smith, with peerless chef Aster Kassa, is always on my go-to list. Sometimes romance is less about where you are, physically, and more about where a restaurant’s food and attitude can take you, spiritually. When at Makeda, I get away in the best possible way.

Makeda, the Ethiopian restaurant in New Brunswick, was back in its early days, when it was located in a smaller space and the dining was joyfully cheek-to-jowl. It’s long settled in its larger digs in the college town and its imprint on the community is profound: A dear pal who teaches at Rutgers tells me that it’s not only where she takes all out-of-town guests and celebrates birthdays and anniversaries, but the cuisine has influenced her home-cooking. “Makeda transports me every time I eat here,” this professor says. “It’s a vacation in a couple of hours.” I agree, and that’s why this downtown destination owned by Peter Meme and Stuart Smith, with peerless chef Aster Kassa, is always on my go-to list. Sometimes romance is less about where you are, physically, and more about where a restaurant’s food and attitude can take you, spiritually. When at Makeda, I get away in the best possible way.

TAKING IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL

TAKING IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL

For most of us, childhood memories of the Jersey Shore involve a cardboard box of old postcards, the odd seashell, and assorted snapshots of family vacations. For Emily Satloff, those memories are expressed in the artistry and design that has made her jewelry brand, Larkspur and Hawk, one of the hottest on the market. Satloff, a lifelong summer-and-weekend resident of a gracious Victorian home in Monmouth County, creates pieces that evoke memories of a warm, elegant way of life—of multi-generational gatherings of friends and families that moved easily between New York and New Jersey…and of countless hours spent browsing shore antique stores with her mother.

For most of us, childhood memories of the Jersey Shore involve a cardboard box of old postcards, the odd seashell, and assorted snapshots of family vacations. For Emily Satloff, those memories are expressed in the artistry and design that has made her jewelry brand, Larkspur and Hawk, one of the hottest on the market. Satloff, a lifelong summer-and-weekend resident of a gracious Victorian home in Monmouth County, creates pieces that evoke memories of a warm, elegant way of life—of multi-generational gatherings of friends and families that moved easily between New York and New Jersey…and of countless hours spent browsing shore antique stores with her mother. I first noticed Larkspur and Hawk during a party at a friend’s home. My eye was drawn to her stunning rose quartz and gold earrings. Having just been to Bergdorf’s, I thought I recognized the expensive designer who made them. Later, when I called my host to thank her—and complimented her on her jewelry—she informed me that I had actually met the designer that night at her house.

I first noticed Larkspur and Hawk during a party at a friend’s home. My eye was drawn to her stunning rose quartz and gold earrings. Having just been to Bergdorf’s, I thought I recognized the expensive designer who made them. Later, when I called my host to thank her—and complimented her on her jewelry—she informed me that I had actually met the designer that night at her house. In the last year, her business has taken off. But Satloff is determined to “grow smart” as she puts it, and not mass-produce. In the meantime, her jewelry is showing up on fashion plates (Tory Burch), the red carpet (Mariska Hartigay) and the silver screen (Friends with Kids). Something good and beautiful, inspired by New Jersey, is finally getting the right sort of attention.

In the last year, her business has taken off. But Satloff is determined to “grow smart” as she puts it, and not mass-produce. In the meantime, her jewelry is showing up on fashion plates (Tory Burch), the red carpet (Mariska Hartigay) and the silver screen (Friends with Kids). Something good and beautiful, inspired by New Jersey, is finally getting the right sort of attention.

WIN, PLACE OR SHOW

WIN, PLACE OR SHOW

importantly provides a consistent means of sharing recorded documentation among health care professionals who are involved in patient care and treatment.

importantly provides a consistent means of sharing recorded documentation among health care professionals who are involved in patient care and treatment.

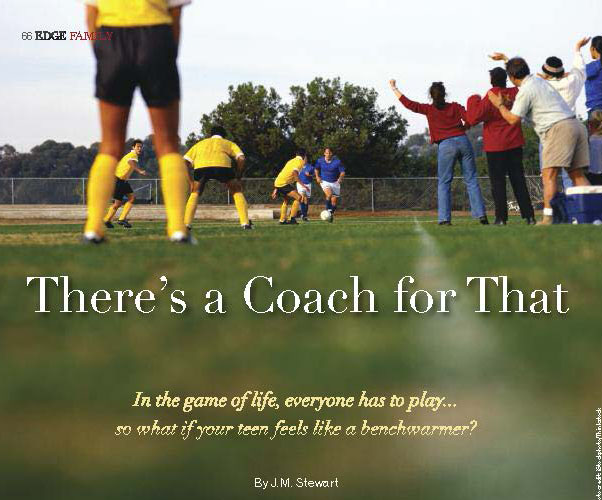

Rick Singer began his career as a coach and director of college-level athletics. For more than 25 years he has made a living as a life coach. He’s done life coaching in the corporate environment, as well on the student level. He has helped countless high-school student-athletes follow their dreams and play college sports, and worked with sports celebrities in planning their goals once their playing careers were over. Singer has been most successful working with teens and young adults in finding a college that is an appropriate fit. He cannot emphasize enough the importance of that “fit”—which is why he named his company The Key.

Rick Singer began his career as a coach and director of college-level athletics. For more than 25 years he has made a living as a life coach. He’s done life coaching in the corporate environment, as well on the student level. He has helped countless high-school student-athletes follow their dreams and play college sports, and worked with sports celebrities in planning their goals once their playing careers were over. Singer has been most successful working with teens and young adults in finding a college that is an appropriate fit. He cannot emphasize enough the importance of that “fit”—which is why he named his company The Key.

California Cool

California Cool Drop-Dead Good, Y’all

Drop-Dead Good, Y’all Link Between Folic Acid and Autism

Link Between Folic Acid and Autism The Slim Jim Diet

The Slim Jim Diet Oils Well that Ends Well?

Oils Well that Ends Well?

Genomics 101

Genomics 101

FIBER OPTICS

FIBER OPTICS YOU ROCK

YOU ROCK LIGHT FANTASTIC

LIGHT FANTASTIC FULL CIRCLE

FULL CIRCLE TOTALLY TWISTED

TOTALLY TWISTED STREET SMART

STREET SMART BRAISE THE ROOF

BRAISE THE ROOF ON THE ROAD AGAIN

ON THE ROAD AGAIN A LITTLE SNAP

A LITTLE SNAP GROOVY

GROOVY CAN DO

CAN DO BACK IN BLACK

BACK IN BLACK While diet, eating healthy fresh produce, sensible exercise and good habits enhance our bodies, how do we feed and enrich our soul? To this end, the love of pets, offspring and friends, volunteerism and openness to the new play a large role. Martha draws much of her inspiration not only from reflecting on her own life, but also from her positive relationship and experience with her mother as she aged. Her love and admiration is palpable in these pages.

While diet, eating healthy fresh produce, sensible exercise and good habits enhance our bodies, how do we feed and enrich our soul? To this end, the love of pets, offspring and friends, volunteerism and openness to the new play a large role. Martha draws much of her inspiration not only from reflecting on her own life, but also from her positive relationship and experience with her mother as she aged. Her love and admiration is palpable in these pages.

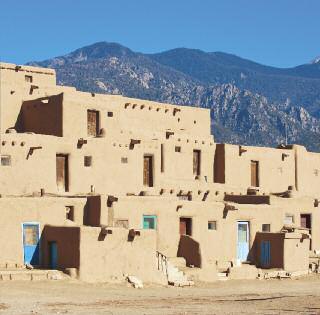

BLUE LAKE • NEW MEXICO

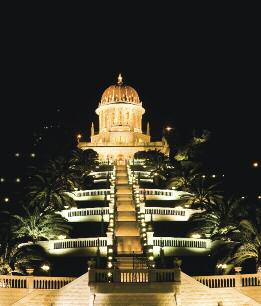

BLUE LAKE • NEW MEXICO BAHA’I HANGING GARDENS • ISRAEL

BAHA’I HANGING GARDENS • ISRAEL ULURU • AUSTRALIA

ULURU • AUSTRALIA To those who hold Ayers Rock sacred it is known as Uluru. The beliefs that are ascribed to Uluru are integral to what is called The Dreaming—which holds that the spirits of human ancestors came to earth to create the land and all its features. Once their work was completed, those same spirits remained and changed from human form into stars, sunsets, rocks, rivers, shrubs, trees, stones and animals. As such they are ever-present. For Aboriginal believers, The Dreaming is never-ending, linking the past and the present, the people and the land; all that is sacred is in the land.

To those who hold Ayers Rock sacred it is known as Uluru. The beliefs that are ascribed to Uluru are integral to what is called The Dreaming—which holds that the spirits of human ancestors came to earth to create the land and all its features. Once their work was completed, those same spirits remained and changed from human form into stars, sunsets, rocks, rivers, shrubs, trees, stones and animals. As such they are ever-present. For Aboriginal believers, The Dreaming is never-ending, linking the past and the present, the people and the land; all that is sacred is in the land. NEWGRANGE • IRELAND

NEWGRANGE • IRELAND

desirable destinations in all of New Jersey; visually arresting, creatively energetic, spiritually satisfying. He convinces 20-something me.

desirable destinations in all of New Jersey; visually arresting, creatively energetic, spiritually satisfying. He convinces 20-something me. Chef Mark Miller fell into step with the distinctive Hamilton style several years ago when he took charge of the kitchen. The seamless transition means the romantic rusticity of the dining rooms can be appreciated without reservation. There’s the high-ceilinged, banqueted Gallery Room, along the canal; the twinkling-lights Garden Room; the private-for-a-party, mural-filled, post-and-beamed Delaware Room, warmed in winter by a Franklin fireplace; the airy and open Grill Room; and the intimate Bishops Room, with a framed mirror on the ceiling and angels painted on bead-board walls. In milder months, outdoor seating along the canal is the prime place to perch at Hamilton’s Grill Room, sipping wines you tote along and reveling in Jim Hamilton’s dreams come true…and food true to Hamilton’s roots as a home cook who believes in the integrity of basic Mediterranean food and using ingredients locally sourced.

Chef Mark Miller fell into step with the distinctive Hamilton style several years ago when he took charge of the kitchen. The seamless transition means the romantic rusticity of the dining rooms can be appreciated without reservation. There’s the high-ceilinged, banqueted Gallery Room, along the canal; the twinkling-lights Garden Room; the private-for-a-party, mural-filled, post-and-beamed Delaware Room, warmed in winter by a Franklin fireplace; the airy and open Grill Room; and the intimate Bishops Room, with a framed mirror on the ceiling and angels painted on bead-board walls. In milder months, outdoor seating along the canal is the prime place to perch at Hamilton’s Grill Room, sipping wines you tote along and reveling in Jim Hamilton’s dreams come true…and food true to Hamilton’s roots as a home cook who believes in the integrity of basic Mediterranean food and using ingredients locally sourced. Cooking…By Design

Cooking…By Design

The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Asian Burger

The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Asian Burger  Paragon Tap & Table • Lobster Ravioli with Chipotle Shrimp Sauce

Paragon Tap & Table • Lobster Ravioli with Chipotle Shrimp Sauce  A Toute Heure/100 Steps Supper Club & Raw Bar

A Toute Heure/100 Steps Supper Club & Raw Bar The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Tex-Mex Crunch Burger

The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Tex-Mex Crunch Burger  The Black Horse Tavern & Pub • Summer Smoked Pork Chop

The Black Horse Tavern & Pub • Summer Smoked Pork Chop  Piattino Neighborhood Bistro • Amalfi Seafood Pasta

Piattino Neighborhood Bistro • Amalfi Seafood Pasta  The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Jersey “ Wake Up” Call

The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Jersey “ Wake Up” Call  George and Martha’s American Grille • Sliced Hanger Steak

George and Martha’s American Grille • Sliced Hanger Steak  The Office Tavern Grill • Slow Roasted Chicken Tacos

The Office Tavern Grill • Slow Roasted Chicken Tacos Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Pan Seared Scallops

Arirang Hibachi Steakhouse • Pan Seared Scallops  Daimatsu • Wild Caught Sushi

Daimatsu • Wild Caught Sushi Publick House • Grilled Swordfish

Publick House • Grilled Swordfish  Morris Tap & Grill • Smoked Scallops with Corn Risotto

Morris Tap & Grill • Smoked Scallops with Corn Risotto Thai Amarin • Gang Phed Ped Yang

Thai Amarin • Gang Phed Ped Yang Café Z • Cappellini Arugula del Gamberoni

Café Z • Cappellini Arugula del Gamberoni  Chestnut Chateau • Gifts from the Sea

Chestnut Chateau • Gifts from the Sea Mario’s Tutto Bene • Vinegar Pork Chops

Mario’s Tutto Bene • Vinegar Pork Chops  Rio Rodizio • Brazilian Meats

Rio Rodizio • Brazilian Meats The Manor • Seared Atlantic Salmon

The Manor • Seared Atlantic Salmon The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Pacific Island Ahi Tuna Burger

The Office Beer Bar & Grill • Pacific Island Ahi Tuna Burger

Meg Daniels will continue solving crimes, Kelly expects. However, there are plans in the works for new characters. Devising the complex plots in her novels almost comes naturally to Kelly now, but it’s her characters that make each book special. “If I were only concerned with plot, I’d be publishing books a lot more quickly,” she says. “The characters always end up taking on a life of their own…and if I can’t ‘hear’ them in m

Meg Daniels will continue solving crimes, Kelly expects. However, there are plans in the works for new characters. Devising the complex plots in her novels almost comes naturally to Kelly now, but it’s her characters that make each book special. “If I were only concerned with plot, I’d be publishing books a lot more quickly,” she says. “The characters always end up taking on a life of their own…and if I can’t ‘hear’ them in m

American Pastoral

American Pastoral The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao Bruce

Bruce The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation Independence Day

Independence Day Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass New Jersey: A History of the Garden State

New Jersey: A History of the Garden State The North Side: African Americans and the Creation of Atlantic City

The North Side: African Americans and the Creation of Atlantic City  Paterson

Paterson This Side of Paradise

This Side of Paradise Toy Bulldog: The Fighting Life and Times of Mickey Walker

Toy Bulldog: The Fighting Life and Times of Mickey Walker

SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A YOUNG ADULT BEST-SELLER…

SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A YOUNG ADULT BEST-SELLER… DIRTY DOZEN

DIRTY DOZEN